Fashion Industry Broadcast and Style Planet TV is proud to present its new 10-part Film docuseries “Renegades”. As a teaser before the 10 films are released, we reveal the part of the story on Vivienne Westwood, who is one of the Renegades we are featuring in a new hour-long feature film, as a part of our full series.

Our Renegades refused to follow the laws of the ‘fashion rulebook’. The dreamers, the rebels, the auteurs, without whom popular culture would never have been quite as interesting. Even if you hold only the most casual interest in the world of fashion, it’s hard to deny the fascinating life stories of every one of our Renegades.

Featuring the lives and legends of;

- Alexander McQueen

- Yohji Yamamoto

- Rei Kawakubo

- Issey Miyake

- Kenzo Yakada

- Malcolm McClaren

- Vivienne Westwood

- Jeremy Scott

- Rick Owens

- Hedi Slimane

We present to you: VIVIENNE WESTWOOD

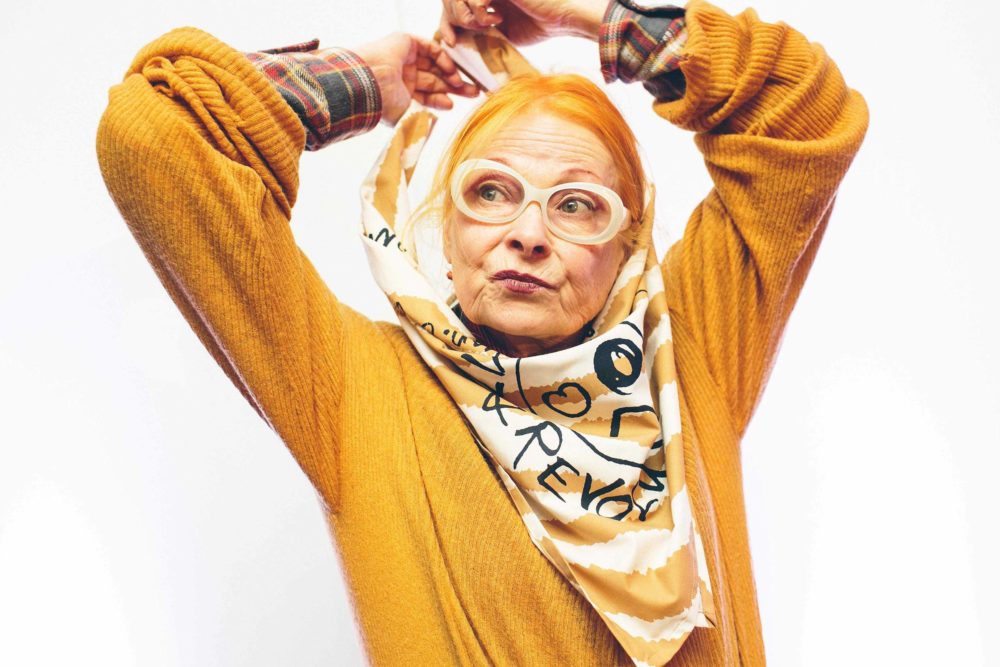

Punk. Dame. Designer. Rebel. Millionaire. Mother. Radical. All words one could use to describe Vivienne Westwood, a woman who is perhaps the most influential British designer the world has ever seen.

In an industry predominantly created to showcase beauty, Westwood uses her skills to advocate higher causes, through her passion for art, history and social justice. In doing so she redefined what being a designer could represent, inspiring a wave of others dedicated to using fashion as a means of sparking cultural change.

Westwood was born in 1941, in the village of Tintwistle, Derbyshire. Her parents, Gordon and Dora, had met two years previously at the onset of the Second World War. She was the eldest of three children, in a family far removed from the English elite: Gordon worked as a storekeeper in an aircraft factory while Dora helped make ends meet by working in a local cotton mill.

Nevertheless, Westwood was always close with her parents, who imbued her with a confidence and self-sufficiency rarely seen in a woman of her generation. She would often be found wandering the countryside of Derbyshire, climbing trees and jumping streams in a manner most parents would disapprove of for a young girl.

“I liked being me, and I happened to be a girl. I wanted to be a hero and saw no reason why a girl couldn’t be one.”

Her heroism developed through her schooling years. Despite her enjoyment at school – she was a proficient reader – Westwood saw herself as “a kind of champion” for the marginalised, standing up to authority figures at the behest of others who could not, or would not, stand up for themselves.

