Kawakubo has always asserted she owns a duality of personality, and her early adult years did much to cultivate this notion: while the bohemian lifestyle of Harajuku spoke to her inherent desire to “break the rules,” the other half – gifted through education and the affluent social circles she formed during university – held a deep concern for both “tradition and history.” This dichotomy would eventually be shown through her sense of design; an appreciation for traditional Japanese construction undercut by a desire to invert traditional ideals of fashion for the sake of shock.

To support her new lifestyle Kawakubo found a job in the advertising department of Asahi Kasei, a textile manufacturer. She was afforded an uncommon amount of leeway in her new position, refusing to wear the standard uniform of an office girl and assisting in photo shoots by finding props and sourcing costumes. She held a significant talent for the latter; eventually, one of her colleagues insisted Kawakubo become a freelance stylist, a rarity for the time. When she couldn’t find the appropriate clothes for her assignments, despite a lack of formal sartorial training Kawakubo began to design her own.

By 1969, two years after joining Asahi Kasei, she was confident enough in her skills she began designing under her own label: Comme Des Garçons, French for “like some boys.” After a few successful years selling her designs in local stores, she incorporated the label in 1973; two years later she opened her first boutique in Tokyo.

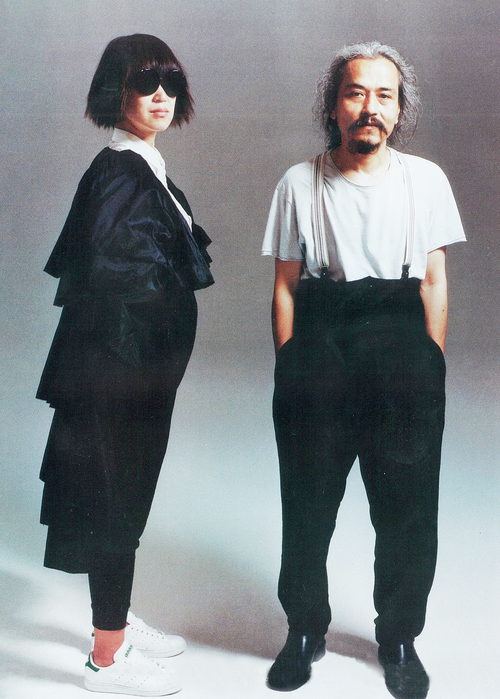

It was around this time Kawakubo became romantically involved with fellow Japanese designer Yohji Yamamoto. They were alumni of the same university and creatively likeminded, producing clothing that challenged traditional concepts of beauty – dark, over-sized, asymmetrical garments that failed to adapt to the contours of the human body.

Although they never collaborated, they were close traveling companions who made their international debut the same year and, along with Issey Miyake, were tagged together as renegade Japanese designers determined to push Western conventions. Not that Kawakubo ever appreciated the comparison: “I’m not very happy to be classified as another Japanese designer,” she remarked in 1983. “There is no one characteristic that all Japanese designers have.”

Happiness was an elusive characteristic for Kawakubo. She rarely smiles, holds disdain for the social convention of small talk, and by her own admission is “more or less always angry.” It’s a bitter melancholy reflected in even the earliest of her designs: the jagged, fraying edges of her asymmetrical garments textured in her signature black tone; so often used to appear slimming and beautiful in Western culture, in the hands of Kawakubo it signals an emptiness within fashion – absence, rather than presence. Even as she expanded into colour later in her career, believing the tone to be tired, black remained an integral feature of Comme Des Garçons through her “Noir” line.

Kawakubo developed as a designer over the next decade. She became fascinated with the imperfection; in her eyes, “perfection was the devil,” and like the Japanese temples of old her garments remained unfinished to resist such temptation. Her preoccupation with asymmetrical shapes was born of an interest in modern architecture and the traditional flat, layered styling of the kimono; garments adhering to flexibility and comfort rather than the standard framing of the silhouette that defines orthodox Western beauty.

