When can we consider extreme violence or explicit content in films necessary rather than a cheap source of thrills?

Gaspar Noe’s 2002 film Irreversible can be considered one of the most brutal films of all time. Unbroken takes of extreme violence and assault confront the audience with visions of a terrifying underworld and the depravity of human behaviour. Critics have described the film as a part of the cinema du corps or ‘cinema of the body’ canon, and as a part of the New French Extremity movement due to its nihilistic despair and confrontational subject matter. But can we justify these kinds of films by simply lumping them together as a movement, or are we excusing lazy filmmaking?

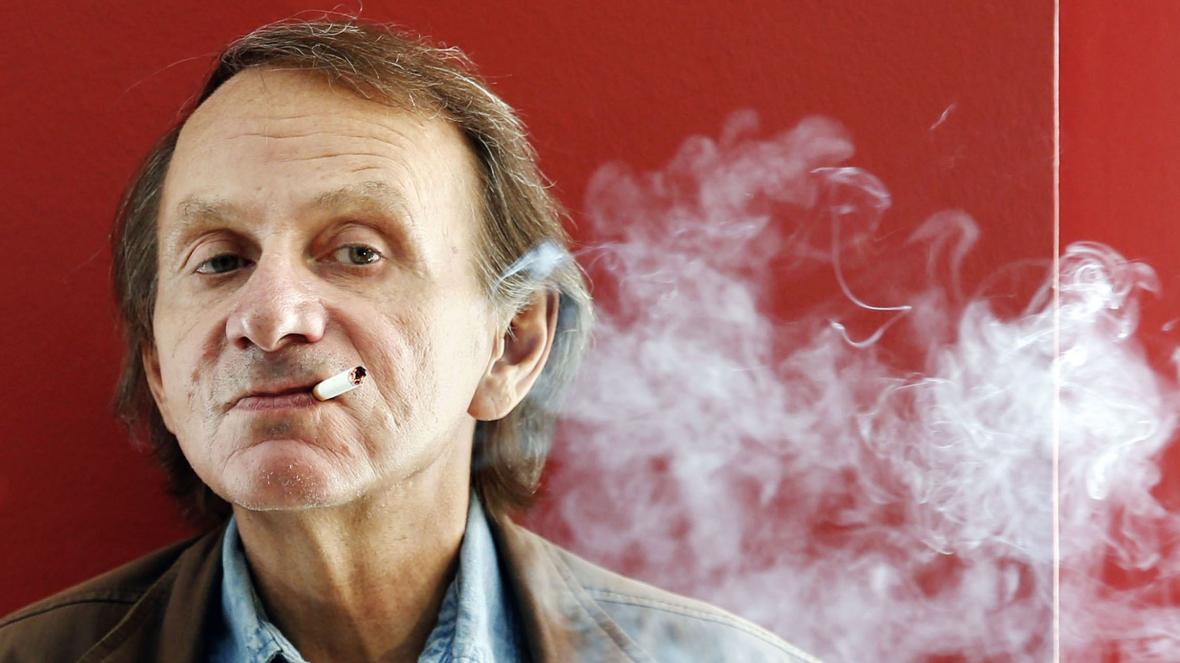

What makes extreme violence necessary? Certainly it works to shock the viewer, but filmmakers and artists have known this for many years. Most of Gaspar Noe’s films feature transgressive or taboo content, a trait he has come to be recognised by and criticised for. Many other filmmakers, such as Lars Von Trier, Pier Pasolini, even to a tamer extent Quentin Tarantino, have become recognised for their depictions of extremes in films. Writers too, such as French philosopher Georges Bataille or novelist Michel Houellebecq, have utilised themes of extremity and the limits of human behaviour in their works. But there comes a time when we must ask what the true reason is behind these kinds of ideas.

Michel Houellebecq’s novels often feature ageing, pathetic men descending into depravity and despair. This is done for comedic value, as Houellebecq pokes fun at not only himself but at the stereotype of the older caucasian male. Alternatively, Elem Klimov’s 1985 Soviet War film Come and See is graphic in its storytelling as it aims to depict the horrific truth of war crimes. These and similar works have clear, obvious explanations behind their explorations of extremes. Yet, many works of extremity seem unjustified, and are simultaneously criticised and praised for their ferocity.

The fact we as an audience, and subsequently as artists, know that extreme violence and confrontational subject matter will cause a reaction, means that we should seek alternative ways of causing these reactions. Isn’t it harder to make the viewer feel delighted than disgusted? Any film student or aspiring author can conjure up a world of horror and filth, but if they don’t seek to evoke feelings just as strong through themes of joy and understanding, won’t shock value be all we have left?

There is an inspiring moment in The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness, a 2013 documentary film tracing Japanese production studio Studio Ghibli and its mastermind Hayao Miyazaki. A team of young computer programmers are explaining new technology to Miyazaki. They show him a short clip of a grotesque creature they have animated, stumbling through a computer generated landscape on four legs, deformed and hideous. Miyazaki, a humble, old-fashioned man, loses his temper, and accuses the team of disrespect towards disability and a fascination for what is horrible and confronting. He is unimpressed. Miyazaki’s films explore the relationship between mankind and nature, and feature strong, independent female protagonists who strive for beauty and happiness. His success with these films show true strength of character and a genuinely original artistry. This, surely, requires more talent than whatever is immediately provocative.

Subscribe to FIB’s Weekly Alchemy Report for your weekly dose of music, fashion and pop culture news!