On numerous occasions in class she would take the blame for actions that were not her own, testing the boundaries of authority figures such as teachers and finding fulfilment in the “glamour of the self-righteous.”

Despite a love of education, her parents were wary of the abstract knowledge of books, preferring Westwood learn the more practical knowledge of trade craft. Gordon and Dora hailed from generations of grocers and shoemakers, and both were deftly skilled with their hands. Dora, in particular, was a gifted seamstress who insisted on sewing all of the clothes for her children.

Vivienne’s parents moved to Harrow, London in 1958, overseeing the running of a local post office. Westwood, 17 at the time, enrolled in the nearby Harrow School of Art to study as silver-smith; but after a single semester she opted to drop out of the school for good.

It was one of the few times in her life her infallible sense of confidence failed her. “I didn’t know how a working-class girl like me could possibly make a living in the art world.”

Westwood instead took a job at a factory while studying at a teacher-training college, eventually becoming a fully certified primary school teacher.

By 1963 her life was seemingly on a track towards the inconsequential. Vivienne had married Derek Westwood, a handsome mod who ran dance halls and aspired to become an airline pilot. Within the same year she gave birth to their first son, Ben.

Derek was a dedicated father and a supportive husband. But Vivienne was anxious in the role of matriarch: “I wasn’t happy. I wasn’t content looking after my child. I needed to know more of the world.”

Vivienne left Derek a few months after the birth of Ben and was back living with her parents above the latest in a series of post offices they now ran, continuing to work as a teacher and selling handmade jewelry on the side.

But in 1965 everything would change for Westwood. Her brother, whom was studying at a local art school, would often invite friends back to the post office. One in particular, a pale redhead by the name of Malcolm McLaren, was particularly drawn to Vivienne and offered to help craft her jewellery.

“I was very impressed by his designs,” Westwood recalled. “They were very mod.” McLaren persisted in his pursuit of Westwood, who eventually succumbed to his advances of the then 19-year-old McLaren.

A few weeks later, Westwood was pregnant for the second time. McLaren was a chaotic figure born into supreme family dysfunction: he held no interest in being a father and secured the money for Vivienne to have an abortion. But on the way to the clinic she had a change of heart, spending the money on a cashmere twinset instead.

Westwood’s second son, Joseph Corre, was born in March of 1967. His surname was dedicated to McLaren’s grandmother Rose Corre: the same woman who only months beforehand had paid for Westwood to have him aborted.

True to his word, McLaren was utterly disinterested in fatherhood. He showed up six days after the birth of Joe to visit Westwood; and in the ensuing months, continuously reminded her how unattached to his child he was.

Their relationship was acrimonious at the best of times. After separating from McLaren in 1968, Vivienne quit work to take care of her sons, living out of a caravan with no running water in a remote part of Wales.

Though Vivienne returned to him more than once, in recent years she has stated she never wanted to be with McLaren but found herself overwhelmed by his obsession for her, that manifested itself in emotionally and sometimes physically abusive behaviour.

But Westwood was herself obsessed, fascinated with his unique perspective on the arts and disregarding authority: two longstanding passions that had fallen by the wayside.

“I latched onto Malcolm as somebody who opened doors for me. I mean he seemed to know everything I needed at the time.”

