Fashion Industry Broadcast and Style Planet TV is proud to present its new 11 part, hour long Film docuseries “Renegades”. As a teaser before the 11 films are released, we are revealing a post on THE BROADCAST each week for the next 11 weeks. This week the story is on Yohji Yamamoto.

Our Renegades refused to follow the laws of the ‘fashion rulebook’. The dreamers, the rebels, the auteurs, without whom popular culture would never have been quite as interesting. Even if you hold only the most casual interest in the world of fashion, it’s hard to deny the fascinating life stories of every one of our Renegades.

Featuring the lives and legends of:

- Vivienne Westwood

- Malcolm McLaren

- Hedi Slimane

- Rei Kawakubo

- Issey Miyake

- Kenzo Takada

- Yohji Yamamoto

- Alexander McQueen

- Jeremy Scott

- Rick Owens

- John Galliano

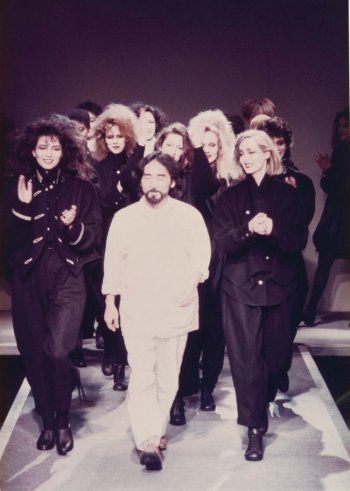

We present to you: YOHJI YAMAMOTO

“Every morning when I look at the mirror, I have found a very very old man who looks very tired, and I talk to myself are you still wanting to fight? This happens every day”.

Yohji Yamamoto is a man who understands the power of endurance. The product of a Japanese culture ravaged by war, the progressive designer has built his 50-some year career on perseverance and a refusal to bend to the will of tradition. From his initial struggles as an emerging designer to his incendiary debut on the world stage, all the way through to the near collapse of his company in the wake of the global financial crisis, Yamamoto has overcome every obstacle in his path – and always on his own terms.

Today, his eponymous brand offering both men’s and women’s clothing remains his most commercially successful venture alongside the popular sub- label Y’s and youth line Ground Y to its principal lines Pour Homme and Costume D’Homme. In 2018 the brand evolved yet again expanding into a line of perfume. His innovation has led to ground breaking collaborations and pop culture moments, working alongside household names of fashion, reinventing icons Like Dr Martins whilst dressing icons of entertainment from Tina Turner to Elton John. Most particularly his trailblazing Y-3 range with street-sports giant Adidas, spurned a new wave of cross-genre collaborations paving the way for the now billion-dollar athleisure industry.

Raised by his mother, who worked as a dressmaker. Yamamoto found himself identifying more with the women of his life. His compassion for the opposite gender would eventually present itself through the construction of his couture. His collections are built primarily around the comfort and confidence clothing can provide for women, uninterested in presenting them as objects of male desire.

Upon his graduation at Bunka Fashion College, he moved to Paris to carve a name for himself in the world of fashion. But it was a difficult time for the young designer. He rented a tiny flat in the city and spent nine months showcasing his freelance designs and sketches to fashion magazines, with little to no success.

“I felt I was totally useless,” he recalls of his early time in Paris. “I was sinking… to the bottom of the River Seine.” Yamamoto eventually conceded and returned to his home in Tokyo. His time in Paris, although unsuccessful, had convinced Yamamoto his calling was to become a designer.

Upon his return to Tokyo he worked for his mother, making dresses, and proved to be a frustrating disciple, baulking at the idea of simply replicating magazines styles for clients that clashed with their figures and constricted his creative freedom.

Outside the dressmaking shop, Yamamoto began to freelance on the side. His early designs set the template for the designs that would drive him to superstar status over the next decade: asymmetrically cut clothing that was loose and elegantly layered, designed to conceal rather than reveal; a mysterious and elegant new form of chic that clashed with the rigid and geometrically precise lines that dominated Parisian fashion at the time.

“Typically, Japanese women were wearing imported and very feminine things and I didn’t like it. I jumped on the idea of designing coats for women. It meant something for me — the idea of a coat guarding a home, hiding the woman’s body. Maybe I liked imagining what is inside.”

