Peruvian fashion photographer Rodrigo Diaz of Estudio Diaz recently caused outrage when he shot a terrorism-inspired photoshoot.

The shoot was inspired by the aftermath of the actions of the ‘Shining Path’ Marxist rebels who sparked a civil war in Peru in the 1980s and 1990s that claimed 69,000 lives. The Andean nation’s official Truth and Reconciliation Report found the Shining Path responsible for 31,333 of those deaths.

Diaz posted the photo series on Facebook with a header reading, ‘I don’t forgive, nor forget.’

According to the Truth and Reconciliation Report, atrocities committed by the Shining Path include car bombings, murdering babies with axes and ‘dynamiting’ corpses. The victims of the Shining were often poor, Indigenous people living in remote rural areas in Peru, far from accessible aid.

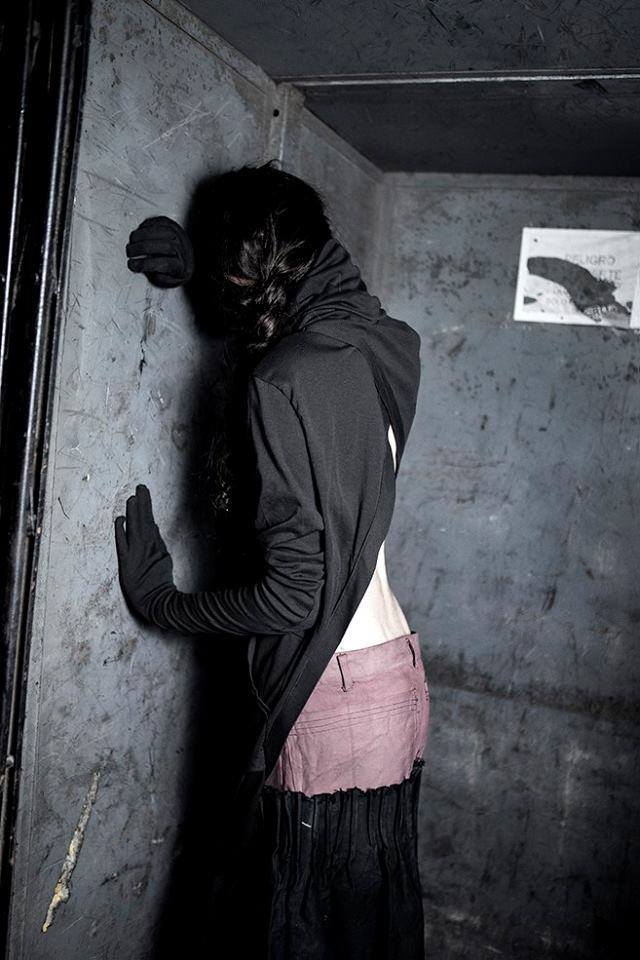

Diaz thanked the stylist, fashion designer and model in his public Facebook post announcing the photo shoot, in which the model appears gaunt and her expression is lifeless and traumatised.

The online backlash was instant and huge. One commenter shared a link to the database of victims and incidents prepared by Peru’s Place of Memory, Tolerance and Social Inclusion with the comment:

“That way you can properly inform yourself before trivializing and banalizing such a painful and traumatic experience for our country. Regrettably, your project has been, to say the least, an insult to the tens of thousands of victims of the two decades of violence and the very historical memory of Peru, which is costing so much effort to preserve.”

Diaz deleted his Facebook post announcing the photo series and wrote an extensive apology on the site. He said that some of the offence might have been avoided if he had introduced the shoot properly, with the clothing line’s name – Scars (Cicatrices) – instead of saying that it was “inspired by terrorism”.

This isn’t the first time in recent months that a fashion photography shoot has caused widespread outrage. In October, Hungarian photographer Norbert Baksa’s refugee-inspired shoot entitled Der Migrant invoked online wrath after depicting a model posing glamorously beside a barbed-wire fence on the Hungary-Croatia border. She wore luxurious scarves and posed with a Chanel-branded smartphone in some shots, while other photos showed her struggling with and being held by a police officer.

