David Lynch has defined American cinema for over forty years despite entering semi-retirement some time ago. But Lynch has returned with his sequel to the acclaimed Twin Peaks and his new short What Did Jack Do? on Netflix.

It’s been fourteen years since the release of Inland Empire, the most recent film by David Lynch. The director, a staple of American cinema since his debut Eraserhead and the Mel Brooks-produced The Elephant Man, has been strangely absent from the big screen. But this absence isn’t an indication that Lynch is uninspired. In fact, Lynch has been steadily churning out short films, albums, music videos, and even releasing a video of himself cooking quinoa.

As of January 20th, to celebrate his 74th birthday, Lynch has released a 17-minute short on Netflix titled What Did Jack Do? Lynch plays an unnamed detective interrogating a monkey named Jack Cruz. The titular Jack, in true Lynchian style, is evasive, sincere, and vulgar. Eventually, Lynch extracts a confession from the homicidal monkey, who admits to a broken heart after a romance with a chicken named Toototabon. Jack even sings a song for his unrequited love, now available online.

Originally screened in 2017 at Parisian museum the Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporain, What Did Jack Do? will have to hold Lynch fans over until his next film or television project. “I would not make a feature film in today’s world because the kind of films I make couldn’t be on the big screen for very long,” Lynch told Rory Carroll of The Guardian. Lynch is famously reclusive, living in a compound of three adjacent houses and a studio in the Hollywood Hills, and has adopted a lifestyle of semi-retirement from film.

Despite this, What Did Jack Do? and Twin Peaks: The Return is proof that the director hasn’t lost his strange and surreal touch. But after so long, have audiences become accustomed to Lynch’s brand of cinema and saturated with films inspired by the all-American iconoclast?

A Candy-Coloured Clown They Call David Lynch

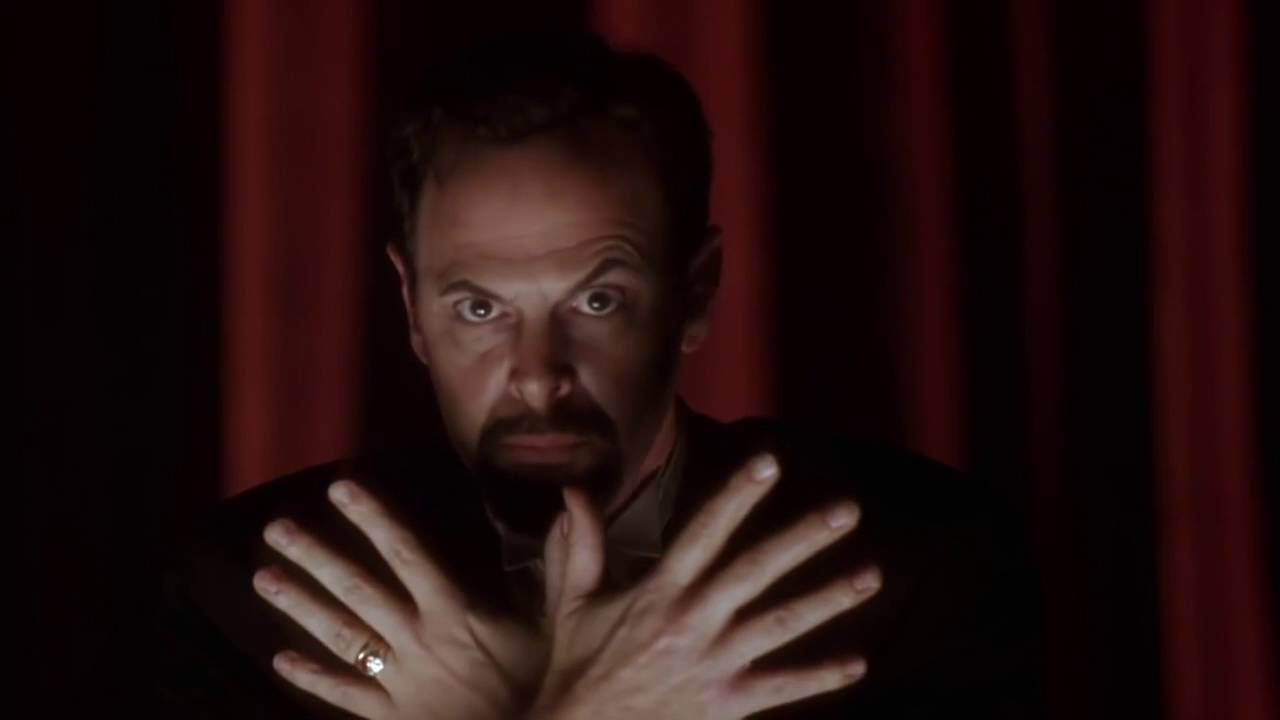

What exactly divides Lynch from his contemporaries? Is it the strangeness of his films? The undercurrent of violence? Nightmarish figures like The Mystery Man in Lost Highway, Killer Bob in Twin Peaks, Frank Booth in Blue Velvet?

