We can take the rag away from our faces; Dylan’s latest composition is a true homecoming.

“It was a dark day in Dallas, November ’63 / A day that will live on in infamy.” In other words, “’Twas in another lifetime / One of toil and blood.” It’s fitting that perhaps the greatest allusory artist of the modern era has come full circle, with the opening lines of his recent single ‘Murder Most Foul’, emulating the beginning of the penultimate track ‘Shelter from the Storm’, on his classic album Blood on the Tracks.

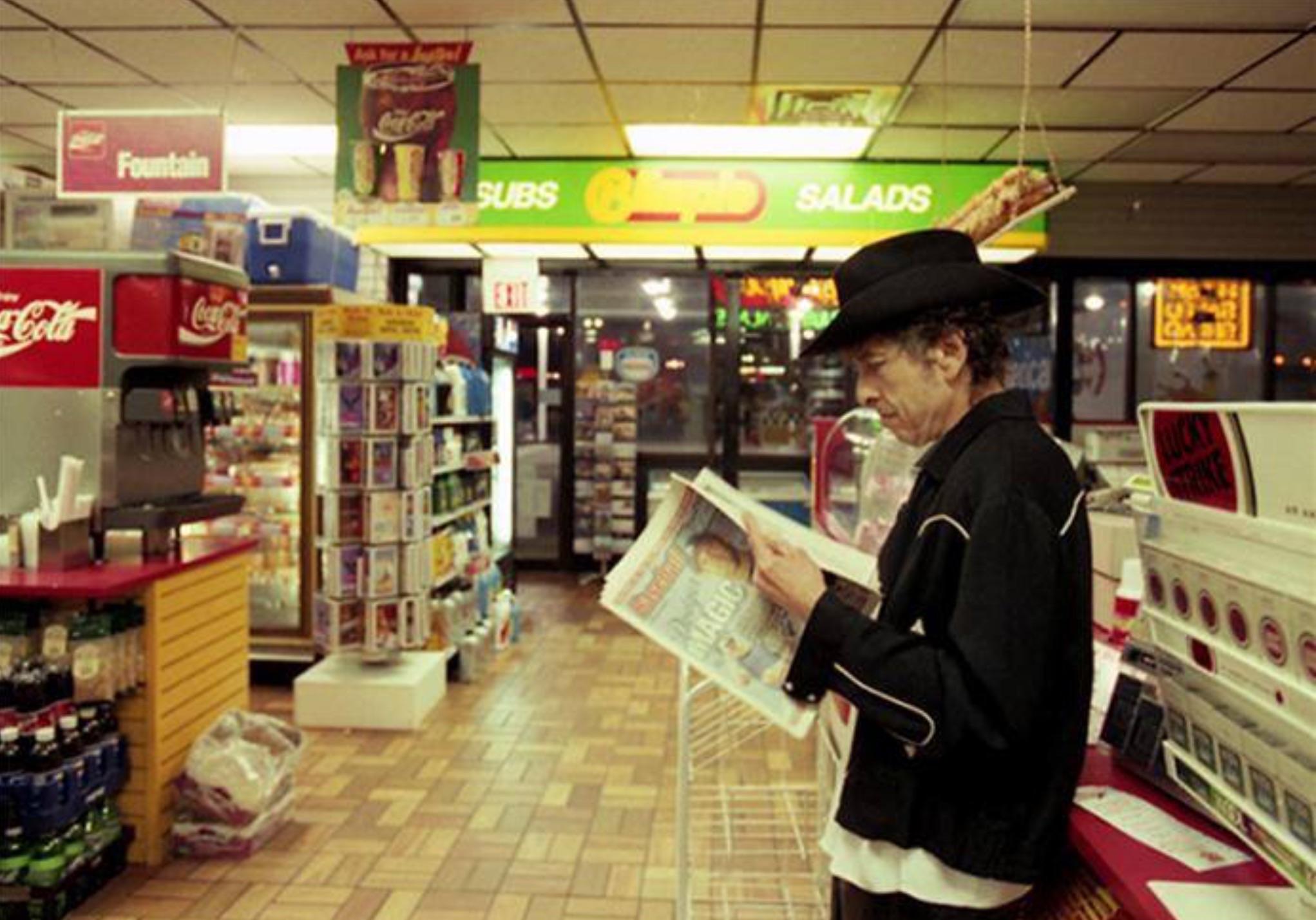

On the 27th of March, Bob Dylan released his first original in eight years titled ‘Murder Most Foul’. Not since the album Tempest in 2012 has Dylan sung an original new composition. His last three albums, Shadows in the Night, Fallen Angels, and Triplicate have all been Tin Pan Alley songs, the sort of music Dylan grew up hearing on the radio and has a long-lasting affinity for.

But with this 17-minute song, Dylan has returned to the spotlight with an oevre that is as significant a release since Time Out of Mind in 1997. Tackling John F. Kennedy, American social decay, and the endurance of art, Dylan espouses a sermon in a way that only he could pull off.

Someone’s got it in for me, they’re planting stories in the press.

