Ever since the 1800’s, visual media has been prey to product placement and ingrained advertisements, an ever evolving technique that has adapted to our modern viewing habits.

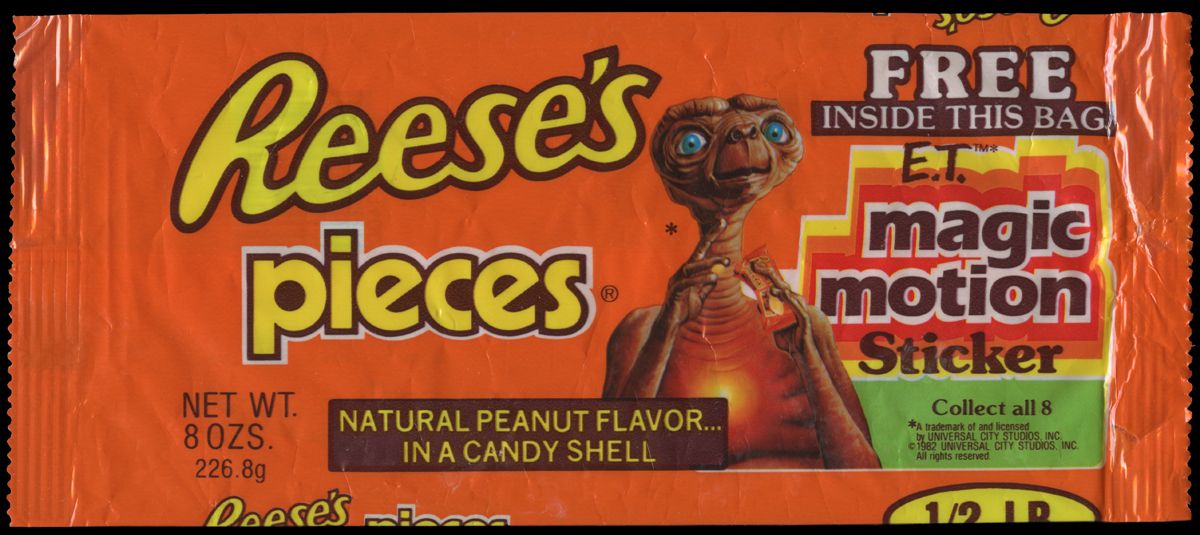

It seems only when we get older that we notice the texture of the wool over our eyes. As children, things either wash completely over us, or are absorbed into our minds, coming back later to make us re-think what we have been exposed to. Take Steven Spielberg’s 1982 film E.T the Extra-Terrestrial. In the film, the protagonist lures his new alien friend to him by leaving a trail of ‘Reese’s Pieces’, an American chocolate filled with peanut butter. To most viewers at the time, this slots in perfectly to the story, and while it might be amusing we don’t give it a second thought. However, beneath the surface was a million dollar cross-promotional deal that resulted in a 65% profit growth for the chocolate manufacturers.

Though the scale of these shady deals and the figures involved undoubtedly grew as both filmmakers and agencies became more cocky with their product placement, the idea itself was not new. An 1882 painting by French modernist artist Édouard Manet titled A Bar At The Folies-Bergère depicts distinct bottles at the bar of a cafe, clear enough to be identified as Bass Beer. Similarly, seminal writer Jules Verne’s 1873 novel Around The World In Eighty Days had transport and shipping companies requesting to be included in the story. With both these early examples, we can’t be sure that the artists were paid to include brands or brand names in their work, but they exemplify the initial desire for consumerist companies to expand their outreach through advertising in works of art.

While literature, art and assuredly magazines have been involved in product placement since their very inception, cinema attracted advertising potential from the beginning. The Lumière Brothers, by all accounts the pioneers and inventors of cinema, included Sunlight Soap in their earliest films, which were reportedly made at the request of a large manufacturing company. Many consider this the first example of paid product placement in film, an idea that has grown, adapted to and by some extent even led, the history of cinema up to today.

However, as long as product placement has existed in cinema, cinema critics have existed to condemn it. 1920 comedy film The Garage, the last film to feature the team of Fatty Arbuckle and Buster Keaton, includes numerous scenes where ‘Red Crown’ gasoline is at the forefront of the action. This led New York journal ‘Harrison’s Reports’ to criticise the film and state, “exhibitors of Los Angeles might ask Mr. Arbuckle how much he received for advertising Red Crown gasoline”, before condemning the product placement by adding, “if he states it was an oversight, it would be well to caution him to avoid such oversights in the future.” From the very beginning, then, critics and viewers noticed and were irritated by product placement. However, this did not stop the idea from growing.

