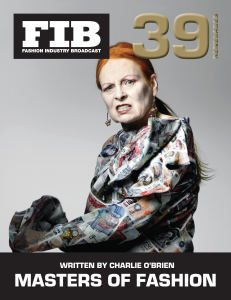

In honour of our upcoming “Masters of Fashion: Renegades” edition, we at Fashion Industry Broadcast are giving you a taste each week of the gifted and often troubled individuals that choose to forge their own paths in the fashion world. This week is Vivienne Westwood, the counter-revolutionary and design icon who redefined fashion as high art with a conscience. Enjoy!

Punk. Dame. Designer. Rebel. Millionaire. Mother. Radical. All words one could use to describe Vivienne Westwood, perhaps the most influential British designer the world has ever seen. In an industry predominantly known for showcasing beauty, Westwood used to talent to advocate for higher causes – be it art, history or her passion for social justice. She redefined what being a designer could represent, inspiring a wave of others dedicated to using fashion as a means of confronting the status quo.

Vivienne Isabelle Swire was born in 1941, in the village of Tintwistle, Derbyshire. Her parents, Gordon and Dora, had met two years previously, at the onset of the Second World War. She was the eldest of three children in a family far removed from the English elite: Gordon worked as a storekeeper in an aircraft factory while Dora helped make ends meet by working in a local cotton mill.

She was always close with her family – her parents in particular, who imbued Westwood with a confidence and self-sufficiency rare for a woman of her generation. She would often be found wandering the countryside of Derbyshire, climbing trees and jumping streams in a manner most parents would disapprove of for a young girl.

“I liked being me, and I happened to be a girl. I wanted to be a hero and saw no reason why a girl couldn’t be one.”

Her heroism developed through her schooling years. Despite her enjoyment of school – she was a proficient reader and held a fascination with knowledge, even from an early age – Westwood saw herself as “a kind of champion” for the marginalised, standing up to authority figures at the behest of those who could not, or would not, stand up for themselves.

On numerous occasions in class she took the blame for actions that were not hers, testing the boundaries of authority figures and finding fulfillment in the “glamour of the self-righteous.”

Despite her love of education, Westwood’s parents were wary of the abstract knowledge that came from books and preferred her to learn the more practical knowledge of tradecraft. Gordon and Dora hailed from generations of grocers and shoemakers and both were deftly skilled with their hands. Dora, in particular, was a gifted seamstress who insisted on sewing all the clothes for her children.

When her parents moved to Harrow, London in 1958 to take over the running of a post office, Westwood – 17 at the time – enrolled in the nearby Harrow School of Art to study silver-smithing; but after a single semester she opted to drop out of the school for good. It was one of the few times in her life her infallible sense of confidence failed her. “I didn’t know how a working-class girl like me could possibly make a living in the art world,” she said years later.

Instead, Westwood took a job a a factory while studying at a teacher-training college, eventually becoming a fully certified primary school teacher. By 1963 her life was seemingly on a track towards the inconsequential. Vivienne had married Derek Westwood – a handsome mod who ran dance halls and aspired to become an airline pilot – the previous year; by 1963 she had given birth to her first son, Ben.

Derek was a dedicated father and a supportive husband. But Vivienne was anxious in the role of matriarch, concerned her life of adventure and knowledge was being abruptly cut short: “I wasn’t happy. I wasn’t content looking after my child. I needed to know more of the world.”

Vivienne left Derek a few months after the birth of Ben and was back to living with her parents above the latest in a series of post office they now ran, continuing to work as a teacher and selling handmade jewellery on the side.

Everything changed for Westwood in 1965. Her brother was studying at a local art school and invite friends back to the post office. One in particular, a pale redhead by the name of Malcolm McLaren, was particularly drawn to Vivienne and offered to help craft her jewellery.

“I was very impressed by his designs,” Westwood recalled. “They were very mod.” According to Westwood, McLaren was relentless in his pursuit of her, and she eventually succumbed to his advances and decided to sleep with the 19-year-old. She was 25 at the time.