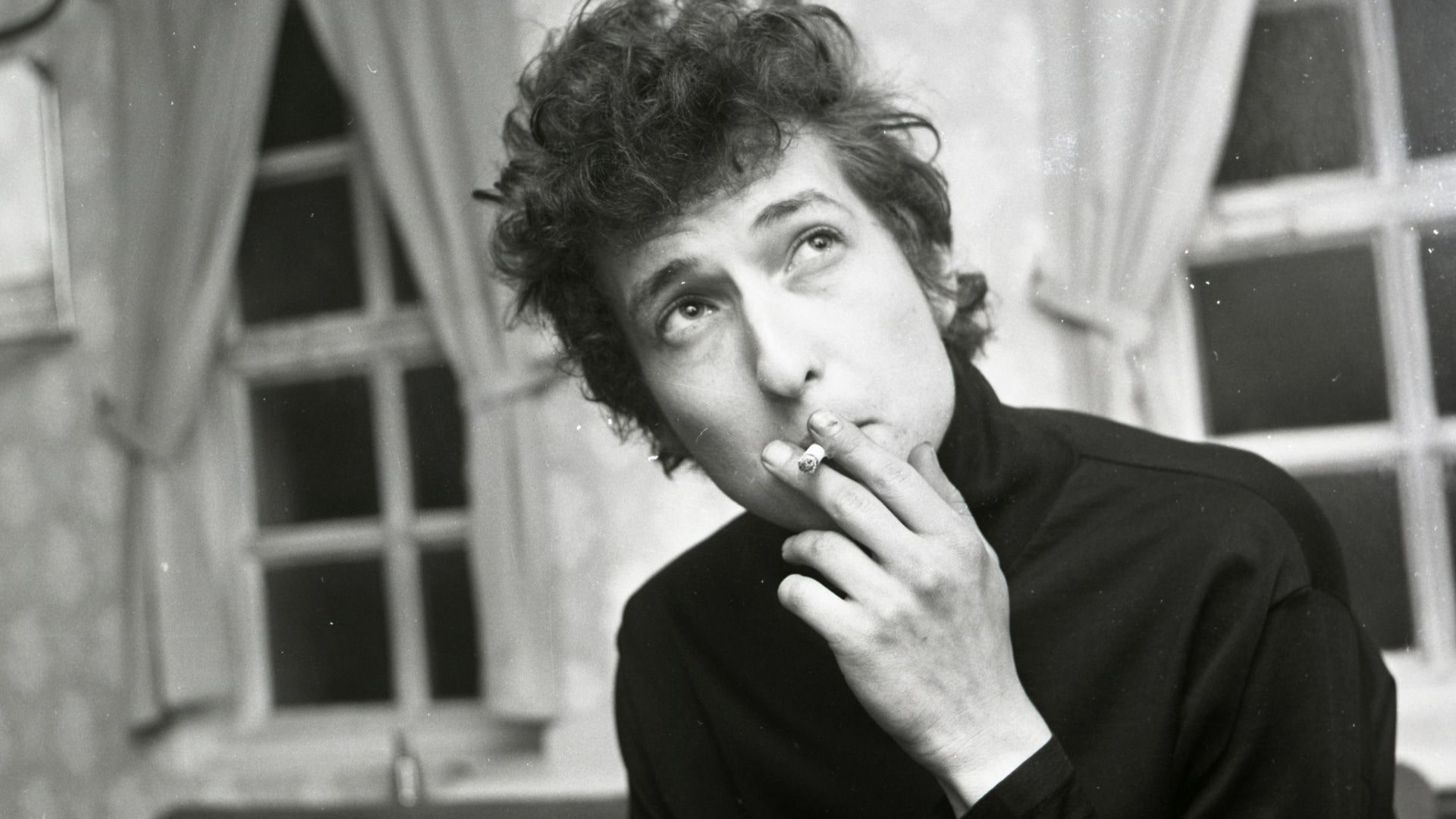

Bob Dylan is, without a doubt, the most influential singer-songwriter in American history. Back in the 1960s, Dylan emerged onto the Greenwich Village folk scene with a comprehensive understanding of America’s mystic past, its volatile present, and its limitless future. Learning from musicians such as Woody Guthrie, Hank Williams, and Robert Johnson, a veritable Holy Trinity of American musical breadth, Dylan’s sophomore album The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan added to annals he admired. Songs like ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’, ‘Masters of War’, and ‘A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall’, cemented Dylan as a staple of the folk scene and were covered by peers such as Peter, Paul, and Mary, Joan Baez, and Marianne Faithful.

His follow-up The Times They Are-A Changin’ was his most socially conscious work and spawned a bevy of beloved songs. But Dylan’s moment in the spotlight ended up classifying him into the narrow niche of Protest Singer. He was crowned “the Voice of a Generation”, a title that his contemporaries did nothing to dissuade. Don McLean’s ‘American Pie’ described Dylan dressed as James Dean with “a voice that came from you and me”. David Bowie sung of a voice “with sand and glue” in his tribute on Hunky Dory, ‘Song for Bob Dylan’.

Dylan’s rejection of the title came to its breaking point when, on December 13th, 1963, not even a month after Kennedy’s assassination, Dylan was awarded the Tom Paine Award by the Emergency Civil Liberties Committee for his civil rights work. Dylan, nervous and drunk, gave a speech upon his acceptance of the award. “I want to accept it in my name,” Dylan stated, “but I’m not really accepting it in my name and I’m not accepting it in any kind of group’s name, any Negro group or any other kind of group”.

He went on, denouncing the sort of people that awarded him that night, “my friends don’t wear suits. My friends don’t have to wear suits. My friends don’t have to wear any kind of thing to prove that they’re respectable Negroes”. He then became inflammatory in his remarks, almost intentionally; after criticising the travel ban on Cuba, he turned his focus on the fallen president.

“I have to be to be honest, I just got to be, as I got to admit that the man who shot President Kennedy, Lee Oswald, I don’t know exactly where — what he thought he was doing, but I got to admit honestly that I too — I saw some of myself in him. I don’t think it would have gone — I don’t think it could go that far. But I got to stand up and say I saw things that he felt, in me — not to go that far and shoot. [Boos and hisses] You can boo but booing’s got nothing to do with it.”

It was a highly contentious incident and the beginning of the end for the Voice of a Generation moniker that had followed him those previous months. Eventually, the Oswald speech became only a vague memory in a cycle of rebellion that would define Dylan, as he went electric and crashed spectacularly out in Woodstock. The nearest chronicle of that night, beyond the memory of ardent Dylan fans, could be found in the unreleased ‘Dignity’.

Drinkin’ man listens to the voice he hears

In a crowded room full of covered up mirrors

Lookin’ into the lost forgotten years

For dignity.

