FIB looks at why we should care about album writing credits and proposes a solution to the dilemma of artistry.

In the modern music landscape, with a simple internet search, we can uncover a plethora of detailed information about any song, album, and the artist. Web sites such as Genius allow for annotations of songs where an artist or a keen listener can provide interpretations of lyrics. We are also capable of knowing who was involved in the writing and production of a song.

This has heightened listeners ability to question ideas of artist authenticity and the purity of the artist. These ideas have led to considering if it matters and why it is a point of concern that a musician writes their own music.

Frank Ocean, notoriously private and perhaps the antithesis to the meticulously cultivated images of many mainstream pop artists, released his highly anticipated third album Blonde. The album included a guest verse from acclaimed musician André 3000 of the hip-hop duo Outkast. The song ‘Solo (Reprise)’ addressed the issue of ghost-writing in rap music saying,

“After 20 years in, I’m so naïve

I was under the impression

That everyone wrote they own verses

It’s comin’ back different and, yeah, that shit hurts me

I’m hummin’ and whistlin’ to those not deserving

I’ve stumbled and lived every word

Was I working just way too hard?”

This sparked controversy as to who these lines were directed. It was widely assumed that it was referring to Drake’s highly respected place in the industry while also using uncredited writers for his songs. While this verse was supposedly written long before Drake was outed, André in 2012 openly expressed his view on the debate of artistry saying, “In this day and age most rappers don’t even write their own raps, which is OK cause we love their albums.”

Artists frequently collaborate with each other to create amazing music, however when Justin Bieber releases a song that was written originally by Ed Sheeran, who do we consider the artist? The song wouldn’t be what it is without Justin Bieber’s interpretation but it wouldn’t exist at all without Ed Sheeran writing it and Benny Blanco producing it.

The requirement that a single artist must be responsible for their entire work relies on Great Man Theory. This reductive mythical style is littered in history, where we remember a single individual as the stand alone figure who enacted great change, in spite of being assisted by a much larger group of people in the reality of most circumstances. Steve Jobs didn’t create Apple alone in his dorm room, nor was Henry Thoreau entirely unaccompanied in his apparently isolated quests to return to completely to nature.

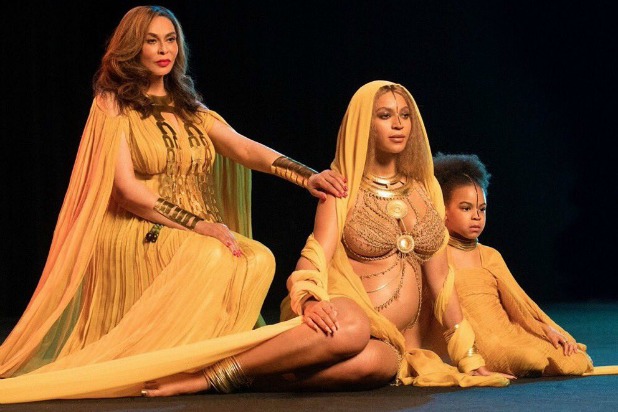

Beyoncé has also been criticized throughout her career for not having enough hand in the creation of her own music. This has been particularly noticed following the release of the writing credits for her incredibly successful Lemonade album which included 72 writers. Upon the knowledge that she didn’t write the original song, many collaborators have fiercely rejected the claim that she had no part in the creation of the song. They have claimed that her contributions, much like that of Justin Bieber’s, come in the addition of her own unique style of interpreting the song with her voice.

Ryan Tedder, for example, the songwriter for “Halo” and “XO” explained, “She does stuff on any given song that, when you go from the demo to the final version, takes it to another level that you never would have thought of as the writer…For instance, on ‘Halo,’ that bridge…is completely different to my original one. The whole melody, she wrote it spontaneously in the studio.”

This critique of Beyoncé has also often been retorted by many as sexist and racist. This is due to the many artists who share a similar profile to Beyoncé (also feature a similar quantity of collaborators on their albums, share a similar type of fame, also considered a singular genius) but are not criticised nearly so harshly for sharing the work.

This includes artist like Kanye West who cited over 100 collaborators on his 2016 album The Life of Pablo, as well as Rihanna, the Weeknd and Justin Bieber who all had over 30 writers (not including the copious amounts of producers cited) on their most recent albums.

In an article for the New Yorker, John Seabrook makes the point that when we watch a movie, the actors aren’t expected to have written the script, designed the set or the sound. Seabrook explains that music has a unique quality that differentiates it from music, that “a great song touches places in your heart that spoken words can’t reach.” The comparison also inspires an alternative interpretation, that collaboration in creating music as an artform should be seen as the norm, just like in the making of films.

Art is not created in a vacuum. No single individual can live and then create completely free of external influences. There is no method of measurement for how a piece od art was impacted by extrinsic elements, whether this impact is intentional or otherwise.

What I propose as a solution for the philosophical dilemma of artistry in music is two-fold, stemming from both the artist and the listener.

Artists, like Beyoncé who has been cited as misleading people as to who has written music, should use pronouns such as ‘we’ as opposed to ‘I’ when referring to the writing process for her music. The collaborative process in art should not be shunned, it should be appreciated and normalised. Many people working together can allow for a richer, more nuanced artistic expression of human experience.

Those who are listening and interpreting music should consider the piece of art as separate from the name of the individual that is representing it. We should move away from so strongly elevating a single person as a transcendent, divine being. We should recognise their art as a product not only of multiple people but as part of a larger musical and socio-cultural movement.

Developing these understanding allows for a greater appreciation of music genres that are inherently and historically built from collaboration, which spans across genres from hip-hop to electronic dance music.