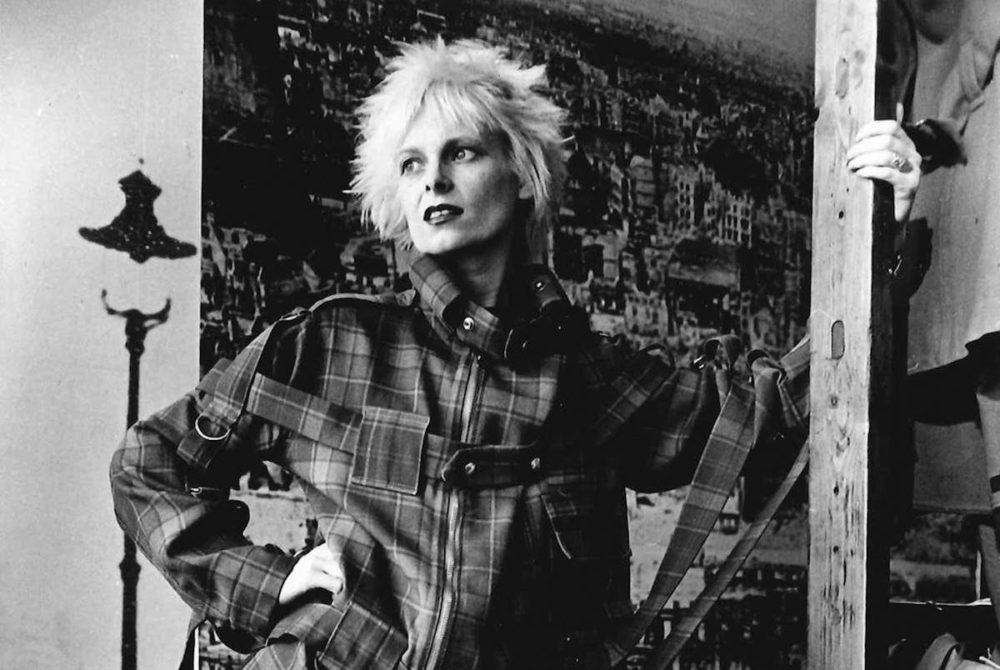

McLaren was instrumental in changing her look from “dolly bird into a chic, confident woman.” He made her wear outlandish outfits – such as a schoolgirl uniform with red latex tights – in an effort to erode her confidence by dressing her like a prostitute.

Her new look only emboldened Vivienne’s independent steak and her renewed passion for design. Together the tumultuous couple opened a boutique in 1971 named Let It Rock.

After flirting with several styles – rockabilly, mod, and greaser – McLaren stumbled across the punk movement during a trip to the New York underground and decided to import it to the United Kingdom.

McLaren and Westwood changed their boutique’s name to SEX and embraced the punk ethos and its anti-authoritarian stance.

While McLaren recruited a band to model their attire, most of the fashion we now associate with punk – from spiked dog collars to clothes strung together with safety pins – were designed and constructed by Westwood in the couple’s South London apartment.

“I particularly loved my SEX look: my rubber stockings and the T-shirt with pornographic images and my stilettos and spiky hair… I stopped the traffic in my rubber negligée.”

McLaren was a superlative promoter who used the success of his band The Sex Pistols to take their boutique to new heights of success, while Westwood pushed the boundaries of what punk could represent, incorporating politically-taboo messages with scandalous bondage themes as a means of shocking the establishment and disrupting the status quo.

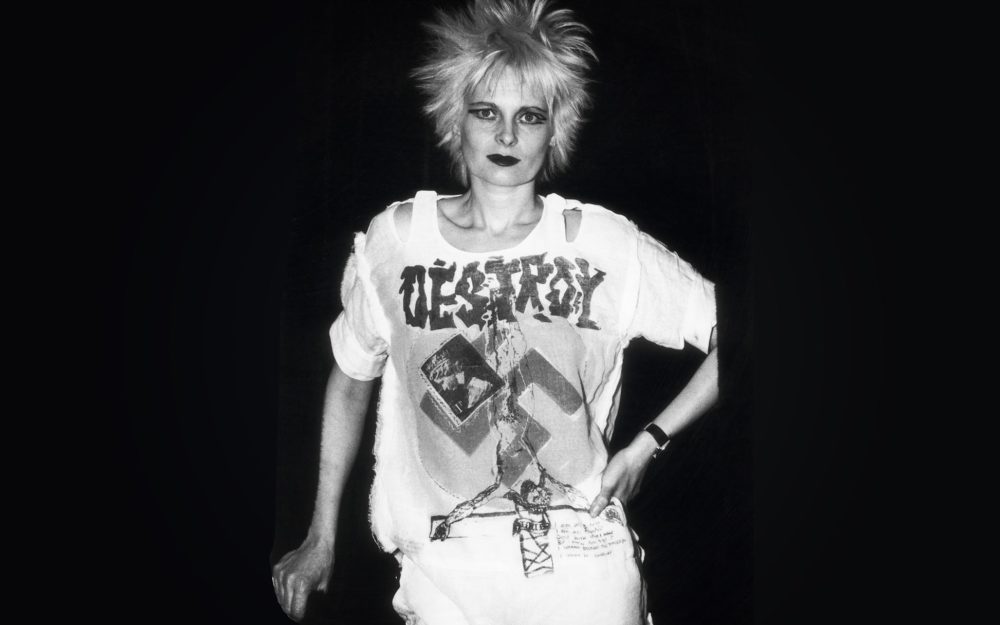

One such instance is the infamous “DESTROY” shirt, emblazoned with an enormous swastika across the front. Even into her later age Westwood has no regret about her design choices: “we were just saying to the older generation, ‘We don’t accept your values or your taboos, and you’re all fascists.’”