Conjuring up all these long dead souls from their crumbling’ tombs

Since then Dylan has pulled his focus back to that dark day in Dallas, if it ever really left. Maybe Kennedy was that dying gunfighter played by Gregory Peck or the nameless wanderer on a Texan odyssey, both from the 1986 song ‘Brownsville Girl’. Or maybe Dylan was once again sharing a skin with Oswald in the Homeric Tempest when he sung in ‘Pay in Blood’: “I’ll give you justice, I’ll fathom your purse”. Did Dylan tear a page out of some diary of agendas written in by the deceased president when he crafted ‘Honest with Me’? “I’m here to create the new imperial empire / I’m going to do whatever circumstances require”.

Dylan is nothing if not a master of allusion. This language technique, a staple of the great modernists like James Joyce and T.S. Eliot, was a way of communing with the dead. It’s how Joyce embodied Stephen Dedalus so effortlessly through parallels to his Greek counterpart, the famed inventor. It’s all over Eliot’s masterpiece of poetry The Wasteland. And Dylan has never been shy to invoke the words of his ancestors, to the point where he got into some legal trouble after the release of his 2006 album Modern Times, where his allusion and devotion to the folk process was decried as copyright infringement.

But – apart from his controversial spot in the limelight with the winning of the 2017 Nobel Peace Prize for Literature – Dylan has been mostly silent in the past eight years since Tempest was released. His masterful integration of the language of others was put on hold when he picked up the Great American Songbook and crooned his voice out of its elder statesman growl. Now, armed with his Sinatra era vocals, Dylan has crowned this year as his homecoming, a troubadour’s return. He’s picked up where he left off and made up for lost time while he’s done it.

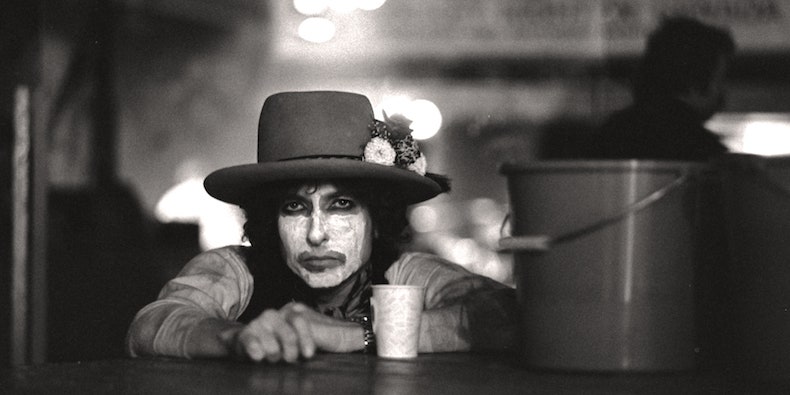

Allusion is the bread-and-butter for this single. ‘Murder Most Foul’ is itself a reference to Act 1, Scene 5 of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, when Prince Hamlet sees the ghost of his father, the King of Denmark. “Murder most foul,” cries the King to his son, “as in the best it is; / But this most foul, strange, and unnatural.” The Ghost of the King is referring to his murder at the hands of his brother Claudius, itself a powerful Biblical allusion to Cain and Abel. From the get-go, Dylan sets up ‘Murder Most Foul’ as a time machine, a Neil Young-style bending of time and space.