Well, strangeness in cinema isn’t unique to Lynch. Rather, it’s only unique to the corner of mainstream American cinema that Lynch carved out. Lynch has cited time and time again his love of Italian filmmaker Federico Fellini, a fellow auteur of the bizarre with films like 8½ and the Toby Dammit segment in Spirits of the Dead. Lynch feels as strange as he does because of how he marries the style of European cinema with the economic motivations of Hollywood.

As for violence, Hollywood has no lack of that in its films. Notably, violence in Lynch’s work is as much about the nefarious presence of violence more than the act itself. The ear in the field that Jeffrey Beaumont, played by long-time collaborator Kyle MacLachlan, finds at the beginning of Blue Velvet is the perfect example. Lynch shows neither shows the action of the slicing or any blood from the ear, unlike another ear-cutting scene in Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs. Instead, it’s the shadow of violence that pulls MacLachlan’s character into the story, as it would again four years later in Twin Peaks as Agent Cooper.

Lynch’s characters are perhaps that aspect of his films that are most authentically his, stemming from a personal style more than a cinematic tradition. But that doesn’t mean that cinematic tradition doesn’t inform his characters. Lynch creates his characters as reflections of what he associates film with most: dreams.

“The Wizard of Oz is a cosmic film and meaningful on many, many different levels”

One of Lynch’s favourite films, The Wizard of Oz, draws parallels between dreaming and watching a film. Dorothy experiences a world where she is both in control and completely at the whim of the world. The various people of Oz need Dorothy, the omnipotent spectator, to overthrow the Wicked Witch. But Dorothy herself is a stranger in a strange land, relying on the help of her friends to guide her to defeat the Wicked Witch and get home. “The Wizard of Oz is a cosmic film and meaningful on many, many different levels,” said Lynch in an interview with The Observer.

Lynch’s work often pays homage to The Wizard of Oz, poaching characterization, cinematography, musical choices, and the overall themes of the film. Just like Dorothy, Lynch’s protagonists like Jeffrey Beaumont, Fred Madison (Bill Pullman in Lost Highway), and Betty / Diane Selwyn (Naomi Watts in Mulholland Drive) find themselves in alienating situations and locations.

The true heart of Lynch’s films is the brand that is David Lynch. Lynch, despite what his films might suggest, is himself a happy and friendly individual. His idyllic upbringing in 1950s America echoes the iconography of that period: apple-pies cooling on the windowsill, long summers spent outside until the streetlights came on, teenagers sharing a malt at the local diner. Lynch even spent his boyhood as a scout, eventually rising to the highest rank of Eagle Scout.

At first glance, this childhood seems at odds with his work. But it’s this very idealism that the prosperous fifties exuded that defines his work. Lynch’s brand of strange comes from taking his intrinsic American idealism and trying to push it into the round hole. The sincerity of his characters stands out against the narratives they find themselves in. Everyone’s an idealist, you just not might like their ideals.

Mr. Lynch, You’re No Elephant Man, You’re Romeo

Why does the interrogation between Lynch and Jack Cruz reaffirm the formers importance? What Did Jack Do? holds nothing entirely unusual in the surreal world of Lynch. That’s because aesthetic choices like a balladeer capuchin or the German expressionistic set aren’t the core components to Lynch’s films. It’s the dialogue, or more appropriately the act of communication, that conveys the most Lynchian aspects of his films.