More than anything, the clothes of Comme Des Garçons represented attitude: the desire to find new and provoking concepts of fashion, to shock and upset the status quo through revolutionary design. They were almost anarchistic in their intent; indeed, the matriarch of rebellion, Vivienne Westwood, once described Kawakubo as “a punk at heart.”

By the late 1970s, Comme Des Garçons was one of the most influential, provocative labels in Japan and the greater East. She had added a men’s line in 1978 – Homme Comme Des Garçons – and developed a cult following of anti-fashion followers the Japanese press labelled as “crows.”

Despite her rampant popularity in the East, however, Kawakubo was still relatively unknown in the West. That all changed in the early 1980s. Comme Des Garçons debuted in Paris in 1981, turning heads with her deconstructed, flowing garments; but it was her offering the following year that summoned a storm of controversy and shook the conventions of Western fashion to its foundations – the aptly titled “Destroy” collection of 1982.

All black, militaristic and damn near apocalyptic, Destroy caused a furore amongst the Parisian press, who condemned the collection as “Hiroshima’s Revenge.” Models in furious war paint thundered down the runway to the incessant beat of war drums, draped in oversized garments, loosely knit and severed with holes seemingly slashed by a cabal of knives.

The fashion world was cleaved in two. While Kawakubo “never intended to start a revolution,” Destroy did exactly that: for every critic and high couture designer mortified by the collection, Comme Des Garçons found a convert – the avant-garde and individualists of society, who flocked to the Kawakubo anti-fashion like the crows of their namesake.

The 1980s were a time of rapid expanse for Comme Des Garçons. Her first Parisian boutique opened in 1983, along with a store in New York; by the late 1980s there were over 300 stores scattered across the globe, a fourth of which founded outside Japan.

In 1988 Kawakubo launched “Six,” a biannual magazine named for the sixth sense. The magazine replaced their traditional catalogue and concerned itself more with stream-of-consciousness and surrealist content than it was with fashion itself, focusing less on words in favour of illustrations, art and photography – including shots from notable photographers Bruce Weber and Peter Lindbergh.

Despite her cultural background and the insistence of many fans, Kawakubo insists her work has never been as an artist: “I have only continued all these years to try and make a business with creation … I cannot separate being a designer from being a businesswoman. It’s one and the same thing for me.”

Unsurprisingly, Kawakubo is as adept a businesswoman as she is a designer. Under the watchful eye of Kawakubo, Comme Des Garçons has grown to incredibly successful heights, an annual revenue of around $220 million – far outstripping her Japanese peers. She commands a near total control of her label: from deciding the sparse, industrialist design of her stores to the furnishings each one contains – even the way her employees are required to act and dress.

Yet there have been times Kawakubo has conceded she is, at the very least, a “businesswoman/artist.” Indeed, her creative process when envisioning a collection sounds less like a traditional designer and more like that of a conceptual artist. Although she goes to great lengths to avoid explaining herself, she has occasionally has divulged the her creative methods:

“My design process never starts or finishes. I am always hoping to find something through the mere act of living my daily life … often in each collection, there are three or so seeds of things that come together accidentally to form what appears to everyone else as a final product, but for me it is never ending.”

The dissimilarities between Kawakubo and her designer contemporaries extend beyond her process. While other fashion moguls indulge in mansion hopping, art collecting and socialising with celebrity elite, Kawakubo enjoys a quiet lifestyle dedicated to her work; her only indulgences, it seems, is her love of animals and the monstrous 1970s Mitsubishi car she drives through the streets of Japan.

Beyond this, Kawakubo leads a life of relative solitude. Few are close to her; fewer still have been granted access to her home, an apartment close to her business headquarters in the Aoyama shopping district of Tokyo. Even her husband – Comme Des Garçons CEO Adrian Joffe – lives removed, running the international wing of their company from the label’s headquarters in Paris.

Kawakubo and Joffe became an item in the early 1990s, after Kawakubo separated from former flame Yamamoto. After a short courtship the couple married in 1992; Joffe has since become CEO and personal translator for his wife, effectively handling any communiqué between Kawakubo and the outside world.