By 1977 the Punk influence had infected all of Britain. The Sex Pistols were the biggest band in the country and off the back of their success the boutique, now labeled Seditionaries, had become the epicenter of the movement.

Thousands of disenfranchised youths across the country were wearing designs either created or inspired by Westwood. But once more in her life, Westwood lacked contentment.

Her dedication to the punk movement had come at a cost. Westwood has acknowledged she was an unfit mother at the time, stating “I neglected my children because I had to do certain things, which meant that I couldn’t be there for them – in order to do ‘fashion’, because, at the time, I thought fashion was a kind of crusade.”

To make matters worse, McLaren refused to share the success of bringing punk to the mainstream, referring to Vivienne only as his “seamstress” and denying her the design credit she deserved.

But her true dissatisfaction with punk came in the ideology. For McLaren, punk was a sustained disruption of order: chaos for the pure sake of chaos. But for Westwood, punk was social change through radical action, a means to “confront the rotten status quo through the way I dressed and dressed others.”

“I was messianic about punk, seeing if one could put a spoke in the system in some way.”

Under the guidance of McLaren, the punk movement had become a circus of hedonism and aimless rebellion, not the revolutionary battle cry Westwood was hoping for. “When I turned round, on the barricades, there was no one there. That was how it felt. They were just still pogoing. So, I lost interest.”