Unlike Diaz, Baksa issued no apology for his photoshoot. He posted a lengthy explanation on his website:

“This is exactly what we wanted to picture: you see a suffering woman, who is also beautiful and, despite her situation, has some high quality pieces of outfit and a smartphone.

“The shooting is not intended to glamorise this clearly bad situation…Artists around the world regularly attract the public’s attention to current problems through ‘shocking’ installations and pictures.

“To people who said I am stupid, I can only say they should examine the problem from different angles, all the more that they do not live in Hungary, so they do not experience it firsthand. It is very difficult to understand from the news coverage whether these people are indeed refugees or something else.”

Baksa also issued a press release regarding Der Migrant and his experience of the refugee crisis is Hungary.

“We chose the title to be in German for several reasons. First and foremost, Germany is the leading power of the European Union and most migrants wish to live in Germany. Choosing the masculine form while picturing a woman also points out the fact that the issue of migrants can be and is viewed in different manners…Some will see refugee families with small children fleeing for their lives, while others only see masses of riotous migrants or even terrorists attacking police and representing a threat on our societies.

“My Hungarian background influenced the photos in that I live in Hungary. I see the issue on a daily basis… I met people from both sides and realised how differently they see the issue.”

Whether one agrees with Baksa or not, it’s clear that war and the refugee crisis are complex issues.

Fashion photography is art. Art has always responded to current events, it’s always evoked criticism, it’s always pushed boundaries and it’s always had an impact. But it’s important to understand what the impact is. Diaz’s shoot and Baksa’s shoot both glamorise situations that are deep sources of trauma for countless people. It’s fair to suggest that this sort of trivialisation is a form of distancing – a way to throw war victims back into the position of the spectacle-like ‘other’ when they desperately need their voices to be heard.

In defence of Diaz and Baksa, it could be argued that sometimes making people angry is the point of art. Anger is a transitive emotion; it motivates people to take action. If you can get angry at a fashion photographer for depicting a terrorism victim or refugee in an insensitive way, why not get angry about the circumstances that led to their situation in the first place? Sometimes, raising awareness isn’t enough – sometimes a catalyst is needed to make people realise how much they care.

However, another strong argument against terrorism and war-related crises being illustrated in fashion photography is that fashion photography usually has a commercial intent. We can reasonably ask, was Baksa’s shoot really intended to represent a complex issue or was it intended to advertise Chanel? Did Diaz care at all about the pain and loss felt by the victims of the Shining Path that his shoot was inspired by, or was he simply using the issue to attract attention to the clothing line, Scars? If it’s the latter, then his objective was definitely met.

Conversely, there are photographers who use their art to spread compassionate awareness and amplify the voices of those who call for help. Anyone familiar with Brandon Stanton’s Humans of New York knows the power of photojournalism to break down prejudices and connect people across international borders. And consider these photographs by Turkish photographer Metin Demiralay, which also show beautiful girls by barbed-wire fences, but in a way that evokes empathy and complex emotions.

We can sense the models’ longing and almost identify with their situation, even though in daily life it may seem worlds away from our own. These works are genuinely powerful. Their beauty and sadness resonate with us. They have a deeper impact than the knee-jerk reaction that we get from Diaz’s and Baksa’s sensationalistic images.

Comparing the styles in which these different photographers address similar issues, it’s clear that execution is key. Current affairs are not something that photographers should shy away from, but war is a topic that can only be addressed tastefully when handled with integrity and care. The word ‘offensive’ is thrown around so much that it’s understandable why an artist would scoff at it. But if a photographer can’t visually articulate the message that they’re trying to convey, it’s not just a reflection of their character – it’s a reflection of their skill.

Fashion photography is a fledgling art form with ties to both the commercial world and the world of creative exploration – and as such, it can be a messy area. It is clearly a medium that can bring attention to war and the struggles of war victims. But is it the right medium? Most responses to the works of Diaz and Baksa would indicate that it’s not.