Despite his integral position within the company, no-one – not even Joffe himself – is under the illusion Comme Des Garcons is anything less than the domain of Kawakubo. This is, after all, the designer who once famously declared she creates clothes for the woman “who is not swayed by what her husband thinks.”

Kawakubo has relaxed the reins of her company in the last few decades however, allowing other designers to put their own unique spin on Comme Des Garçons style. Beginning with Junya Watanabe in the early 1990s, her stable now includes Tao Kurihara and most recently Kei Ninomiya, each of whom design for the brand under their own unique sub-labels.

Comme Des Garçons has unleashed over two-dozen lines since its inception in 1973, even consenting to create easier-to-wear subsidiaries like the Comme Des Garçons Comme Des Garçons range; they have collaborated with a host of diverse and established brands over the years, including Lacoste, Fred Perry, Nike and the exalted nobles of Parisian high couture, Louis Vuitton.

But those who believe the aggressively unique designer is softening in her old age may want to reconsider. Kawakubo is still capable of causing controversy when she so chooses; in fact, she seems to relish it.

In 1995, the presentation of her men’s collection “Sleep” – a series of baggy, striped pyjamas evocative of the prison uniforms worn in Auschwitz – created outrage for all the wrong reasons. The collection, stamped with “identification numbers” on each garments and displayed by models with shaved heads – was unveiled on the 50th anniversary of the holocaust.

It was an unintentional step too far for Kawakubo, who discontinued the line and released an official apology for her blunder. There would be no apologising two years later however, when the 1996 collection “Dress Meets Body” was unveiled and Kawakubo shocked the world once more.

Incensed by a Gap window displaying banal black clothes – her signature tone, reduced to something incomprehensibly generic – Kawakubo began experimenting with new forms of structure, inserting basketball-sized pads as a deformity intended to highlight the “actual” over the “natural.” By adding these extensions Kawakubo believed she could control the perception of reality, making deformity seem as conventional as the Gap blight that had inspired her designs. Critics of the collection were less convinced, declaring it a perversion of design that conjured nothing other than the “strange.”

Kawakubo has always been unafraid to reject progress and convention, even after embracing it. When her 2011 collection “White Drama” was too easily understood – its cryptic title easily deconstructed by critics as a journey through the seminal events of life – Kawakubo became despondent, later declaring she does “not feel happy when a collection is understood too well.”

It is a desire for the unique that permeates every facet of her business. In 2004, Kawakubo, together with Joffe and Comme Des Garçons, were credited with originating the pop-up store trend, introducing the label to cities around the globe for less than a year in any given location; once the idea entered the mainstream Kawakubo denounced the idea as tired and ceased producing pop-up stores.

A 2008 collaboration with H&M produced similar results. Despite its rampant popularity – the collection produced a near-riot in Tokyo – Kawakubo is reluctant to travel the same path again, going so far as to criticise the fashion industry outright:

“I don’t feel too excited about fashion today, more fearful that people don’t necessarily want or need strong new clothes, that there are not enough of us believing in the same thing, that there is kind of a burnout, that people just want cheap fast clothes and are happy to look like everyone else, that the flame of creation has gone a bit cold, that enthusiasm and passionate anger for change and rattling the status quo is weakening.”

Yet the “flame of creation,” as Kawakubo elegantly puts it, continues through the litany of high-profile designers she has influenced through her nearly five decades in fashion; European converts like John Galliano, Martin Margiela and Raf Simons – legendary designers enchanted by the anti-fashion that Kawakubo dragged into the consciousness of couture all those years ago.

And yet, Kawakubo is not done. The 72-year-old continues to work 12-hour days almost seven days a week, all in the name of finding the new; the provocative; the shocking. As difficult as it becomes in the modern era of fashion, when so many have injected themselves into the medium with the same deconstructionist aesthetic Kawakubo in part inspired, her aspirations to push the boundaries of fashion continue to delight and offend in equal measure.

Kawakubo wouldn’t want it any other way.

2 comments

Comments are closed.