A few weeks later, Westwood was pregnant with her second child. McLaren did not react well. He was a chaotic figure, born into supreme family dysfunction. He held no interest in being a father and secured the money for Vivienne to have an abortion. But on the way to the clinic she had a change of heart, spending the money on a cashmere twinset instead.

Her second son, Joseph Corré, was born in November of 1967. His surname was dedicated to McLaren’s grandmother Rose Corré: the woman who, only months beforehand, had provided the money for Westwood to have an abortion.

True to his word, McLaren was utterly disinterested in fatherhood. He showed up to the hospital six days after the birth of his child to visit Westwood; and in the ensuing months and years, continuously reminded her and anyone who would listen how unattached to his child he was.

Their relationship was acrimonious at the best of times. In recent years Westwood has stated she never wanted to be with McLaren but found herself overwhelmed by his obsession for her; an obsession that often manifested in emotionally and sometimes physically abusive behaviour.

“He behaved incredibly cruelly. Professionally, personally, in every way,” Westwood revealed in her memoir. “It was simpler to give in; to give way to the tears so he would stop. Real tears have never come back for me. I haven’t cried properly since.”

But Westwood was obsessed in her own way: fascinated by his unique perspective on the arts and his flagrant disregard of authority: “I latched onto Malcolm as somebody who opened doors for me. I mean he seemed to know everything I needed at the time.” McLaren was instrumental in altering her look from “dolly bird into a chic, confident woman.”

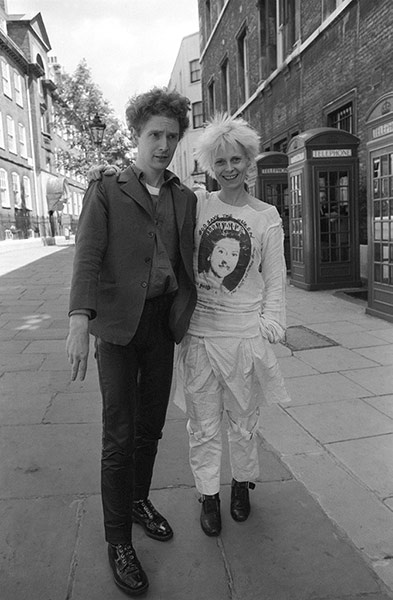

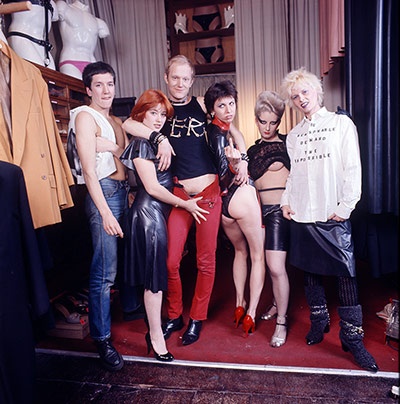

He would dress Westwood like a prostitute – schoolgirl uniforms with red latex tights, for example – in an effort to erode her confidence. Yet her radical new look only emboldened her independent streak and renewed her passion for design. Together the tumultuous couple opened a boutique in 1971 named Let It Rock, and after flirting with several styles – rockabilly, mod, and greaser – McLaren stumbled across the punk movement during a trip to New York City.

Inspired by the punk ethos and its anti-authoritarian stance, McLaren decided to import the subculture to the United Kingdom. He and Westwood changed the boutique name to SEX and began their aggressive expansion. While McLaren recruited a band to model their attire, most of the fashion we now associate with punk – from spiked dog collars to clothes strung together with safety pins – was designed and constructed by Westwood in the couple’s South London apartment.

“I particularly loved my SEX look: my rubber stockings and the T-shirt with pornographic images and my stilettos and spiky hair… I stopped the traffic in my rubber negligée.”

