(On that note, I heartily recommend 1999’s High Concept, Charles Fleming’s account of Hollywood personalities and the lives of excess they lived with a particular focus on Simpson, who’d been dead three years by then after his hard-living ways.)

Power in Hollywood has always swung between creative classes depending on the business climate surrounding the industry at the time. I recently had the pleasure of interviewing Nick De Semlyen of Empire magazine, who was plugging his ace book Wild and Crazy Guys (all about the comedy stars who made the 80s what they were), and he said something very interesting.

The 70s was the era when directors had all the influence. In the 80s it shifted to actors, and it was during that time we started to see agents appearing on ‘most powerful’ lists and stories about stratospheric actors salaries. I can still remember when Sylvester Stallone commanded such an unheard-of sum for Rambo: First Blood Part II ($12m) it made the nightly news.

And while producers have always been powerful, they’ve never been as powerful as they are now, or as visible. We live in an era where a hit film just isn’t enough. What you need to succeed nowadays is a hit franchise.

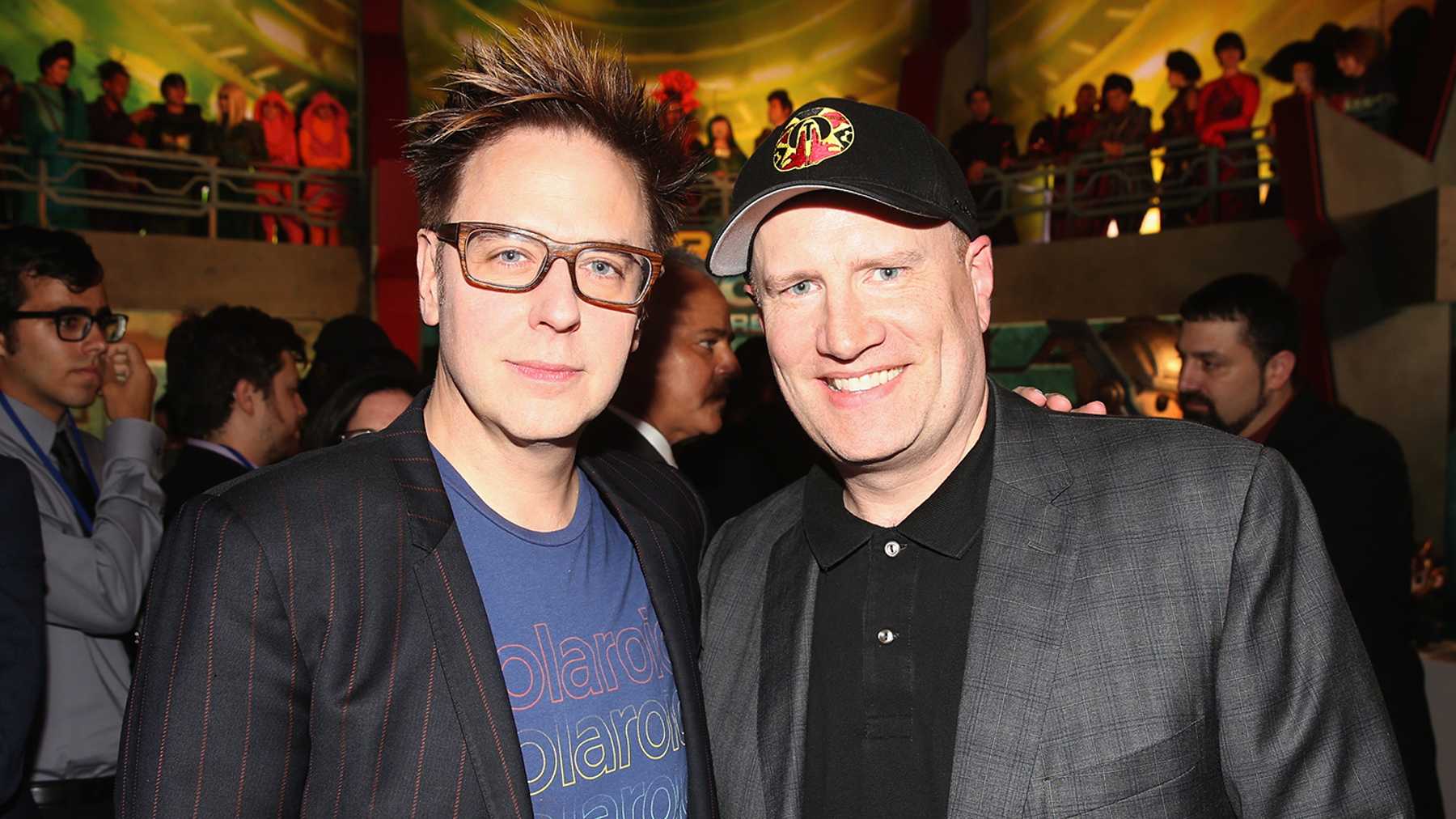

And while Peyton Reed, The Russo Brothers, Shane Black, Jon Favreau, Taika Waititi, Joe Johnston, Alan Taylor, James Gunn, Joss Whedon, Scott Derrickson, Ryan Fleck, Anna Boden and Jon Watts have presided over films that have made hundreds of millions and in some cases over a billion dollars and are unquestionably powerful directors as a result, there’s just one name who sits in the highest branch of the Marvel tree above all of them, Kevin Fiege.

But what’s even more interesting about Fiege is the kind of producer he is. He’s not just sending out emails to directors offering them jobs. As this Variety profile reveals, Fiege is extremely hands on. Nestled in an infographic about how busy he is, the most telling details are the participation in meetings about visual effects, post-production colouring and costuming.

If pressed, Fiege would undoubtedly have given the interviewer the scripted line about having full faith in his directors and supporting their vision, but normally the buck of creative details like those mentioned above would stop no higher than the director.

If you ask me, it confirms something we’ve always felt but haven’t really had evidence for, especially after the very high profile parting of ways between the company and Edgar Wright over Ant-Man. As the creative steward of the entire MCU, Fiege is the overall director with ultimate final cut while Reed, Gunn and the rest are mere shooters-for-hire.

Photo Credit: Empire Online.