After working freelance for a number of years, Yamamoto decided it was time to open his first ready-to-wear boutique Y’s. However, just as it had been during his tenure in Paris, prospects as a store owner in those early years were bleak. His flowing armhole dresses of linen and woven cotton failed to make an impact on a Japanese market more interested in European and American fashion.

It was during this time that Yamamoto found an ally and partner in Rei Kawakubo, the eclectic designer and founder of Comme des Garcons. Despite radically different temperaments – Yamamoto a relaxed, affable personality quick to draw a smile, and Kawakubo the near inverse – they shared a commonality in couture. Both were attracted to the abnormal, unrestrained by conventional rules and tradition. Their aesthetic shared the same appreciation for the dirty, the imperfect, and the unencumbered; through very different prisms, both were searching for a new way to design for women.

It took a while to catch on, but eventually Yamamoto found success: his first public collection in Tokyo in 1977 became an instant success, and Y’s capitalised quickly as it expanded through the entire country:

“The wind was blowing. I had a map of Japan on the wall and I had a pin for each city where I had a connection with a shop.”

By 1980, he had nearly covered the map.

The time had come for Yamamoto to once again try his hand on the world stage. Ignoring his past failings, the designer opened a store in Paris in 1981; that same year he debuted at Paris Fashion Week in a collaborative show with Kawakubo that shook the foundations of traditional expectation.

Their dark, distressed, oversized garments bore no resemblance to anything that had ever been seen before and sharply polarised the audience:

“At the beginning, my memories are of more than 70 per cent of the audience booing and 30 per cent understanding or welcoming.”

Reaction from the Parisian press was bitter and more divided than perhaps anything the fashion world had ever experienced. Influential trade paper WWD ran photos of the collection scarred with black crosses over the top, describing it as fit for “intellectual bag ladies” and little else. Other publications lashed out at the designers, coining the collections as “Hiroshima” and “holocaust chic.”

Kawakubo, who actively sought to disrupt the status quo, relished her criticism. But for Yamamoto the response was deeply upsetting:

“I was simply looking for the idea for myself, for my own excitement. So, it was naturally out of trend, out of fashion. I was panicked by the reaction. I really felt I don’t mean that, I’m not coming here to Paris to say something against the fashion. I just wanted to open my own small shop. That’s it.”

Despite the protestations of critics, those same thirty per cent who applauded the collection were converts to this new sense of design. In fact, in a story that has become something of urban legend in fashion, demand was so high from buyers following his debut show that when they rushed the office at once to place orders the elevator broke from strain. It was better, it seemed, for people to react with love or hate than simple indifference. But for those who hated the collection, their crusade against this divergent form of fashion was far from over after that first showcase:

“From the next collection it became a war,” recalled Yamamoto. “I didn’t want a war but too much attack made me fight.”

Yamamoto and Kawakubo, who had endured her own vitriol following her debut in Paris, upped the ante for their 1982 collection. Kawakubo launched her seminal collection Destroy, an apocalyptic extension of her earlier work, further fuelling the antagonism between her and her detractors. Yamamoto continued forging his own path. Together they began to be seen as an invading wave of Japanese design.

“When one designer is thinking like that there is not so much reaction, but because there were two, it meant ‘the army from Asia.’”

It was a curious statement for a designer whose influences had little to do with his own culture. While Japanese traditions were lightly reflected in the loose kimono drape of his designs, Yamamoto, like most of Japan at the time, found more interest in European and American aesthetic – particularly the formation of punk fashion some five years prior to his Paris unveiling. Malcolm McLaren, godfather of punk, recalls both Yamamoto and Kawakubo as a pair of “excellent customers” when they arrived at his guerrilla store Sex during the late seventies.

Like many counter-culture followers through the decades, Yamamoto, and Kawakubo, were preoccupied with black. It was one of the most striking and divisive features of their early Paris collections and perhaps the most attractive quality of their garments. Although they were hardly the first to introduce black to Parisian fashion – Coco Chanel’s little black dress and the Yves Saint Laurent tuxedo spring to mind – there was an avant-garde quality to their use of the tone, a layered meaning that gave multiple contexts to a minimalist design choice:

“Black is modest and arrogant at the same time,” says Yamamoto. “Black is lazy and easy — but mysterious. It means that many things go together, yet it takes different aspects in many fabrics. You need black to have a silhouette. Black can swallow light, or make things look sharp. But above all black says this: ‘I don’t bother you — don’t bother me!”