Legendary German expressionist filmmaker Fritz Lang was unapologetic about his product placement. His 1922 film Dr. Mabuse the Gambler opens with a title card advertising and naming the costume manufacturers, while his 1931 thriller M advertises Wrigley’s Chewing Gum for a full thirty seconds. Through the next few decades, product placement in cinema became more and more frequent, used both to comedic effect such as in 1932’s Horse Feathers when a drowning woman is thrown a packet of Life Savers, as well as more subtly in other films, whether it be characters running across billboards or even momentary close-ups of products slotted in between sequences.

Despite product placement being called out by numerous reviewers and critics, filmmakers didn’t stop, and still don’t stop, signing deals with large corporations for fairly incredible sums of money. Tom Hanks plays a Fed-Ex employee surrounded by Fed-Ex boxes in Castaway, and befriends a Wilson Sporting Goods brand volleyball which he names, and thus repeats many times throughout the film, Wilson. The 2013 film The Internship is based on the premise that Google is a wonderful company which it would be a dream to work for. Tom Cruise wears Ray-Ban sunglasses in the 1983 film Risky Business. This resulted in 360,000 units sold. To the viewer, the sunglasses look great and remind us of a film we enjoyed, so we buy them, unaware Ray-Ban signed a contract in 1982 to pay $50,000 a year to a product placement company ensuring that their glasses were worn in film and television.

An issue often raised around product placement is the invasion of advertisement into art. However, some critics argue that the two have always been connected, and early examples of films and advertisement are somewhat interchangeable. The earliest days of cinema were not narrative-driven, and were often called ‘cinematic attractions’ or ‘fairground attractions’, enjoyed for their visual effects rather than any sort of storytelling. These early one or two minute cinematic experiments formed the basis for what we now know as television advertisements; simple, short explorations of a single idea, in this case a brand. This has become even more important in the modern world. As most ads we see can be skipped or ignored, companies have taken to blurring the lines of advertisement and entertainment even further.

Though this blurring of lines may have been popular in the early days of cinema, we now recognise an advertisement as an advertisement. However, filmmakers and corporations have become smarter with how they slot them into films. Most of us, on first viewing, simply see the fact that Tom Hanks is a Fed-Ex employee as a part of his character, that Reese’s Pieces just happen to be what E.T likes to eat. It is only on looking back at films from our childhood that we see just how infiltrated the cinematic world has become, and how easily they slip subliminal messages into our minds to make us obsess over brands and products.

The main issue around the idea of product placement is the question of ethics. An advertisement is one thing; irritating, but obviously reaching out to get you to buy a product or service without pretending to be anything else. However, trying to subliminally or subtly influence viewers with product placement in films, whether it be from what a character is wearing or even in the action of the film, could be considered dishonest. Furthermore, the ridiculous amount of money that goes into some of these deals betrays the hidden ambitions of these brands; lots of money paid to make even more money back, without regard to the genuine needs of the broader public.

These high sums can cause controversy in the film industry, with many filmmakers being considered sell-outs for taking these deals. There have also been instances where the creative freedom necessary to make a film has been compromised by a brand deal, resulting in legal disputes. This occurred with the 1996 film Jerry Maguire, starring Tom Cruise, Renée Zellweger and Cuba Gooding Jr. Sportswear manufacturing giant Reebok allegedly gave distribution company TriStar Pictures over $1.5 million for their promotion in the film. Gooding Jr.’s character holds a grudge against Reebok in the picture after striving for their support and being ignored. It was agreed upon that, at the end of the film, a Reebok commercial would play showing the character and his eventual success with Reebok. However, this commercial was cut from the final edit, and there are even multiple tirades against Reebok throughout the film, so much so that a representative claimed it was a though the film were ‘scripted by Nike’. When the film was screened without the commercial, Reebok launched a multi-million dollar lawsuit against TriStar for reneging on their agreement to portray Reebok positively. The filmmakers eventually settled outside of court, and included the commercial when the film was released on television.

Perhaps because of the risk of product placement deals going wrong, many manufacturers reach non-financial agreements with production companies to provide mutual amounts of advertising and promotion. Whether or not money has changed hands, however, does not detract from the sketchy and questionable ethics of both production companies and corporate brands agreeing to push a product in a work of art, especially when it is so embedded as to only be revealed to us upon pondering the film later. The 1992 comedy Wayne’s World parodies the obnoxiousness of product placement perfectly, with Pizza Hut, Pepsi, Reebok and Doritos all being advertised within a minute, Dana Carvey saying:

“It’s like people only do things because they get paid, and that’s just really sad.”

Subscribe to FIB’s Weekly Alchemy Report for your weekly dose of music, fashion and pop culture news!