Even though story was never going to be the selling point here, it needs to stand up in a 90 minute movie despite the attention-getting production style. It’s a detective story of sorts, with a cynic who spends his days drinking and arguing with strangers going on the trail of van Gogh’s last few months to figure out why he killed himself – or if he did.

Armand (Douglas Booth), is the layabout son of Postman Joseph (Chris O’Dowd), who’s still in possession of van Gogh’s last letter intended for his brother Theo. Like most of cultured Europe, Joseph is still hurt by van Gogh’s sudden and senseless suicide in the fields near Auvers-sur-Oise, so he asks Armand to deliver the letter in person to somehow give everyone closure about the loss.

Reluctant about the mission but with nothing better to do, Armand travels to Paris only to learn that Theo himself died only six months after his brother, but he tracks down an art dealer who used to supply van Gogh with materials. He suggests Armand travel to the village where the artist spent the last few months of his life and talk to the doctor who treated him when he was released from a nearby asylum and who became his patron and friend.

Armand finds himself installed in the same guest house where van Gogh stayed while he waits for contact from the artists’ friends and acquaintances in the area. He quickly strikes up a friendship with the bubbly innkeeper, Adeline (Eleanor Tomlinson), who takes an interest in his quest and tells him everything she remembers about the inn’s most famous resident.

While waiting to meet the doctor he comes across several other locals. A boatman who rents out rowing boats by the picturesque river points him in the direction of the doctor’s repressed daughter Marguerite (Saoirse Ronan). At first she’s prickly and dismissive, outright rejecting the boatman’s story about an argument between van Gogh and her father and the role it might have played in his death.

At the same time, Armand gets wind of a local lad who apparently carries a gun (not very common in late 1800s rural France) and used to tease van Gogh for his sensitive, quiet nature. Then there’s the doctor who inspected van Gogh while the latter lay in his bead mortally wounded, who now says the bullet came from too far away to be self inflicted, all combining to make Armand wonder if he’s onto a murder mystery.

It’s engaging enough even though it asks more questions that it answers, and you wonder how much of the characters and their relationships to van Gogh are historical fact rather than fancies of the writers Dorota Kobiela, Hugh Welchman (who co-directs) and Jacek Dehnel.

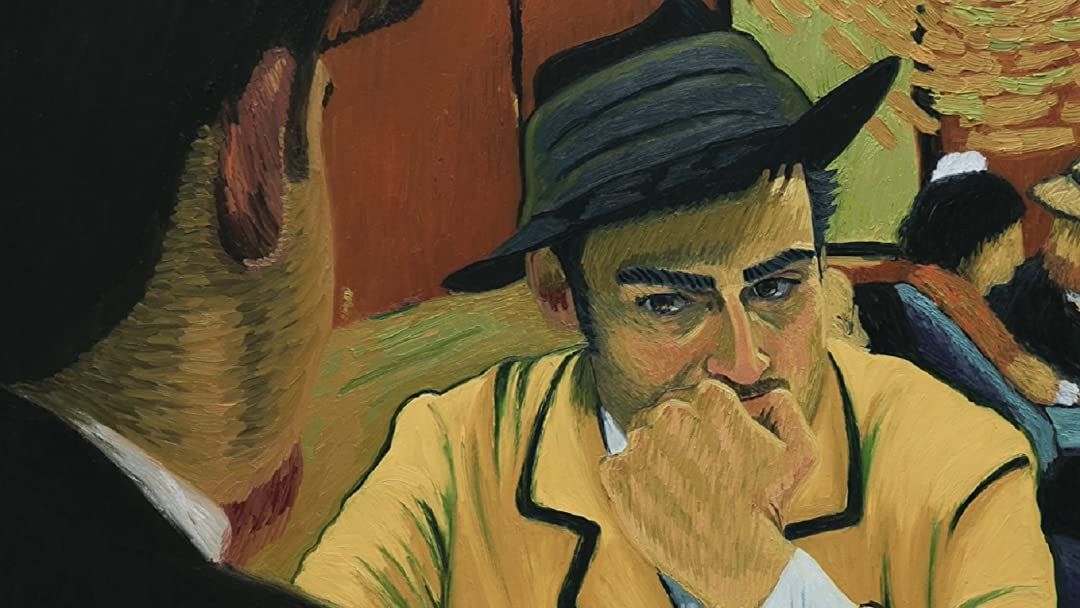

But as the marketing at the time promised you, the story isn’t the USP. Using a team of over 100 artists, every frame in the film is hand painted. What’s more, they’re all done so using van Gogh’s styles and signature form as inspiration.

It’s quite eye popping for the first few minutes as you notice it, but like every element in movies from special effects to music should do, you stop consciously noticing it before long, letting it do its job as part of the milieu of a tale being told.

But the production process of how they had the actors give their performances, animate them into backdrops with van Gogh’s style, then produce frames which were then painted as original oil paintings is fascinating.

The result is something like the acclaim you always hear attributed to Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon, with the background and foreground in focus as the same time. It means Loving Vincent is missing the deep depth of field you expect from real life – especially of lush wheatfields in an idyllic small town in a European summer – and it renders the whole movie kind of flat. But instead of making it feel constrained and televisual, here it just feels like a painting exactly as the directors intended, and it’s a very different movie watching experience as a result.

Subscribe to FIB’s Weekly Alchemy Report for your weekly dose of music, fashion and pop culture news!