The countercultural artistic phenomenon of the 1960s and 1970s America was a politically and socially driven collaboration of artists speaking back to the embedded authoritarian control of their environments. It was a visual way of motivating, highlighting and expressing and it was a means of striving for change.

Flash forward almost fifty years and it seems in a multifaceted new media landscape – in the age of Donald Trump, social media and ‘fake news’ – that there are more voices, more ways of interpreting and more opportunities for culture to protest its environment. We take a look at how these kind of art forms still being created…

In 1960s and 1970s America, in a time imbued with injustice and violence, countercultural communities were creating politically and socially driven acts of art-making on a number of platforms. They captured a rupturing of social energy, and they facilitated a sphere in which they could create works of protest that could be widely distributed and publicised. Indeed, they recognised the power of the visual and the literary to facilitate change.

With this in mind, I’ve started to consider two things: that times of tension and devastation always contribute to the construction of meaningful art; and that in these contexts of unrest, artists’ disassociation with institutions of power allow them to gain wider social control. Take a look at artists like Martha Rosler and Ad Reinhardt, for example, and the student and the New York art protest of 1970 that fought against Vietnam war conscription. It’s clear that artists and artwork have the ability to create a space of community and protest.

The 1960s saw the Vietnam War, conscription and a definitive divide between the gendered domestic and public spheres. Artist Martha Rosler emphasised a disassociation between the American homeland and the country’s conflict in Vietnam. The directive, violent and generally irrelevant conscription of young American men into the war saw an outcry of embittered individuals in subcultural artistic communities. It was one of the social and political injustices that saw these countercultural artists begin to use their creative voices and practices to attempt to effect change.

Rosler’s collage series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home (1967-72) saw a powerful new visual representation of images of the increased mobilisation of American troops in the Vietnam War -repeatedly seen but largely unacknowledged. At this time, violence was central to everyday life, but it was confined and restricted in the frames of home television screens. Rosler looked to deconstruct this American disassociation with Vietnam and its people in what she called a ‘living room war’. She wanted to remove the polarisation of place that deemed American’s unresponsive to the violence overseas. Her multimedia collage practice, previously used as protests against women’s representation in the media, was used again to project Rosler’s anti-war ideals.

The idea for these images emerged when she saw horrific photographs of the Vietnam War next to ads for a couch company in a lifestyle magazine. She scrutinised these absurd combinations of imagery through a reorganisation of existing mass media images. In the placement of these images in the domestic home, she constructed a relational environment for reflection. Christopher Lasch once suggested that the ‘home is a haven in a heartless world.’ This realm of constructed security was considered by Rosler instead, perhaps as a place of concealment, with an artificial dismissal of the cruelty of the outside world. The works also stage the viewer as an active participant in this domestic space – the images seemed to say ‘this is your world and your understanding of it.’

Roller has said of these works, ‘It wasn’t about contrasting two realities, but two world views: our ideal self and this other thing which was the unacceptable realities of another place.’ By combining these realistic opposing pop culture and current affair symbols, all of them become signifiers of what Rosler sees as a dissociation with global catastrophe. These dark discourses were the muses for such countercultural expressions, expressions that made a lasting impact because as Roszak said,

’ [they] strike beyond ideology… seeking to transform our deepest sense of the self, the other, the environment.’

Like Rosler, Ad Reinhardt in his postcard artworks, visualises the widespread ignorance of Americans toward a series of political and social issues: the Vietnam war and racial discrimination, for example. He, however, forwards his message to the government as a physical postage. His visual/poetry hybrid work ‘No War’ applies the language and projection of his art writing background. By warping and reshaping the compositional elements of worded poetry, he forms simultaneously visual and rhetorical protests. While Rosler uses the mass-media fragments of popular culture imagery in her ‘Home beautiful’ collection, Reinhardt uses the mass media processes of widespread distribution: the printing and selling of the visual. Though the structural elements of this piece seem synonymous with high art in its poetic form, they also mirror everyday practices through the materiality of the transmission postcard.

Though, while Rosler’s images are simply publicly distributed, Reinhardt’s also mean to be sent directly to government as acts of defiance. Indeed, perhaps the reason the postcard’s lettering is so unambiguous is because this shorthand style provides no room for argument. Each command is imperative – ‘No War’, ‘No Napalm’ for instance, so that while Reindhardt’s intended audience is members of institutional hierarchy, his clear and simple political messages further resonate with American society. ‘No War’ certainly facilitates a sense of immediacy, its truncated poetry-like repetition gradually lengthens from specific comments on Vietnam, ‘No Napalm’ and ‘No War’ to expanding inherent American normalcies – ‘No Escalation’, ‘No Poverty’, ’No Injustice’. It is, in its content and representation, a work of uninterrupted defiance against government policy and socially undermined discrimination.

Like Rosler, Reinhardt engineers social semiotics to divert from existing representations of America. By using mass media, common practices of the everyday, the artists disseminate somewhat temporal and movable images. They are aware that like mass media, their works will not be represented permanently within the gallery walls, but it is this presentation that gives them their countercultural and protest validity.

Reinhardt’s postcard overleaf questions the power of art making to facilitate change. When Reinhardt writes ‘No art in war’ and ‘No art about war’, or ‘No art as war’, he critiques the rising absurd relationship of aesthetics with political resistance. In fact, he paradoxically questions the power of his art forms: critiquing protest art through the very medium of protest art. His public comments on American artists’ roles in these times of tension may strengthen this view. He states ‘I think an artist should participate in any protest against the war… first… as a human being’. The disparity doesn’t minimise the power of Ad Reinhardt’s postcards, but further contextualises the tension and confusion of this era and time in which countercultural methodologies saw artists actively searching for the ‘right’ way to contribute to change; an ideal that created a misidentification of the artist and led to the rise of this community. This drive alone proves the works should be considered ‘meaningful’.They share parallels with the New York Protest of 1970. The visual and linguistic messages on billboards construct an even deeper revolutionary aesthetic when held by the creators of the art inside the galleries’ walls.

