The legendary conceptual artist’s six minute film teaches us about simplicity and style.

Marcel Duchamp was a simple man. His art was based on ideas, and he took great trouble to present these ideas in their purest form. His revolutionary work, Fountain, a urinal signed with the initials R.Mutt, outraged the art world, and essentially created conceptual art whilst also destroying it. Once the concept was born, the concept was finished. Since anything could be art, nothing could be. Duchamp is remembered mostly for this work, but spent a lifetime creating and thinking, always working in an elegant, comical way.

Duchamp’s ‘Readymades’ were objects left untouched and untampered with presented as completed works of art. These included a bicycle wheel, a bottle rack and a shovel which Duchamp titled ‘In Advance Of A Broken Arm’. This type of creation is both limitless and limited. Anything could truly be a Readymade, but Duchamp chose his items carefully based on their ‘visual indifference’, and spent months analysing his own work, primarily in his own mind. He was a thinker as much as he was an artist, living a simple life in a small apartment, occasionally writing, smoking cigars, watching the world go by. Duchamp’s art making culminated in a piece titled The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even, which he worked on from 1915 to 1923. This large panel of glass, wire, foil and dust is unclassifiable and baffling, presenting Duchamp’s ideas about art on a larger, more grandiose scale.

Moving on from Readymades, Duchamp became interested in what he called ‘Rotoreliefs’. These worked in a similar way to spinning top toys. Duchamp would paint on cardboard and spin the cardboard on a turntable, creating a hypnotic, three-dimensional effect. Whilst a commercial failure, Duchamp’s Rotoreliefs presented a challenge to the world of art and film, with Duchamp truly challenging the extents and the purpose of retinal art.

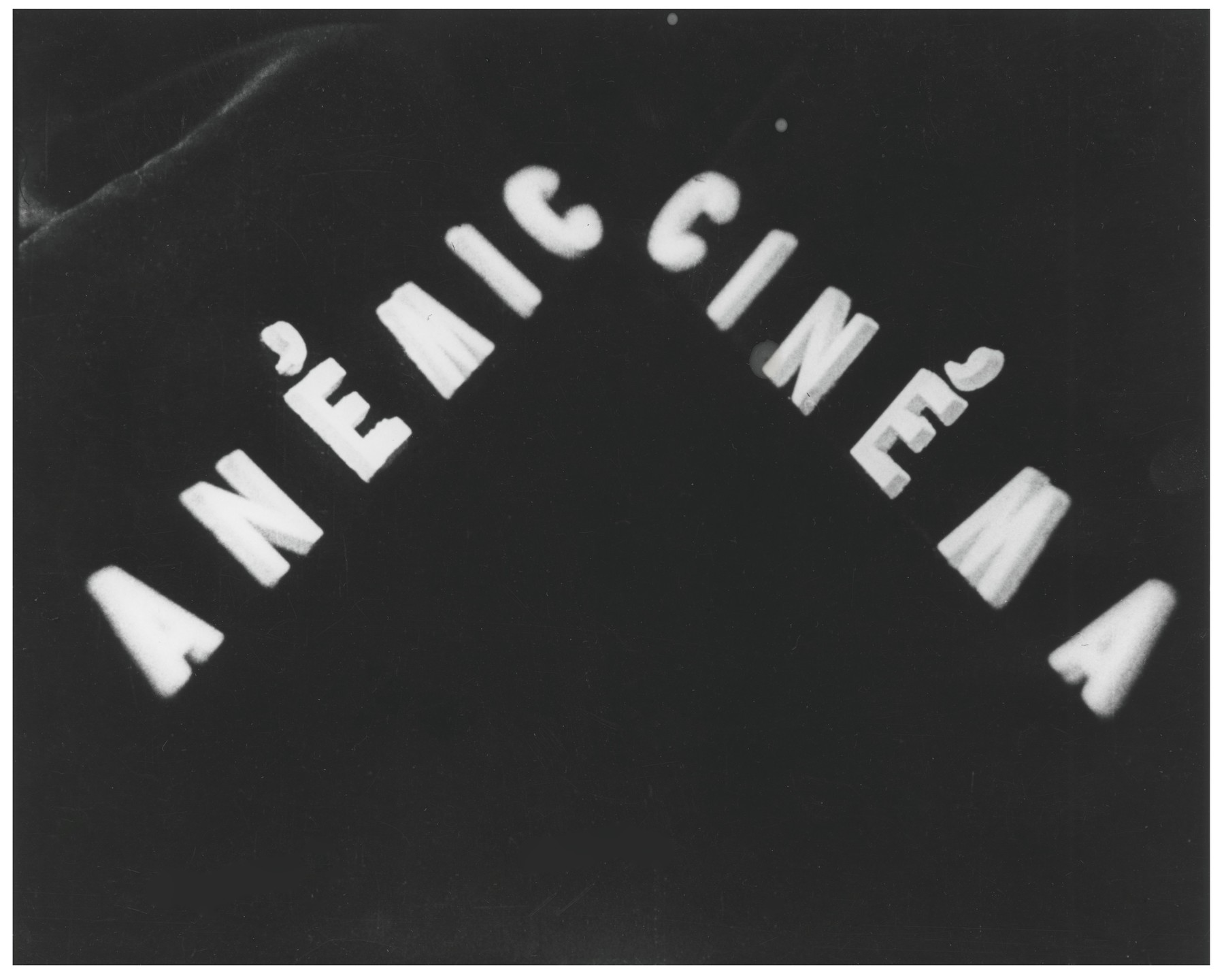

Duchamp’s new venture led to a six-minute film titled Anemic Cinema. Created in collaboration with Surrealist photographer and filmmaker Man Ray and the screenwriter and director Marc Allegret, Anemic Cinema alternates between whirling Rotoreliefs and French puns. Punning was a passion of Duchamp’s, one he explored through his female alter ego Rrose Selavy (Eros, c’est la vie, loosely translated as ‘Eros, such is life’).

While the puns are untranslatable into English, the simplicity of the film is recognisable by all. Focusing on shapes and image, and the effect of words rather than words themselves, Duchamp brought his ideas about conceptual art to film. Anemic Cinema is a film about the mind rather than about art or the meaning behind art. The apparent meaningless of the film is exactly what Duchamp intended; film as a thought process rather than as a complete, polished piece of work.

The Dadaists, of whom Duchamp was an idol, and later on the Surrealists, worked steadfastly within the anti-art realm. While their progressions and discoveries are now largely forgotten in favour of the perfectly conceived and the perfectly executed, their rebellious vision paved the way for new forms of art and a new freedom within artistic creation. Thanks to Duchamp, we now truly do accept anything as art, much to the confusion of failed art students and the trouble of creating an artistic ‘syllabus’.

By translating anti-art into anti-film, we are faced with new possibilities in terms of storytelling and the use or non-use of dialogue. If we re-embrace the surrealist vision of unbarred opportunity and creative simplicity, we can break out of the Hollywood formula.

Subscribe to FIB’s Weekly Alchemy Report for your weekly dose of music, fashion and pop culture news!