The Yamamoto design aesthetic has evolved over the years, moving beyond the oversized silhouette of his early work and into the fitted couture representative of the times. Unlike many anti-fashion designers who deliberately work against the grain of the populist, Yamamoto is more concerned with following his own instinct and forging his own path, than he is with the expectations of others.

“I hate to look back; I’m always looking forward to what’s next. What can I do next?”

The only person he expects to outdo is himself. Each collection is designed to move him forward as a designer, as an artist.

Yamamoto’s career reached its zenith with the 1998 “wedding” collection. It confirmed the new, romantic path he had taken as he shifted register from masculine to feminine. The catalyst was his study of haute couture. He pored over the neo-Edwardian gowns of the American designer Charles James at the Brooklyn Museum of Art in the summer of 1999, when he was in New York to pick up an American Fashion Award. In the jigsaw of pattern pieces, he uncovered “another designer’s process.” Around this hype Yamamoto was also became the sole subject of a Wim Wenders documentary “Notebook on Cities and Clothes”.

Perhaps this searching for new inspiration is what led to him becoming one of the first designers to bridge couture with sport, collaborating with Adidas to produce the iconic “Y-3” sneaker back in 2001, long before athleisure was introduced to mainstream culture. Y-3 is the collaboration label between Adidas and Yamamoto, bringing the Japanese designers’ sartorial aesthetics to the sports brand, resulting in a fusion of high fashion and advanced performance wear.

Unveiled in Paris in 2002, the Y-3 brand celebrated its 10th collection with the Autumn Winter 07/08 men’s and women’s presentations in New York City. By 2016 Y-3 SPORT was launched a capsule collection which focused on functionality. The popular range of sneakers proved to be a big hit amongst celebrities and fashion influencers earning Yamamoto some serious street cred.

“When I started with Adidas for Y-3 it was very simple. At that moment 11 years ago, people started to call me ‘maestro of fashion’ and ‘king of cut’. I felt that I came too far from the street, so I wanted to come back to it. There I found sneakers jogging all over the world, so suddenly I wanted to work with sneakers as a way of getting back to the street. I made a phone call from my side to Adidas – “Why don’t you collaborate?” and they said yes at once. We started so-called sport couture.”

Despite his success as a designer, Yamamoto held little interest in the business side of couture. The lessons he had learned at Bunka College never truly stuck; Yamamoto preferred to handle the creative element of his company and let others handle his business.

The decision came back to haunt him. In 2009, Yamamoto filed for bankruptcy with debts of six billion yen but was rescued by a Japanese private-equity fund, Integral Group, which backed a rehabilitation effort which, under Japan’s Civil Rehabilitation Law, meant the business could continue to operate. At the time, Yamamoto told industry newspaper Women’s Wear Daily that problems arose in part because he “left too much to others”. Interesting, then, that he still thinks that the money side of the industry is “not my business”. The business eventually recovered and was in fact the subject of celebration in London 2011 cultural schedule, with Yamamoto first solo UK exhibition celebrating his life and work the key event at the acclaimed Victoria and Albert Museum.

When Selfridges asked Yamamoto to design a skateboard for their spring 2014 Board Games concept store, he answered with a deck that breathes new life into the iconography of the human skull, using profile x-rays of his own skull done years ago which were then traced meticulously by hand.

At this time he continued to explore his urban aesthetic joining forces with New Era, a US headwear brand hailing from Germany, whose iconic cap is the official gear of the National football league; Under his sub label Y’s, Yamamoto worked with them to reignite their icon: the 59FIFITY Cap with his graphic logo and insignia’s, and continue to release a series of headgear, including their most simplistic baseball cap to date: the 59TWENTY, a blank cap with Yojhi’s Signature. The collaboration evolved into a range including a line of apparel and accessories.

The Spring Summer ’18 goods celebrated Yamamoto’s rare turn to colour, featuring the skull and rose patterns from Yohji Yamamoto Homme’s Fall Winter ’14 collection. Followed by an expansive Fall/Winter offering, back into his key monochromatic palette.