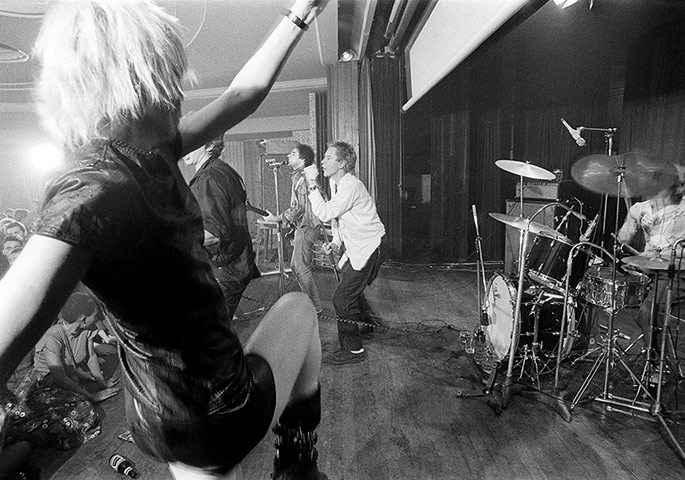

McLaren was a superlative promoter, who used the success of his band The Sex Pistols to take their boutique to new heights of success. But it was Westwood who pushed the boundaries of punk fashion and what it could represent, incorporating politically-charged messages and social taboos as a means of shocking the establishment and disrupting the status quo.

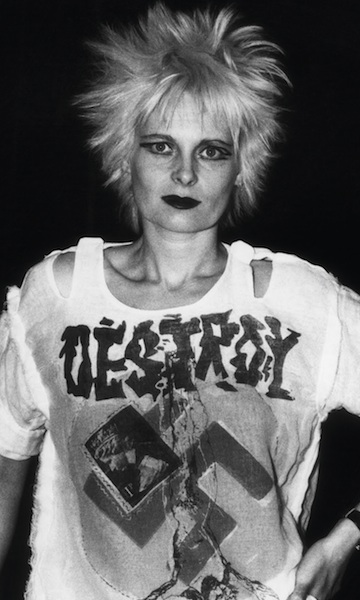

One such instance is the infamous “DESTROY” shirt, emblazoned with an enormous swastika across the front. Even now, the garment remains highly controversial – but Westwood has no regret about her design choices: “we were just saying to the older generation, ‘We don’t accept your values or your taboos, and you’re all fascists.’”

Punk had infected Britain by 1977. The Sex Pistols were the biggest band in the country, and off the back of their success the boutique – now labeled Seditionaries – had become the epicentre of the movement. Thousands of disenfranchised youths across the country were wearing designs either created or inspired by Westwood. But once more in her life, Westwood was discontent – for a number of reasons.

Her dedication to the punk movement had come at a cost. Westwood has acknowledged she was an unfit mother at the time, stating “I neglected my children because I had to do certain things, which meant that I couldn’t be there for them – in order to do ‘fashion’, because, at the time, I thought fashion was a kind of crusade.”

To make matters worse, McLaren refused to share the success of bringing punk to the mainstream, referring to Vivienne only as his “seamstress” and denying her the design credit she deserved.

But her true dissatisfaction with punk came in ideology. For McLaren, punk was a sustained disruption of order: chaos for the pure sake of chaos. But for Westwood, punk was social change through radical action, a means to “confront the rotten status quo through the way I dressed and dressed others.”

“I was messianic about punk, seeing if one could put a spoke in the system in some way.”

Under the guidance of McLaren, the punk movement had become a circus of hedonism and aimless rebellion – not the revolutionary battle cry Westwood was hoping for: “when I turned round, on the barricades, there was no one there. That was how it felt. They were just still pogoing. So I lost interest.”

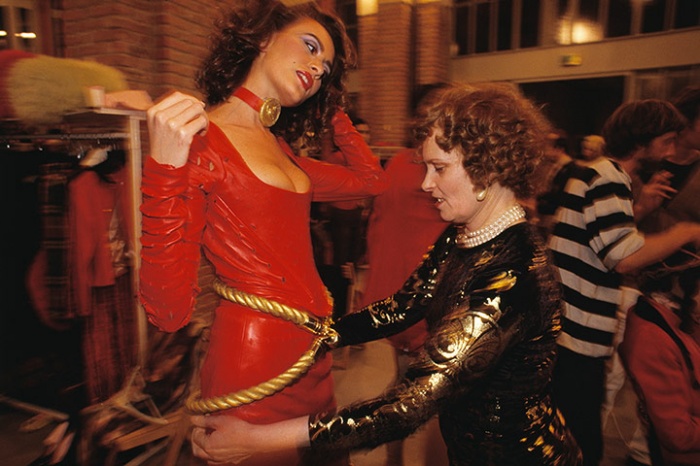

By the early 1980s Vivienne had tired of the punk ethos and yearned to push her sense of design to new places. She and McLaren remodeled the boutique one final time, naming it World’s End, and in 1981 the pair launched their first catwalk collection, Pirate.