Wear these old laurel leaves that he’s shaken from his head

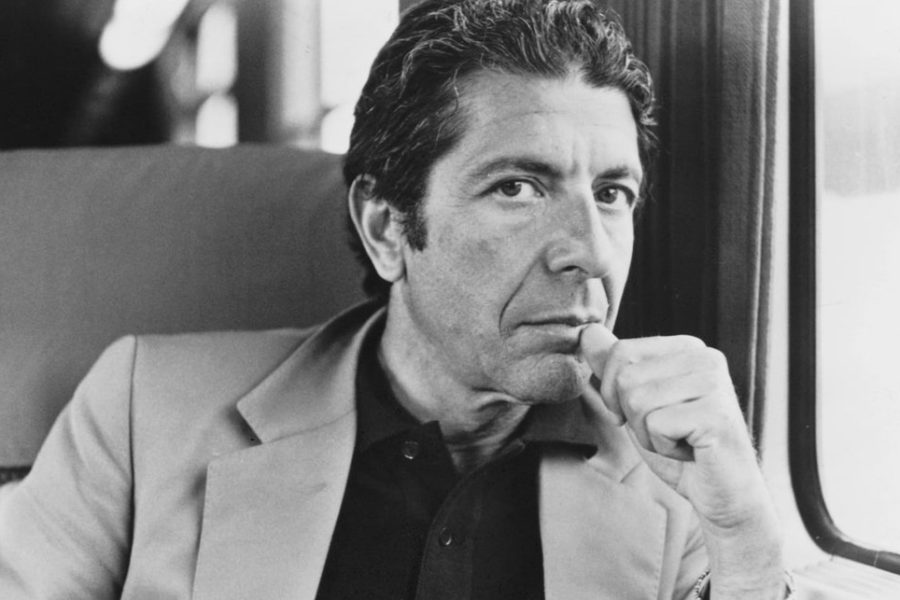

Before delving too deeply into the allusions and meanings of the song, there’s one noticeable and strange absence. Beyond Dylan’s musings on fratricide and spirituality, as well as the entire song’s structure and vocal performance, ‘Murder Most Foul’ is a strong reminder of Leonard Cohen, a consistent champion of Dylan and one of his few challengers as the most adept modern lyricist. Cohen’s work was spiritual, violent, erotic, desperate, and depressed. As Dylan sings of Kennedy being “led to the slaughter like a sacrificial lamb”, Cohen was amongst them in his song ‘Stories of the Street’ where he sang:

And if by chance I wake at night

And I ask you who I am,

O take me to the slaughterhouse,

I will wait there with the lamb.

Sacrifice is a staple of Cohen’s work: in ‘Story of Isaac’ he recounts the oldest Jewish sacrifice (as did Dylan in ‘Highway 61 Revisited’), ‘Chelsea Hotel #2’ paints Janis Joplin’s death as just another sacrifice of the poetic (“I don’t keep track of each fallen robin / I remember you well in the Chelsea Hotel / That’s all, I don’t even think of you that often). And ‘Tower of Song’ depicts the pressures of writing through sacrificial imagery (“And twenty-seven angels from the Great Beyond / They tied me to this table right here in the Tower of Song”).

Dylan’s ‘Murder Most Foul’ also strongly mirrors the deeply complex music of The Future, especially songs like ‘Democracy’ and ‘Waiting for the Miracle’, with their atmospheric qualities and dark dwellings. Cohen’s ‘Democracy’, for example, structures its first verse as a thesis on itself, describing “the wars against disorder,” “the sirens night and day,” “the fires of the homeless,” “the ashes of the gay” and that, eventually, “Democracy is coming to the USA.”

‘Murder Most Foul’ isn’t as enigmatic as ‘Democracy’, its events fairly historical if not dramatised. Rather ‘Murder Most Foul’ begins its first verse with a recount of Kennedy’s assassination, making it more linear than Cohen’s anthem for the United States. But those inflections, authoritative without pressure, have a strong Cohen quality. Dylan has performed in a similar way before on ‘Long and Wasted Years’ from Tempest and in his recorded Nobel Prize speech. It’s an innate rhythm in delivery that Germany calls sprechgesang or spoken singing.

Yet Cohen isn’t mentioned in the song’s great list of artists (except, perhaps, where Dylan may have mentioned his song ‘Darkness’ from Old Ideas in the final lines). Instead, Dylan integrates the shadow of Cohen’s style into his 17-minute epic as a memorial to the late poet-musician. Yet there are plenty of other characters who appear in ‘Murder Most Foul’ and a greater statement to made.