In line with his historical film collaborations and ties to Japanese animation, Yamamoto’s work was referenced in the 2017 remake of the cult film Ghost in the Shell from Japanese Director Takeshi Kitano. The Yakuza characters in the film were very Yamamoto-like in monochrome loose tailored numbers. Yamamoto a fan of Kitano as well as a colleague having designed costumes for Kitano’s late nineties film BROTHER, answered back which a capsule line joint released with designer Fred Perry. Ground Y, Yamamoto’s more price friendly line, brought to life The Ghost in the Shell capsule collection which included Perry’s own classic polo and Yamamoto’s subtle design elements emblazoned with stylised illustrations from the manga series. 2018 saw Yohji Yamaoto also pair up with Ishimori Productions honouring the late Shotaro Ishinomori’s iconic Cyborg 009 manga character. The knitted apparel and t- shirt featured the Vintage manga characters and villain in a striking pop culture reference as manga nears its 52nd anniversary.

In 2019, Yamamoto returned to Paris with his critically acclaimed Spring Summer collection held in the historic Grand Palais. Though he is still the Patriarch of black in recent years he has introduced a broader palette continuing to work into his repertoire bold colour and loud prints for Summer. The darkened space was defined by the accompanying music, written in part by Yamamoto himself it represented his defiance of destructive forces, by replying with “anti-racism, anti-crazy global warming, anti-genderless fashion”, presenting a concept that clearly defined his vision for men and women as equal and separate. With signature oversized cuts and tailoring for the men and beautifully-unstructured drapery for the women that formed around the female body, across a line of dresses and outerwear and in later moments presented a more sensual silhouette with hardware and slithers of skin. His final act was an all-white colour palette that moved into bright colours, casting five black models to open and close the show. Whilst the clothes spoke for themselves, his abstract anti-vision may have been lost on critics, but it is more complicated than being just lost in translation.

According to Vogue’s Amy Verner, “Yamamoto has remained relevant precisely because there are so many unknowable aspects to his work, and people respect him immensely without overthinking why or how a collection materialises. Recent seasons have yielded themes that fluctuate between cheeky and profound, as though he is working through how to express himself in his advancing years.”

At a time when the gender neutral movement is afoot, Yamamoto’s presentation is at odds with times, but it less a battle against the cause than it is a means of reconnecting identity through clothing, with the brand as ever determined to forge their own path.

Before this, his Fall 2018 showing in Paris was one of his most poignant to date venerating the late fashion vanguard, friend and contemporary Azzedine Alaia. His passing, disrupted Yamamoto’s usual process, coming to him almost in a vision that challenged the sculptural fashion made famous by Azzedine against the master of Cubism, Pablo Picasso. This level of championing another designer, especially in show is not a common occurrence in the world of fashion, it was a moment that collided the unlikely masters, whom like two sides of a coin, were equally valued for their contribution. The collection placed notes of sculptured details from the oversized collars and lapels amidst Yamamoto’s own signature volume with deconstructed cubist moments that even went 3-dimensional. The patch worked leather corsets and classic tailored coats resembled some affinity with the “King of Cling”, not unnoticed by Alaia’s inner circle, whom were in attendance for the touching tribute.

There was not a dry eye in the house. The catharsis even took a toll on Yamamoto himself, emotionally and physically bringing him to question his own footing in a new era of designers and the legacy of his life’s work. The last of the longstanding designers to remain staunchly independent and maintain relevant collaborations across several decades.

In his life, Yamamoto has managed to capture his craft, memories and musings in a holistic autobiography unlike anything else. My Dear Bomb encapsulates his style and his efforts to understand his critics as part of his personal evaluation. It is not chronological rather a fusion of poetry, anecdotes and trade notes. His previous publications “Talking to Myself” and “Y’s-Yohji Yamamoto” are an open door into the genius of Yamamoto. At 75, Yamamoto has always disregarded the idea of retirement and practices fierce dedication to the craft and his team. Certainly, this renegade of fashion will fight off his final chapter.

Check back every Tuesday for the latest teaser for FIB and Style Planet TV’s newest docuseries, Renegades.

Written by: Charlie O’Brien

Edited by: Jess Bregenhoj