The collection – consisting of clothes influenced by the golden age of buccaneers and highwaymen – was an instant hit with the fashion world. Westwood was no longer rattling the establishment from the outside: she was actively working from within mainstream culture to influence change.

McLaren and Westwood followed Pirates with a number of collections she later grouped under the banner “new romantic.”

Each collection was profoundly different from the next as Westwood flexed her creative muscle: Savages (SS 1982) was influenced by Native American patterning with a twist of Foreign Legion; Nostalgia of Mud (AW 1982) embraced enormous tattered shirts and sheepskin jackets saturated in muddy colours; Punkature (SS 1983) drew inspiration from Ridley Scott’s dystopian sci-fi classic Blade Runner while Witches (AW 1983) conjured the “magical, esoteric sign language” of New York graffiti artist Keith Haring.

Witches proved to be the final collaboration between McLaren and Westwood; after ten tormented years, the couple dissolved their relationship.

Free from her previous constraints, Westwood began to find her true voice as a designer. She began to draw more inspiration from the annals of history, sourcing ideas from the literary and cultural expertise of Gary Ness, a former painter with whom Westwood had developed a close bond. Westwood saw a fellow ideological iconoclast in Ness: someone she could rail against the barricades with, who could help her say exactly what she wanted to through fashion.

One of Westwood’s first major accomplishments as a solo designer was the “mini-crini” of 1985. Combining the tutu with an abbreviated form of the Victorian crinoline, the mini-crini was a simultaneous rejection of the masculine shoulder pads popular at the time and a cultural homage to the classic Russian ballet Pretushka.

A random encounter with a young woman in London proved the inspiration for one of Westwood’s most iconic collections: the Harris Tweed, AW 1987.

“My whole idea for this collection was stolen from a little girl I saw on the tube one day. She couldn’t have been more than 14. She had a little plaited bun, a Harris Tweed jacket and a bag with a pair of ballet shoes in it. She looked so cool and composed standing there.”

The collection, partially inspired by the British Royal Family and notable for its use of 18th century corsets, was a runaway success and cemented her position as one of the most influential designers in the world. Westwood continued to find sartorial inspiration by delving into the catacombs of cultural history: Pagan I (SS 1988) for example, was an eccentric mix of traditionally British fabrics and pagan design elements, with patterns procured from pornographic images of Ancient Greece.

Time Machine, AW 1988-89, was of similar eclectic design. Named after the eponymous H.G. Wells novel, the collection used tweed to construct suits modeled after medieval armour. And Cut and Slash, SS 1991, took its layered textile design from a 16th century French tradition, in which they would cut and prick fabric in such a way it would last hundreds of years.

By the mid-90s, Vivienne Westwood was one of the most established and exciting names in fashion. Her fascination with the cultural histories of the English and French saw her create some of her most inspired designs:

“On the English side we have tailoring and an easy charm, on the French side that solidity of design and proportion that comes from never being satisfied because something can always be done to make it better, more refined.”

Some of the designs were almost unwearable by conventional standards. The SS 1996 collection Les Femmes ne Connaissent pas toute leur Coquetterie (“women do not understand the full extent of their coquettishness”), for instance, incorporated the use of body extensions – padded busts and hips – along with bustles created by metal cages that tied together to create an exceptionally exaggerated hourglass silhouette.

Westwood has little time for convention, and her designs often run contrary to the fashions at the time. Her Dressing Up collection, AW 1992-93, was an example of exactly that: the elaborate use of layers and high-cost fabrics at a time when economic downturn saw the majority of designers moving in the opposite direction.

As fashion grew increasingly infatuated with minimalism, Westwood remained as intricate as ever: the 2000s saw her move away from historical influences as she turned inward and sourced inspiration from the nature of the fabric itself – treating it as a living, evolving mass.

