Yukio Mishima’s 1966 short film grimly predicted the end of the legendary Japanese author’s own life.

Yukio Mishima was a true renaissance man. In his 45 years on earth he wrote numerous novels, short stories and poetry collections, directed and starred in films, worked as a model and was actively involved in Japanese politics. He is now widely considered as one of the most important Japanese authors of all time. To no small extent he introduced extreme ideas of eroticism and death through stylistic prose into Japanese culture, and created works that expertly blended his passion for traditional Japanese values with modern artistic trends.

Mishima began life in a difficult household. His father was a military man who discouraged his son’s literary ambitions as ‘effeminate’, and would hold the young boy up to the side of speeding trains to encourage his strength. He spent a lot of time with his grandmother, a woman with traditional Japanese values and Imperial heritage. She introduced the young Mishima to kabuki and noh theatre, but was also overly protective and kept her grandson inside to play with dolls and female cousins. This confusion of masculinity and femininity stayed with Mishima throughout his life, as did the mix of traditional and modern ideas which were later to inform his work.

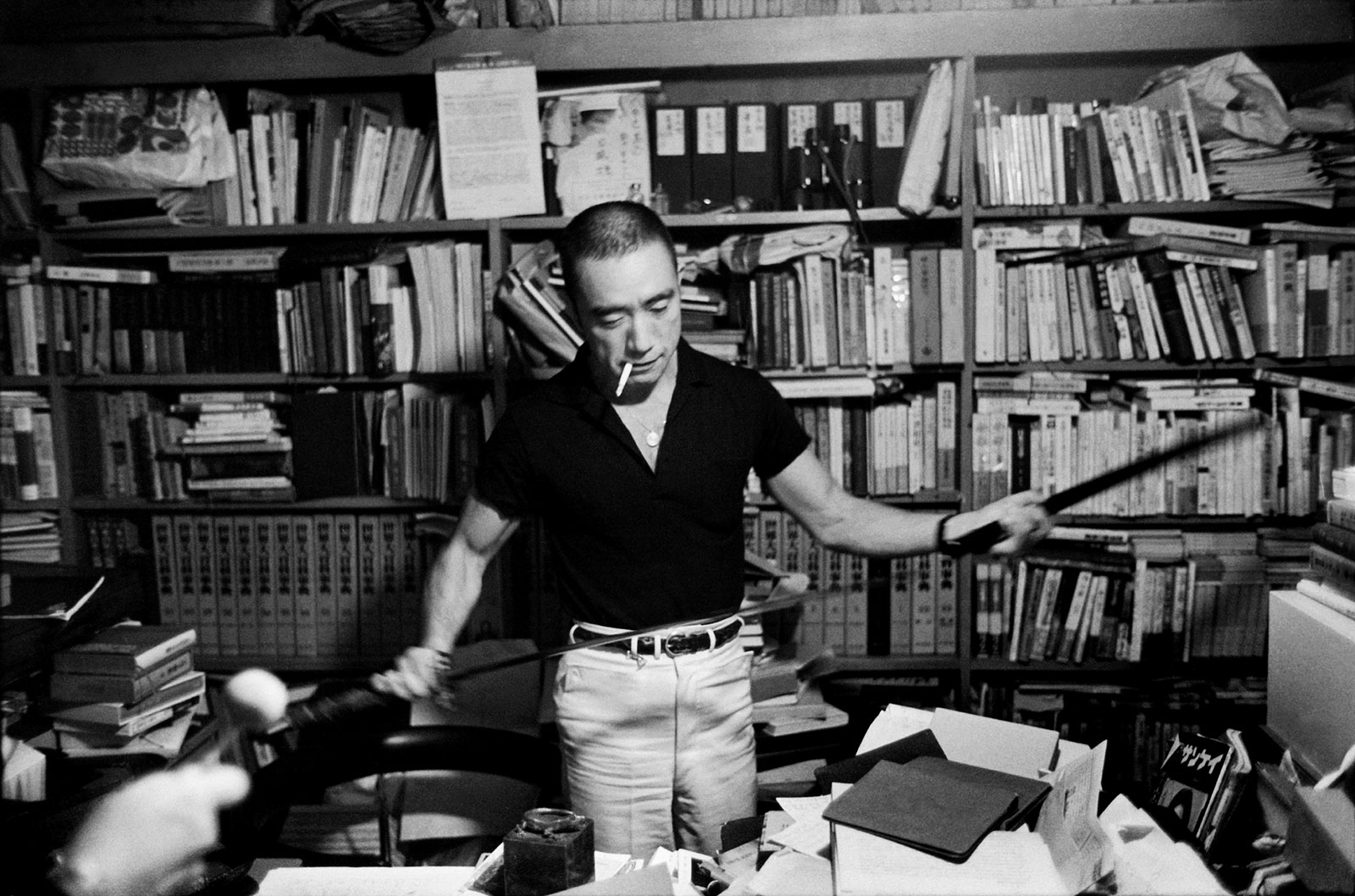

Writing in secret and using a pen name to hide his work from his father, Mishima first found success in literary magazines. He became internationally recognised for his novel Confessions of a Mask about a young gay boy who has to hide his true self from society and finds release in the relationship between eroticism and violence. Mishima’s subsequent works were translated into many languages, and he spent many productive years writing novels and plays. He also became increasingly interested in bodybuilding and wrote an autobiographical essay, Sun and Steel, rallying against the artistic notion of the importance of the mind over the body. He maintained his routine of three intense workout sessions a week for fifteen years. He also modelled during this time, many photographs being captured of Mishima demonstrating his fascination with samurai tradition.