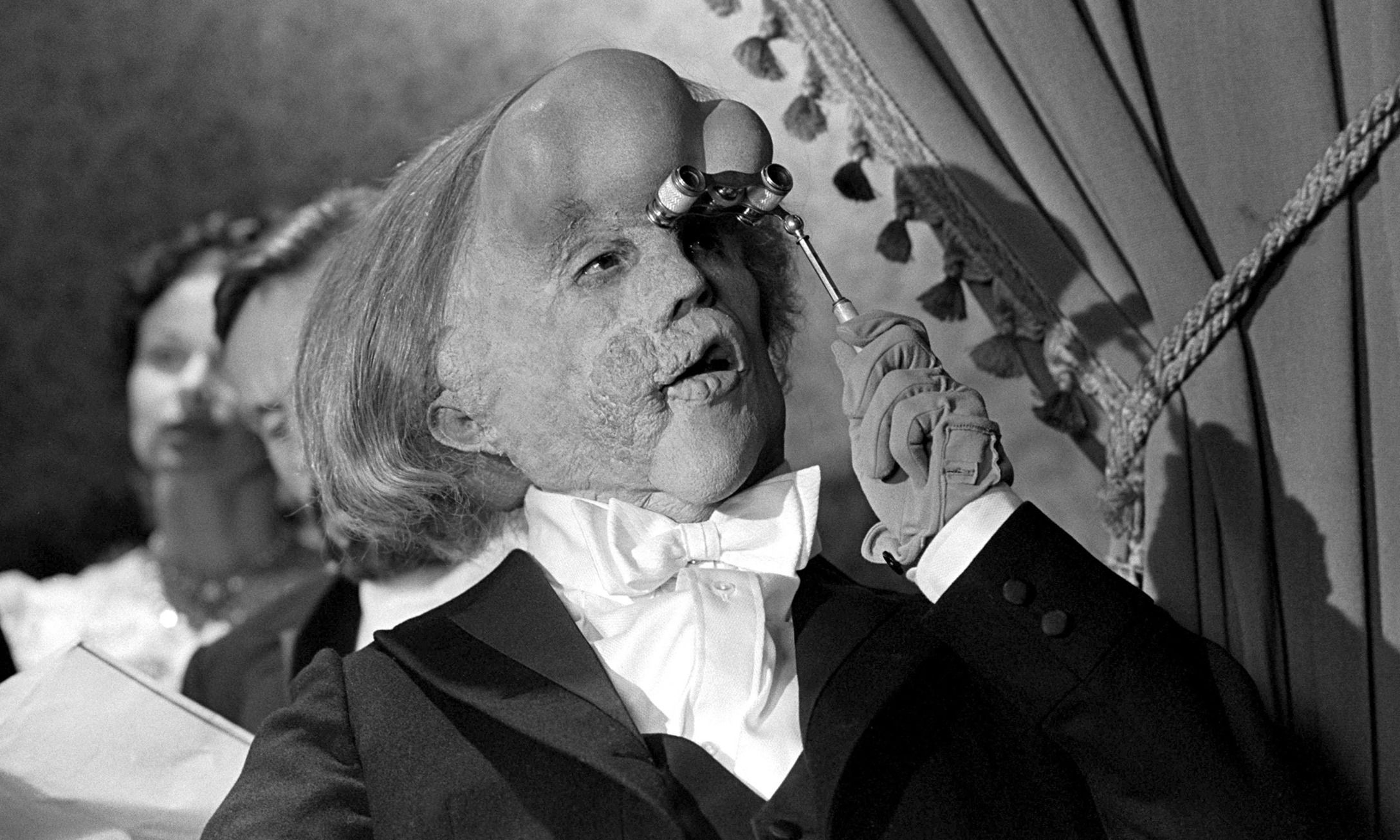

This is the diner scene in Mulholland Drive, the introduction of Frank Booth in Blue Velvet, John Merrick and Madge Kendel performing Shakespeare in The Elephant Man. The Lynchian qualities however extend beyond the dialogue and into the technical aspects of filmmaking.

Mulholland Drive exemplifies this, between the acting, camera movements, and sound design. As the man recounts his dream to his friend, his face bends and twists into exaggerated expressions. The constant camera movements only adds to this anxiety in the acting. The scene’s climax, as the two men investigate behind the diner, builds the sound design to an almost intolerable interference of background sound and orchestra.

“It’s a delicate thing sometimes. All the time it’s a delicate thing. Too loud or the wrong sound can throw you out. So it’s a grand experiment to get everything to feel correct.”

Lynch’s attention to sound is itself a unique relationship. Of the twelve major works in his filmography (his ten films and both Twin Peaks and Twin Peaks: The Return) David Lynch was credited as part of the sound department for eight. It’s rare that a director pays such careful attention to produce a unique sound design. In an interview with The Hollywood Reporter, Lynch was asked about his role in the sound design. “It’s a delicate thing sometimes,” Lynch said. “All the time it’s a delicate thing. Too loud or the wrong sound can throw you out. So it’s a grand experiment to get everything to feel correct.”

These filmmaking elements all come together to create Lynch’s iconic scene structures. Camerawork and sound are edited to perfectly enhance the performances and elicit that unmistakable style. To create those truly unforgettable scenes, Lynch’s films possess a jazz-like quality where rhythm, tension, and intimacy are intertwined in the technical.

His characters pause while they talk, as if they can hear the orchestra building or as if just now the ridiculousness of their speech has just hit them. They wear their ideals, never hiding who they are under their words. But as Lynch does this, the opaque and surreal dialogue reveals the complexity that comes from holding these ideals in this dreamlike world.

“The language of film, cinema, is the language it was put into, and the English language – it’s not going to translate.”

“We’re like the dreamer who dreams and then lives inside the dream,” muses Gordon Cole (Lynch’s character in Twin Peaks: The Return), “But who is the dreamer?” It’s exactly these questions that makes Lynch’s films so unique; not for the style but because, unlike other director’s, Lynch doesn’t want audiences to try and define his films themselves.

As Lynch said to Carroll, “A film or a painting – each thing is its own sort of language and it’s not right to try to say the same thing in words. The words are not there. The language of film, cinema, is the language it was put into, and the English language – it’s not going to translate. It’s going to lose.”

It goes to show that while interpretation is altogether an important part of responding to artistry, we should not look to provide set definitions. We should instead look to interpretation as the means, not the end, to understanding. In some sense, that’s what What Did Jack Do? was addressing. We can question the intention behind an action, whether that action is making a work of art or an act of murder. But in the end, art has no one voice and that monkey was just dubbed by David Lynch.

Subscribe to FIB’s newsletter for your weekly dose of music, fashion and pop culture news!