The true crime story of Steven Avery that climaxed a decade ago has been paid due recognition by co-creators Laura Ricciardi and Moira Demos for its sheer enthralling and controversial nature. Now a phenomenon following its Netflix release last December, Making a Murderer has been constructed to spark debate by its filmmakers. But what debate exactly?

It is uncommon to see such frenzy circulate around a documentary series. The most comparable may be HBO’s series The Jinx which follows accused murderer Robert Durst, but Making A Murderer transcends to a higher level of success.

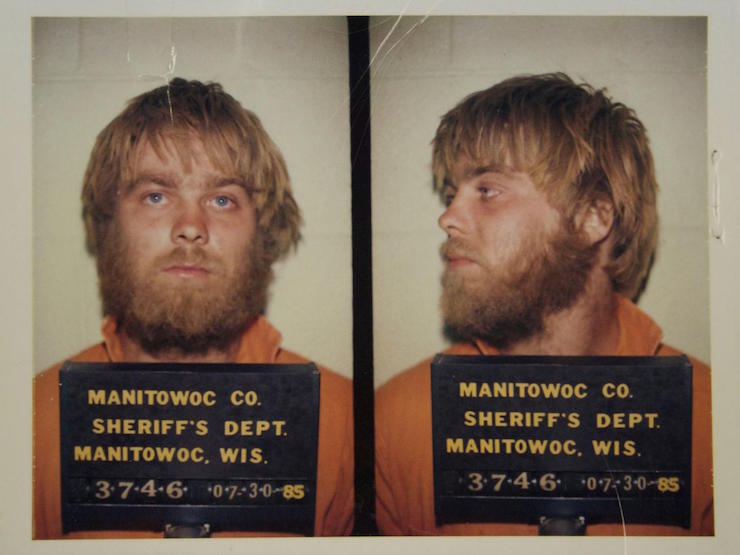

After learning of Steven Avery – an infamous Manitowoc County (Wisconsin) resident – and his most recent conviction (2005), film graduates Ricciardi and Demos set out over the next ten years to produce their own opinion on what this case really means to them.

credit: independent.co.uk

The series’ ten parts comprehensively follows a mind-wrenching journey, each episode unpacking more and more information apart of this saga. The first episode, “Eighteen Years Lost” is successful in presenting a thorough account of Avery’s early life up till his first conviction. In 1985, he is sentenced to thirty-two years in prison for the sexual assault and attempted murder of Penny Beernsten, eighteen of which are served before he is exonerated by DNA evidence. Avery became the poster boy for wrongful convictions and his case attracted widespread attention. The episode’s end presents the cliffhanger that triggers the debate for the rest of the series. What are the implications when one pursues legal action against the state? In Avery’s case, Ricciardi and Demos imply the question, did his thirty-six million dollar federal lawsuit against Manitowoc County pave the way for his doom?

“Turning the Tables” sets up the real meat of the series: the murder of Teresa Halbach. We learn that midst Avery’s depositions for his lawsuit (and just over a year after his exoneration), he is arrested for the murder of twenty-five year old photographer Teresa Halbach. The whodunit mystery grips the audience. On October 31, 2005, Halbach was scheduled to meet with Avery and take photographs of a car that resided on his Auto Salvage yard – Teresa is reported missing a few days later. After a two week search, Halbach’s car – with Avery’s blood in six spots – is found in the yard, as well as charred bone fragments unearthed in the fire pit behind his garage.

credit: thoughtcatalog.com

The debate comes into play after this evidence is unearthed. On the surface, one is torn between the conviction that Avery was framed for the murder by a corrupt police department who sought to put an end to his impending lawsuit, or, did he indeed commit the crime. Beneath this hype, the filmmakers are in reality, attempting to poke holes in the American criminal justice system, questioning the ethical and moral responsibilities of those in authoritative positions.

Making a Murderer triumphs in opening the viewer’s eyes to the potential inconsistencies and failures that lie within the justice system. As the episodes proceed, segments of Avery’s trial are shown – the prosecution and defence’s legislative game of ‘ping pong’ is truly compelling. The prosecution, led by Ken Kratz, covers the evidence against Avery in a melodramatic manner that fashions him unlikable to the audience. From the first minute of the series, we are also subliminally persuaded to take a disliking to the Manitowoc County Sheriff’s Department whose lack of due process was the reason Steven was wrongfully convicted in the Beernsten case. Ricciardi and Demos make it clear these same officials who were prohibited from searching the Avery property as a conflict of interest were responsible for discovering the evidence that incriminated him. Several other instances of potential tampering with evidence are raised, including a bullet fragment found in the garage and Avery’s opened blood vile.

The matter of Brendan Dassey becomes baffling for any viewer convinced of Steven Avery’s innocence. Avery’s nephew, a clearly learning disabled sixteen-year-old later confesses to the rape, murder and mutilation of Halbach perpetrated with his uncle. The video of his confession, between Dassey and two investigators, is disturbing as the skilled pair feed him the answers to their questions. His ‘confession’ is in no way convincing, yet, one cannot comprehend his motive to fabricate such a tale.

credit: hngn.com

Nonetheless, Ricciardi and Demos should not consider themselves entirely triumphant in developing a work that seeks impartiality and justice. Whilst it is easy to ride along with the filmmakers’ frame of mind, anyone reading between the lines can percept an overt bias – not necessarily for the Avery family, but against those with authoritative power. We do witness large segments of the trial, yet it has been noted that key evidence was excluded from the ten-part documentary: Avery’s DNA sweat found under the hood of Halbach’s car, his use of fake name and hidden phone number, and confession to a prison inmate regarding his desire to build a ’torture chamber’ upon his release are all factors omitted.

In a New York television interview, Kratz states:

“It’s not a documentary at all; it’s an advocacy piece”

Alternatively, Dean Strang, Avery’s defendant, told The Progressive that Ricciardi and Demos simply did not have time to include everything:

After ten hours of viewing this murder mystery, one is left puzzled. One episode affirms Avery’s innocence, the next his guilty. The filmmakers’ apparently bias should most definitely be questioned, but should not hinder the true objective of the series. This is a powerful story about the failure of justice. Whether Avery and Dassey are innocent or guilty is not the questione to be answered at the series’ conclusion; it is whether they received a fair trial in the court of law. Should we ignore inconsistencies in the face of the law? Is the law just? Does justice prevail?