For Yukio Mishima more so than many authors, the pen and the sword could not be separated, and one was as mighty as the other. As he became more interested in politics, Mishima took a traditional, right-wing attitude towards Japanese culture. He deplored Communism and the Cultural Revolution and wrote polemic attacks against these sorts of left-leaning ideas. Over time he gained a reputation not only for his works but for his outspoken views, and became the subject of much hatred from left-wing politicians and society. Mishima was committed to the idea of bushido, a set of ideals based around honour and tradition that constitute the way of the samurai. He also believed passionately in the idea of an Emperor. Both these views were becoming outdated and dismissed by modern Japan as archaic. As he was in his childhood, Mishima found himself once again criticised for who he was.

The idea of seppuku was one of extreme interest to Mishima. Seppuku, also called harakiri, is a ritual death by disembowelment. It was first used by samurai in order to die with honour rather than fall into the hands of their enemies, but was also adopted by other Japanese people in relation to honour around family. Mishima’s fascination with death, which he had had since a child, was realised in the idea of seppuku, marrying his interests in violence with his traditional values and reverence for the samurai lifestyle.

Mishima explored his interest in seppuku in his 1966 short film titled Patriotism, the Rite of Love and Death. Based on Mishima’s own short story, Patriotism follows a Lieutenant, played by Mishima himself, and his wife immediately following a failed coup d’état. The plot is loosely based on the Ni Ni Roku Incident which took place on the 26th of February 1936 in Japan, where failed rebels killed themselves after surrendering. The Lieutenant in Patriotism has been forced to assassinate his fellow rebels and decides to perform seppuku out of shame and failure. His wife, in Shakespearean fashion, decides to do the same.