You can imagine the same thing elsewhere in the Disney corporate behemoth with Kathleen Kennedy. In consultation with a core story group, she seems to exert iron control over strict adherence to the quintessential brand of the franchise. And woe betide any director who either doesn’t toe the company line or brings any stink of commercial failure with them.

As soon as we all stumbled out of Rogue One: A Star Wars Story we supposed Gareth Edwards had managed a cinematic hat trick with his first three movies as a director but as we all discovered later, it had been a nightmarish production with Tony Gilroy bought in to patch things up. Of course all concerned gave the press the usual bland kumbaya about how seamlessly they all worked together and how necessary the extra work was, but rumours that Edwards had the movie basically taken off him persist.

After that, LucasFilm’s very public split with original Solo: A Star Wars Story directors Phil Lord and Chris Miller smelled mightily like the fallout between Wright and Marvel a couple of years before, no matter how much everyone trotted out the amicable split love-fest story.

And of course, Colin Trevorrow might have been burned the worst. A newly minted member of the billion dollar club thanks to Jurassic World after helming only a single small scale sci-fi romp (Safety Not Guaranteed), Trevorrow seemed tailor made for the Star Wars director’s roster. A single embarrassing flop later (The Book of Henry), and he was bantha fodder.

On the surface it might not seem different from the old days. In the metaphor of a movie as a company, the producer can be thought of as the chairperson, and in that capacity he/she has always had hiring and firing power over the director, who’s more the CEO tasked with running the company on a everyday basis and bringing the product or service to market (ie screens).

But today’s megaproducers preside over much bigger and more expensive ventures than just standalone movies, and in an age where even a single film costs more than studios in the 80s used to spend in six months (even adjusted for inflation), the franchises they’re comprised of represent multi-billion dollar acquisitions to their corporate owners.

You better believe those at the helm are going to exert iron-fisted control over the pesky, self-indulgent, black turtleneck and beret wearing directors getting all angsty over their art…

On screens recently, I along with the rest of the world mainlined peak MCU straight into my veins with Avengers: Endgame. I caught up with glossy awards-bait Roma and learnt a few lessons originally taught by Hitchcock. But the most interesting experience was with Netflix’s Choose Your Own Adventure tale Black Mirror: Bandersnatch. Though it might seem unnecessarily hyperbolic, I thought we might have seen a glimpse of the future.

Subscribe to FIB’s newsletter for your weekly dose of music, fashion and pop culture news!