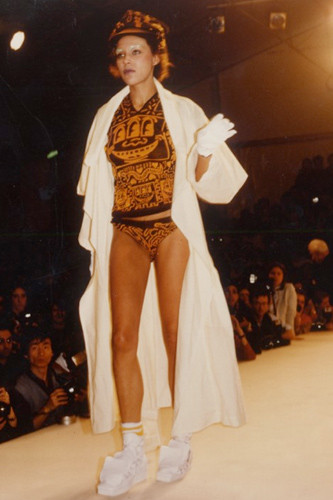

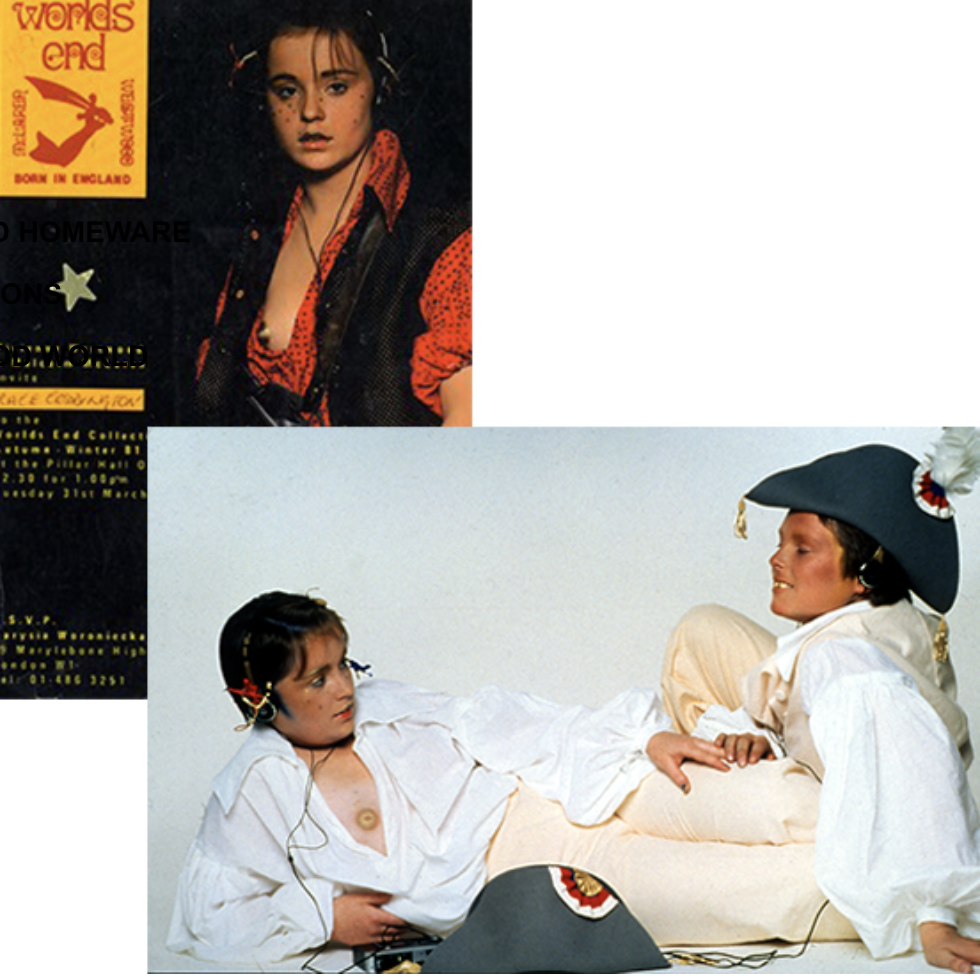

By the early 1980s Vivienne had tired of the punk ethos and yearned to push her sense of design to new places. She and McLaren remodeled the boutique one final time, naming it World’s End, and in 1981 the pair launched their first catwalk collection, Pirate.

The collection consisted of clothes influenced by the golden age of buccaneers and highwaymen ans was an instant hit with the fashion world. Westwood was no longer rattling the establishment from the outside: she was actively working within mainstream culture to influence change.

McLaren and Westwood followed Pirates with a number of collections she later grouped under the banner “new romantic.”

Each collection was profoundly different from the next as Westwood flexed her creative muscle: Savages (spring 1981) was influenced by Native American patterning with a twist of Foreign Legion; Nostalgia of Mud (autumn 1982) embraced enormous tattered shirts and sheepskin jackets saturated in muddy colours; Punkature (spring 1983) drew inspiration from Ridley Scott’s dystopian sci-fi classic Blade Runner whilst, Witches (autumn 1983) conjured the “magical, esoteric sign language” of the New York graffiti artist, Keith Haring.

Witches proved to be the final collaboration between McLaren and Westwood; after over ten years, the couple dissolved their tormented relationship.

Free from her previous constraints, Westwood began to find her true voice as a designer. She began to draw a great deal of inspiration from the annals of history, sourcing ideas from the literary and cultural expertise of Gary Ness, a former painter with whom Westwood had developed a close bond.

Westwood saw a fellow ideological iconoclast in Ness: someone she could rail against the barricades with; who could help her say exactly what she wanted to through fashion.

By shirking the futurist conventions of fashion and turning to the past for inspiration, Westwood found greater success in her future than she ever could have imagined.

One of Westwood’s first major accomplishments as a solo designer was the “mini-crini” of 1985. Combining the tutu with an abbreviated form of the Victorian crinoline, it was a simultaneous rejection of the masculine shoulder pads popular at the time, and a cultural homage to the classic Russian ballet Pretushka.

Following the mini-crini, a random encounter with a young woman in London proved the inspiration for one of Westwood’s most iconic collections: the Harris Tweed of A/W 1987.

“My whole idea for this collection was stolen from a little girl I saw on the tube one day. She couldn’t have been more than 14. She had a little plaited bun, a Harris Tweed jacket and a bag with a pair of ballet shoes in it. She looked so cool and composed standing there.”

The collection, partially inspired by the British Royal Family and notable for its use of 18th century corsets, was a runaway success and cemented her position as one of the most influential designers in the world.

Westwood continued to find sartorial inspiration by delving into the catacombs of cultural history: Pagan I, for example, was an eccentric mix of traditionally British fabrics and pagan design elements, with patterns procured from the pornographic images of Ancient Greece.

Time Machine, 1988-89, was of similar eclectic design. Named after the eponymous H.G. Wells novel, the collection used tweed to construct suits modeled after medieval armour.

And Cut and Slash of 1991 took its layered textile design from a 16th century French tradition, in which they would cut and prick fabric in such a way that it would last for hundreds of years.

Vivienne Westwood was one of the most established names in fashion by the mid-90s. Her fascination with the cultural histories of the English and French saw her create some of her most inspired designs at the time.