Despite her anarchistic punk beginnings, it was Gary Ness, her cultural guru, who first saw the potential of Vivienne Westwood. She was not a revolutionary but a counter-revolutionary: a woman willing to reject the bland populism of modern fashion in favour of a much higher ideal – a return to the realms of high art, a defiant exploration of timeless culture in the age of disposable postmodernist ideals.

Paradoxically, by rejecting trends and forging her own path, Westwood became a trendsetter of her very own. Without her pioneering work in fusing fashion with history, John Galliano may never have drawn upon the French Revolution for his early inspiration; likewise, renegade designers such as Alexander McQueen, Marc Jacobs and Jayne Pierson owe a huge debt to Westwood for pushing the boundaries of what fashion can represent.

One of the secrets to Westwood’s continued success as a designer comes in the form of husband Andreas Kronthaler, her loyal design partner and perhaps her biggest advocate as an artist. After a decade of avoiding men thanks to the difficulties she faced with McLaren, Vivienne met Andreas while teaching at the Vienna Academy of Applied Arts.

Vivienne, then 48, was impressed with Andreas’ designs and invited the 23-year-old to London to work with her. He shared her vision of fashion-as-art and held a more supportive, collaborative disposition than McLaren could have ever imagined. They quickly became an item and married in 1993. Together the couple oversaw the stratospheric rise of Vivienne Westwood Ltd, which now boasts 63 outlets worldwide and has instilled Vivienne with an estimated net worth of $185 million.

Yet over the past decade Vivienne has become less involved with the day-to-day planning of her fashion empire. She prefers to use her fame and wealth to advocate numerous social causes, often instilling her personal and political beliefs within her collections – such as when she set a 2011 campaign against the backdrop of a Nairobi slum to advocate her partnership with the Ethical Fashion Africa Programme, or drew attention to the persecution of Wikileaks founder Julian Assange by imprinting his name and image on t-shirt designs in 2013.

But by far, her greatest cause is climate change. The longtime Labour Party supporter, who swapped to the Conservative Party in 2007 due to human rights issues is now the largest donator to the Green Party of England and Wales because she is “traumatised by the problem of climate change.”

Westwood started Active Resistance in 2005, a project designed to stimulate engagement in humanitarian and environmental issues, and many of her collections have since reflected that theme, including 50+, a 2009 collection that cultured inspiration from the predicted temperature of the Earth by 2050 if climate change is left unchallenged.

Her crusade against climate change has found her squarely at odds with the industry that generated her fame. She is a staunch opponent of the wastefulness of fast fashion and encourages people to “not buy clothes” – declaring that people should commit to a select number of outstanding pieces rather than an expansive, interchangeable wardrobe.

Such is the air of contradiction surrounding Westwood. She decries the fashion industry as she profits from it, bemoaning the influence of advertising while simultaneously creating celebrated campaigns with some of the highest-profile photographers in the world. The multimillionaire rails against an established order she has long been a part of: socialising with billionaires such as Richard Branson in private jets and appearing on talk shows in ludicrously expensive and elaborate silk dresses to complain about the wasteful state of the bourgeois.

Yet somehow it doesn’t feel hypocritical. Westwood believes everything she says with a passion and fervor all-too-rare in our detached modern society; managing to hold contradictory sentiments and convey them in the honest, confident manner that has come naturally to her since she was a child.

“What I’m doing now, it still is punk — it’s still about shouting about injustice and making people think, even if it’s uncomfortable. I’ll always be a punk in that sense.”

Long after the chaos-inducing punks have burned out to their ineffectual ends, Vivienne Westwood is still standing strong. She made a conscious decision to move from the sneering outcasts and become a member of the social elite, using her esteem and stature to continue challenging the status quo and compel others to rail on the barricades of social change with her. She is no longer putting a spoke in the system; she is the spoke in the system – earning the mantle of Britain’s most inspiration designer along the way.

And for those who consider Westwood too far removed from the heady days of punk, consider this: when the woman who dressed the band famous for their song God Save the Queen received her Damehood in 2006, she did so in a beautifully tailored dress – and no knickers.

Flashing the Queen: what’s more punk than that?