It’s been dubbed “the scariest movie of all time,” but there’s nothing new about Hereditary‘s use of the “final girl” trope. Starring Toni Collete and directed by Ari Aster, Hereditary tells the story of a woman living in a paranormal nightmare after the passing of her sick mother. Sound familiar? If you’re a movie buff, of course it does. The horror genre has been making use of this popular archetype for decades. But why is cinema obsessed with these “final girls?” Do their popularity speak of a complex gender construction, or do they simply make for better entertainment?

Popular culture has been soaked with iconic final girls since the Nineteen-seventies and probably earlier. While unknown men, masked monsters, or grudge-filled ghosts do the offending, horror’s women are running, fighting and, well, just trying to stay alive. It’s a tough gig but someone has to do it, right? Even popular parody films like the Scary Movie franchise cleverly adapt this trope with the inclusion of a final girl in every one of their comedic exploits on horror, usually always played by Anna Faris.

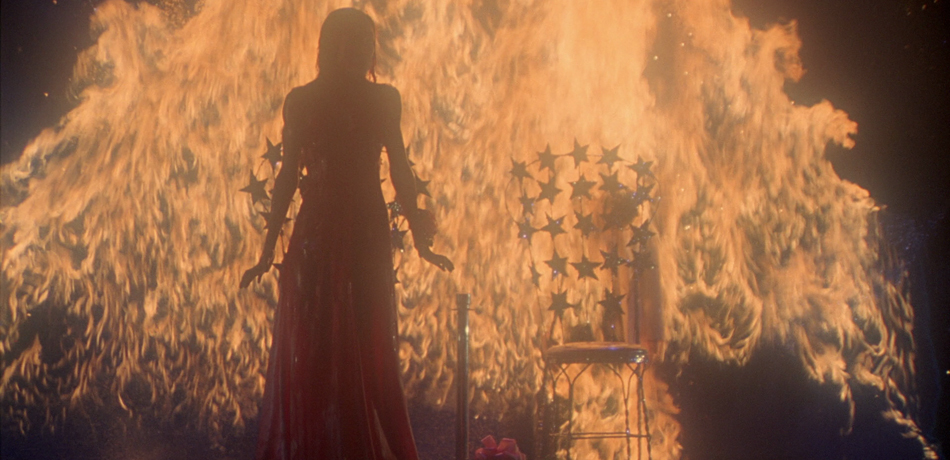

Maybe we could call Carrie (1976) the first It-girl of final girls. A troubled Catholic girl with a God-fearing mother, the story of Carrie’s wrath of her schoolmates at the high school prom has become legendary. Anyone who has watched the film, or even read the book, can pick up on the intentional gendering of a character – a demure girl who is brought up to fear her own sexuality and abide by authority from her cruel mother (another interesting perception of gender). Even her modest appearance and costuming is altered to that of a shy teenage girl, devoid of any personality.

The predicted formula follows Carrie from the very first frame right up until the credits roll, but there are two potential readings to be taken from this feminine depiction of a girl in trouble, which makes Carrie’s character altogether more conflicting. Cue the final scene of Carrie. Watching Carrie’s explosive telekinetic outburst is a magnetic scene filled with blinding light and the sound of screams as she stands drenched in pigs’ blood. Most women, including myself, could read this scene as a triumph for a bullied Carrie, she’s finally broken the chains of her repressor and unleashed her fury. Others could see it as chaotic and unruly female rage – a teenage girl controlled by her fickle emotions. I’ll give it to Carrie for tapping into a buried fire within her, a feeling most can relate to. However, the production value and effects outweigh the symbolism and yes, could just be made for a highly entertaining scene of horrific murder. In the case of Carrie, the final girl left in her high school, I’m both scared but strangely empowered by her unforgiving form of revenge.

From the high school halls to outer space, here’s another final girl and my all-time favourite on-screen lady. Ellen Ripley, played by Sigourney Weaver, from sci-fi franchise phenomenon Alien (1979) is a final girl like no other. Her confrontational edge and all-round badass demeanour don’t see her cruising with any chainsaw massacre-esque final girls. Instead of a pretty, well-to-do final girl whose boyfriend goes bad, Ripley’s role as a fearless space adventurer fighting one-on-one with a galactic space alien is refreshing and quite revolutionary for its time. She’s an icon in my eyes; a symbol of undeniable endurance and perseverance coupled with a fighter’s spirit and refusal to just float out into space.

Right to the third instalment of Alien, Ripley constantly challenges the gender politics embedded in the final girl. She represents a groundbreaking portrayal of a tougher femininity – a concept lost in most horror films. There’s a stark contrast between her unflinching strength compared to that of the softer females in gory blockbusters. Of course, a blockbuster of Alien-sized proportions couldn’t back away from the concept of maternal instincts kicking in at the sight of a child. For Ripley, it’s the surprise introduction of young Rebecca in Alien, an orphan who Ripley fiercely protects. Clearly, there was no escaping some traditional form of feminine values here, thankfully it doesn’t hinder her determination to terminate more aliens. Again.

Hollywood’s fascination with women making it to the end of whatever demonic or otherworldly force they’re up against seems to be working for viewers worldwide, I too am guilty of wanting to see them get to the end (without being scarred for life). Keep fighting, girls. I know we’ll be seeing more you of in many horror films to come.

So how will Toni Collette’s character Annie Graham fit the final girl mould? Stay tuned to find out.

Hereditary hits Sydney theatres June 7th.