Revolutionary artworks of 1960s and 1970s America formed prominence as effective, countercultural expression because they worked extensively outside of institution. The works, in a way, became aesthetic, revolutionary pieces of journalism as their intent was fuelled by hybrid forms of activism and art making. Though they were detached from institution and mass media, they still manipulated these mainstream mentalities. Their in-between state as both culture and politics gave them affirmation as platforms for disseminating awareness of social and political injustices.

The institutions that artists worked against were not only government legislation, but extensively the major artistic museums of the time. Many were concerned, particularly Ad Reinhardt, that museums were representing themselves as modernity; when in fact exhibitions so often recognised classic or canonical works, or were manufactured to repress the tensions and violence of the period rather than allowing creatives to express their dismay on an array of issues. The distinctive ‘us versus them’ mentality between the artists and institution as well as the ‘west of centre’ countercultural spaces and ideals created by these artists forged collective community power. Artists in all countercultural avenues seemed to repeatedly suggest that these issues involved everyone. Rosler used perspective as a tool to portray this interaction, by always placing the viewer in the centre of the domestic spaces she constructed.

In constructing the normality and ‘safety’ of a domestic space she made her works relatable and thus images of contemplation. Reinhardt used the everyday postcard as medium while he used coherent linguistic demands as content to ensure all were privy to his messages. The 1970 New York Art Strike involved all by working to disrupt the cultural actions of the city. With their attempt to close cultural institutional spaces they took control of the objects they were responsible for creating. They worked the environment they were the centre of to suit their means of protest.

Audre Lorde believed that ‘The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house’– a phrase that suggests external protest is the best means for gaining social influence. It is this mentality that mirrors the revolution of this period as being based on a direct and absolute break from the mainstream. These artists not only removed themselves from the structural norms of museums and galleries, but they also constructed their own ‘tools’ to, in a way, disembowel the centre of what these institutions withheld. They recognised ‘the museums… as their…canvases’ so were capable of placing limitations on these institutions to publicise the Vietnam War, racial police brutality and gender discriminations. This is what happened in the ‘New York Art Strike against Racism, sexism and violence’ (1970). This strike was a culmination of the tensions that had been rising since the early 1960s. The killing by police of students at Kent Street University culminated in the monolithic ‘sit in’ by artists on the steps of major museums and galleries, demanding that major galleries close on the 22nd of May in honour of the lives lost in the Vietnam War.

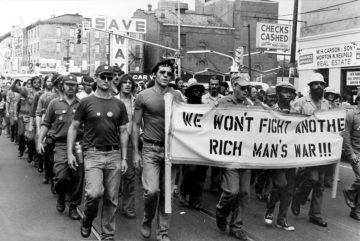

At least five hundred artists and critics repelled their individual academic and creative identities, and formed a boycott, that resulted in a high art cultural institution becoming a site of revolutionary protest. This saw the closing of galleries such as the Whitney and the Guggenheim. MoMa’s refusal to close became a directive target for the community. The spacial occupation by artists of these particular institutions became particularly effective because it attached the artistic community as a whole to these social and political causes. With the involvement of collective artists associations like the Art Workers Coalition, a group involved in the New York Art Strike as well as a letter written to Picasso to request the removal of his Guernica from MoMa, emerged the conviction that a cohesive group, bound by the practices of creative forms could produce a forceful urge for peace. As well as this, for the dissemination of these protests, there lay an array of visual mass media production tools that provided avenues for these artistic representations. Like Reinhardt and Rosler, by using the truncated and inarguable phrases inscribed on banners and held by the artists themselves in front of these colossal institutions, the group made use of the visual nature of mass media and television screens.

Current countercultural artistic works can be found in the realms of social media and in the niche market of countercultural, indie or controversial magazines. They can be found in an array of social media based online communities, or in the experimental realms of film, television and visual art. Predominantly, as one would expect in the 21st century, counterculture protest appears more online than it does in any physical space. While protest is organised through social sites, the interplay between protest and art has plateaued. We may find it, instead, on the many walls and streets of our cities – with street art manipulating public environments to speak politically. But these are just as much an avenue for social commentary as they are for protest.

Works appear readily, often in America and in ‘the age of Trump.’ Artists find protest opportunities most commonly in the heated public sphere, where onlookers – ordinary people going about their day can be ruffled by a visual display of something not quite right with the world.

In 2016, artists Hank Willis Thomas and Eric Gottesman commissioned American artists to create political advertisements as the Hillary-Trump election approached. A billboard labelled ‘Make America Great Again’ shows an image of police brutality. A force of irony that was to be showcased on a local heavy traffic highway.

Rosler says of her works that she was ‘interested in a visual means of processing something that involved us visually.’ Her comment relates more broadly with all countercultural works of protest. It is clear that these artists used visual means to produce expressions of revolution. But it is also clear, that by adhering to the confines of their artistic communities and avoiding the recognitions and expectations of the mainstream, government and institution, 1960s and 1970s countercultural artists produced not just aesthetic, complex and unique works of art but pieces fused with social and political intentions for change. Its the kind of public and political platform that, in 2017, we probably should be making more use of.

Do you have a favourite countercultural artist or artistic medium? We want to hear what you think.