My telephone rang, it would not stop / It’s President Kennedy calling me up

“Greetings to my fans and followers, with gratitude for all your support and loyalty across the years. This is an unreleased song we recorded a while back that you might find interesting. Stay safe, stay observant and may God be with you” – ” message from Dylan’s Twitter account

Naturally, one of the biggest questions amongst Dylan followers is exactly when was the “while back” when Dylan recorded this single? Was it during one of his periodic breaks between the Never-Ending Tour? Was it back around 2012, when Tempest was released? It certainly has a similar length and writing style to the titular song about another true tragedy, the sinking of the Titanic. Or from the abandoned religious album that Dylan was working on before he switched to Tempest instead? What most agree on is that Dylan’s vocal quality is a distinctive croon, reminiscent of Triplicate, Dylan’s final (for now) Sinatra-style album.

If it was indeed recently recorded, does that mean a new album is on the way? Rumours circulated some months ago about a new album coming from Dylan titled Days of Yore. Could ‘Murder Most Foul’ be a herald for an imminent release? Triplicate, his most recent album, was released in late March 2017, a similar date to ‘Murder Most Foul’? Dylan will likely not say anything about a new album; he’ll either confirm its release or ignore its possibility altogether.

But until then, Dylan has gifted his longest song to date, overtaking the previous titleholder ‘Highlands’ by about 30 seconds. And the way pop culture and allusion intersect in the lyrics, guided by Dylan’s vocals and backed by a sparse and staggered instrumental composition, makes the song hypnotic on multiple listens.

Dylan wants his listeners to understand the value of art as a constant, an uncompromising reflection and chronicling of our values. The idea that America isn’t defined solely by its economics and politics, that American art and a mythologised legacy is what makes the country so unique. Kennedy spoke of a new frontier, ironically set in stone by his death, and Dylan answers this by invoking both frontiers.His lyrics invite the characters of his contemporaries’ works into ‘Murder Most Foul’: the Beatles’ Miss Lizzy from ‘Dizzy Miss Lizzy’, The Who’s Acid Queen from the song of the same name, and Tommy from their landmark album Tommy.

It’s not just musical references that appear in the song; Dylan makes mention of multiple films. Wes Craven’s Nightmare on Elm Street (Elm Street was the street name that Kennedy was shot on), the Abraham Zapruder home movies of the assassination, Gone with the Wind, and Frank Capra’s It Happened One Night and more all come into the song.

Dylan concludes his song with a request for famed DJ Wolfman Jack. His list of songs ranges from Etta James and Cab Calloway to Don Henley and Queen, reminiscent of his 2006-2009 radio show Theme Time Radio Hour, in which Dylan would pick songs according to a set theme such as baseball, coffee, and questions.

Dylan invites more than just musicians to listen with him to Wolfman Jack’s radio show, calling on such figures as Marilyn Monroe, Houdini, the Birdman of Alcatraz, and Lady MacBeth. He asks for some classic films too, slapstick and stuntmen like Harold Lloyd and Buster Keaton, and outlaws like Bugsy Siegel and Pretty Boy Floyd. He wants jazz, blues, folk, country, classical, national anthems, jingles.

At it’s heart, ‘Murder Most Foul’ is a dirge, a funeral song for American ideals. Wolfman Jack is here to transport us back in time and space through music. The deceased DJ takes us back to the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921, to the murder of Laura Foster and the hanging of Tom Dula, to The Beach Boys’ guitarist Carl Wilson’s drowning. Dylan’s final request of Wolfman Jack is to “play ‘The Blood-Stained Banner’, play ‘Murder Most Foul’”.

To play ‘Murder Most Foul’ within ‘Murder Most Foul’ is to invoke a metaphysical displacement; to witness the assassination again, not out of a desire to change the past but to observe and understand it better. Dylan knows what went wrong with the American Dream, with ‘Manifest Destiny’, and he remembers that day: “It was a dark day in Dallas, November ’63.” To quote Cohen’s ‘Anthem’, we can see the advantage of any dark day, “There is a crack, a crack, in everything / That’s how the light gets in’.

Subscribe to FIB’s Weekly Alchemy Report for your weekly dose of music, fashion and pop culture news!