Steven Spielberg invented the blockbuster, but what kind of terror hath he wrought in its wake?

There was a time when any new film from Steven Spielberg was not only a global event but one that rewarded all of us after our breathless anticipation. He took some of the most cinematic of subjects (aliens, dinosaurs, ghosts… shaaaaaark!) and made accessible movies that appealed to all ages because the stories were original and the characters were rich, giving each Spielberg movie the distinctive heart and soul that ensures their classic status decades later.

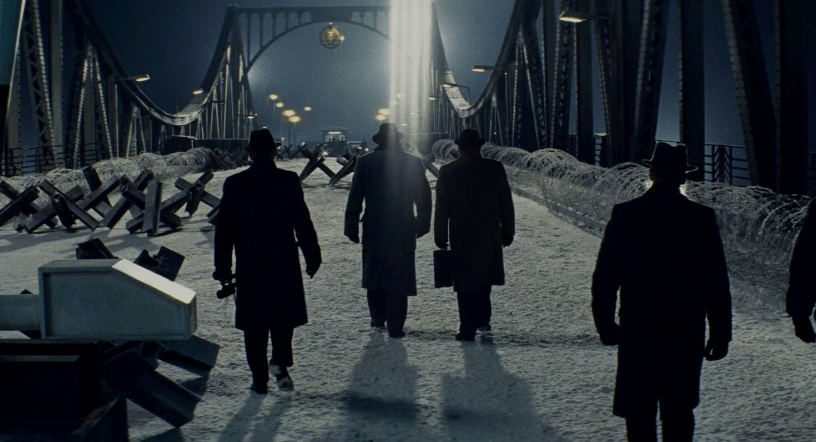

Spielberg’s movie, Bridge of Spies, looks kind of… stuffy. Gone is the child-like, wide-eyed wonder – Bridge of Spies looks like a perfectly workable but hardly inspirational Cold War spy thriller. Did he just grow up, or has Hollywood killed off the kind of blockbusters he used to be synonymous with?

Blockbuster cinema has morphed into a soulless, clanging gallery of CGI, thin characters and endless marketing tie-ins that just make cynics of us all. When studios invest more in animation software than stories and writers, try to spread the cost by enlisting armies of licensing partners and product placement, no wonder the results are getting blander.

A graph of the average Rotten Tomatoes scores shows a gradual decline over time since 1910. Sure, there’s a little bias – we tend to only remember the good movies from the antiquity of the pre-web age.

You also don’t need to be an industry insider to see Hollywood’s increasingly out of ideas. In 1981, two of the top grossing 10 films in 1981 were sequels. In 2011 eight of them were.

Ironically Spielberg himself helped instigate this decline. With contemporaries like George Lucas and Bob Zemeckis, he returned movies to big profitability after the creatively and financially dour 1970s by tapping into a market Hollywood hadn’t tapped into in such numbers before that – teenagers and young adults.

At the same time, the studios were all bought up by mega-corporations who put finance rather than creative people in charge. Their job wasn’t art, it was to chase the kind of money blockbusters like Jaws and Star Wars raked in, and they’ve been chasing it ever since.

The result is that next year, between Warcraft (March 11) and Pete’s Dragon (August 12) 34 films will be released carry big performance expectations, an average of one every four and a half days.

That makes the big screens of summer a constant parade of sound and fury signifying nothing, the quality of which seems to fall farther every year. Even the last two popcorn-fuelled blockbusters Spielberg himself made were underwhelming. Comments by critics about The Adventures of Tintin (‘fun and colorful, but it doesn’t have that creative explosion needed’) and Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (‘a colossal disappointment by any measure’) were never levelled at Jaws, ET or Jurassic Park.

The blockbuster business model itself isn’t a bad thing – a few monster hits usually comprise around 5 percent of a studio’s output but can earn up to 80 percent of its entire annual revenue. If you’re going to bet the farm on a handful of projects, it helps if they return your investment.

That means names that sell themselves like Harry Potter, Marvel, Star Wars or Pixar are the new brands, and they make more money than the old star system names like Tom Cruise or Jim Carrey ever did.

That’s doubly important considering how much these things cost to market. Kevin Smith took his 2011 film Red State on the road from city to city, old-style, because a traditional distributor would have needed to spend about $20m just to get the word out about a film that cost only $4m to begin with. A studio can easily spend $100m marketing a $200m film (which explains the curious phenomenon of movies making half a billion dollars these days and still being considered financial disappointments).

More expensive also means the films’ content is increasingly homogenised to appeal to cultural sensibilities in ever-more international markets. After overtaking Japan as the second biggest audience outside the US, China is a particular focus in Hollywood today, and getting the approval of the notoriously opaque state film authorities means self-censoring any number of controversial plots or characters. The 2011 Red Dawn remake was reedited after filming to make the villainous invaders North Korean rather than Chinese.

But if you can’t stand one more videogame-and-lunchbox ad masquerading as legitimate art, there are still gems on big screens. Although it’s long dead now, in the 1980s the home video market was so lucrative it represented up to 50 percent of a movie’s total revenue. It launched a whole industry of low-level production companies that made a fortune in straight-to-video genre films, many of them and their progeny now behind the biggest names in movies for grown ups.

As the big studios concern themselves almost exclusively with the new style of blockbuster – based on a game or comic few adults are likely to be interested in, overstuffed with CGI effects and not too different from the last big event movie – it’s creating a quality vacuum those small and indie studios are rushing to fill up.

When 2014 came to a close, lots of critics were saying it had been the best year on screens since 1967 thanks to indie movies with creative vibrancy like The Grand Budapest Hotel, The Wolf of Wall Street, Whiplash and Boyhood.

Great movies exist, as they always have, if you can tune out the white noise of the New Blockbuster.

Subscribe to FIB’s Weekly Alchemy Report for your weekly dose of music, fashion and pop culture news!