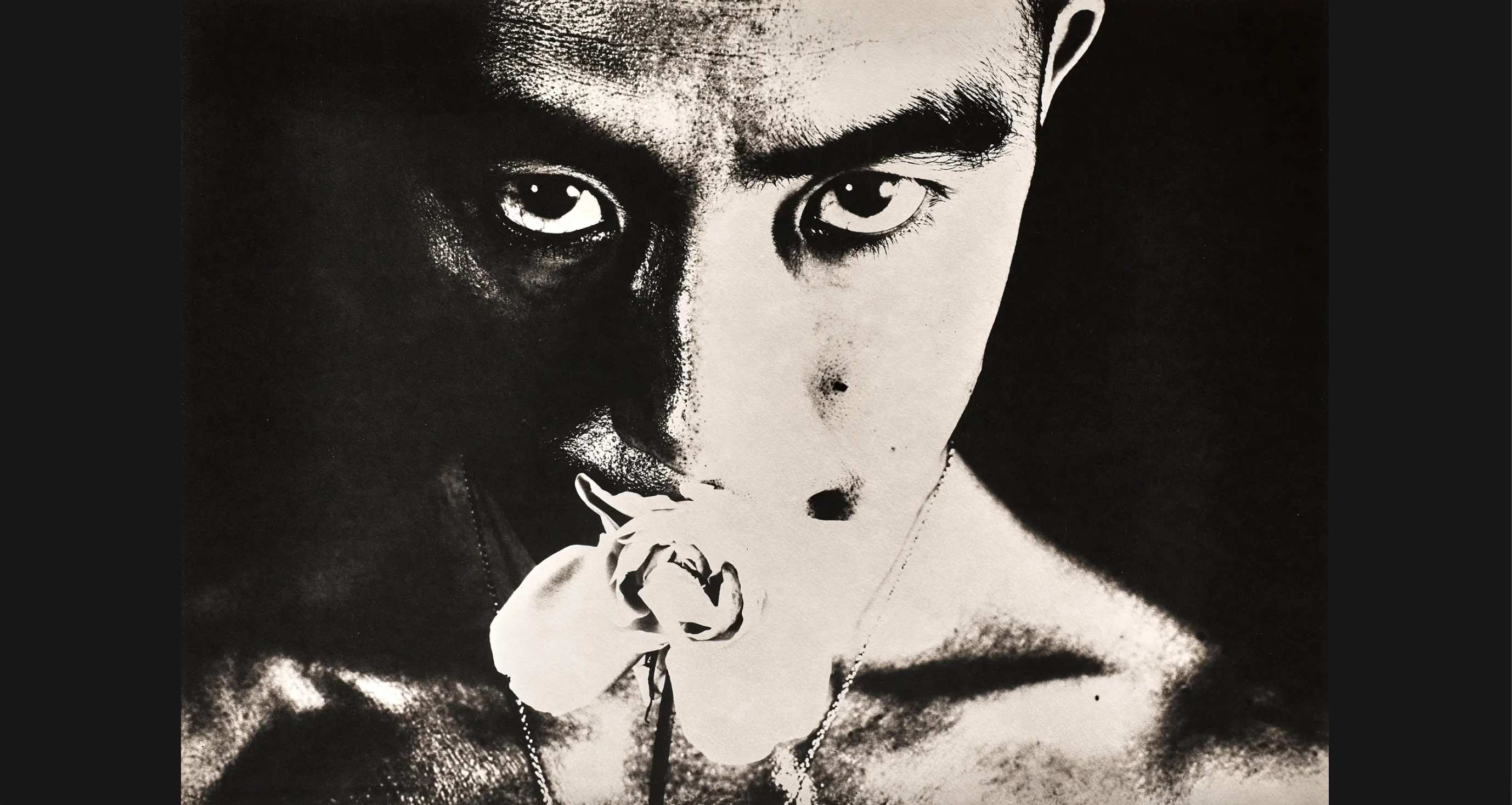

Though dealing with such strong and dramatic subject matter, the film is simple in its execution. Running for less than thirty minutes, wide-angle shots of a sparse room in which the couple make love and die are permeated by close-ups of their eyes. When in military garb, Mishima’s eyes are darkened by the brim of his cap, while his wife’s remain glowing and focused on her husband. In the intimate parts of the film Mishima’s eyes glimmer with the same love, as the two sleep together for the final time. The simple cinematography and elegant set design serve to dramatise the brief events, making Mishima’s disembowelling in all its bloodiness and gore all the more shocking.

Patriotism does not shy from the truth. The scenes of ritual death are visceral and shown in close-up. It is a blessing the film is black-and-white or the events might be too gory to tolerate. This sits in line with Mishima’s obsessions about the intricacies of death, his fascination with precision and aesthetic beauty in all aspects of life and its ending.

Four years after the release of Patriotism, Mishima and a group he founded called Tatenokai consisting of politically likeminded men, barricaded themselves in the Tokyo office of the Japanese Self-Defence Force. Mishima addressed a crowd of soldiers from the balcony in this attempted coup d’état, hoping to restore power to the Emperor. He was mocked and laughed at. Immediately after re-entering the building, Mishima committed seppuku.

It seems too coincidental to be dismissed as random. Biographers argue that Mishima’s uprising and attempted government overthrow was merely an excuse for him to die the way he had dreamed of. Evidence shows he had planned his death by seppuku for many months, organising his affairs and finances and only informing the members of Tatenokai of his plans. He wanted to live out his own creation, and fulfil not only a tradition but a fiction.

Yukio Mishima’s legacy lives in a difficult middle ground. Though he is considered an LBGTQI icon and is an honouree in the Rainbow Honour Walk in Los Angeles, he held cultural and political views that would be considered nationalist and intolerant in modern ways of thinking. His books, though beautifully written and poetically constructed, are often baffling in their message, and seem morbidly obsessed with the darker sides of humanity. Yet anyone interested in Japanese literature, film or culture in general can learn from Mishima about both traditional and modern Japan, presented to us in the strange but wonderful story of his life.

Subscribe to FIB’s Weekly Alchemy Report for your weekly dose of music, fashion, and pop culture news!