Some of the designs were almost unwearable by conventional standards. The 1997 collection Les Femmes ne Connaissent pas toute leur Coquetterie (“women do not understand the full extent of their coquettishness”), for instance, incorporated the use of body extensions such as padded busts and hips, along with bustles created by metal cages to create an exceptionally exaggerated hourglass silhouette.

Westwood’s designs often ran contrary to the fashions of the time. Her Dressing Up was an example of exactly that – an elaborate display at a time when economic downturn saw the majority of designers moving in the opposite direction.

And as fashion increasingly became infused with minimalist aspects, Westwood remained as intricate as ever. The 2000s saw her move away from historical influence and into the textures of fabric itself, treating it as a living mass.

It was Gary Ness, her cultural guru, who first saw the true potential of Vivienne Westwood. She was not a revolutionary but a counter-revolutionary: willing to reject the bland populism of modern fashion in favour of a much higher ideal – a return to the realm of high art.

Paradoxically, in her rejection of conventional trends Westwood became a trendsetter herself, influencing dozens of designers who have taken inspiration from her decades of work. Meadham Kirchhoff acknowledged their debt to Westwood in their SS15 collection, declaring they were “forever indebted” to her genius, while notable contemporary designers such as Raf Simons have spoken of their love for her unconventional and detailed designs.

A major factor to her continued success comes in the form of husband Andreas Kronthaler, her loyal design partner and perhaps her biggest advocate. After a decade of avoiding men following the difficulties she faced with McLaren, Vivienne met future husband Andreas while teaching at the Vienna Academy of Applied Arts.

Vivienne, then 48, was impressed with Andreas’ designs and invited the 23-year-old to London to work with her. He shared her vision of fashion-as-art and held a more supportive, collaborative disposition than McLaren could have ever imagined. They quickly became an item and married in 1993.

Together they oversaw the stratospheric rise of Vivienne Westwood Ltd, which now boasts 63 outlets worldwide and has instilled Vivienne with an estimated net worth of $185 million.

Yet over the past decade Vivienne has become less involved with the day-to-day planning of her fashion empire, preferring to use her fame and wealth to advocate numerous social causes, leaving Kronthaler with greater creative input over her company.

Vivienne has publicly supported numerous causes, often using her fashion empire as a means of drawing attention to issues. The designer set a 2011 campaign against the backdrop of a Nairobi slum to advocate her partnership with the Ethical Fashion Africa Programme.

In 2013 she drew attention to the cause of Julian Assange by using his name and image in her designs.

But by far, her greatest cause is climate change. The long time Labour Party supporter who swapped to the Conservative Party in 2007 is now the largest donator to the Green Party of England and Wales because, in her own words, “I am traumatised by the problem of climate change.”

In 2005 she started Active Resistance, a project designed to stimulate engagement in humanitarian and environmental issues. Many of her recent collections have centered on the concepts evoked in Active Resistance, including 50+, the 2009 collection that cultured inspiration from the predicted temperature of the Earth if climate change is left unchallenged.

Nearly a decade later, Visionaire Magazine, in celebration of its’ 68th issue, commissioned 10 artists and activists to design a digital protest poster for its 2018 readers. The idea was to address the current social issues afflicting the world and to elevate the simple protest poster through the context of art, powerful messages from powerful people. For Visionaire selecting Westwood was a no-brainer, the Brit designer for whom fusing art and activism was at the heart of her long career. Rather than exploring a new issue, Westwood used the platform to drive home her longstanding campaign on the effects of climate change from the Active Resistance era. Westwood’s graphic poster depicts a bleak map of the world should the earths temperature rise by just 5 degrees, with all the uninhabitable parts marked in red. Outside of this moment, Vivienne Westwood continues her activism on a more permanent scale offering a line of protest t-shirts alongside the main brand. Her latest take-down is aimed at a pro-fracking sponsor of the 2021 America’s Cup, Westwood aims to highlight the hypocrisy and impact that such an alliance would have on World Sailing and the safeguard against damaging environmental practice.

Vivienne has used her celebrity in a number of different ways to draw attention to her causes, including shaving her hair off to draw attention to the issue of climate change and appearing in a PETA ad campaign to promote World Water Day in order to highlight the water consumption involved in the meat industry.

Her crusade against climate change has found her squarely at odds with the industry that generated her fame. She is a staunch opponent of the wastefulness in fast fashion and encourages people to “not buy clothes,” declaring that people should commit to a select number of pieces rather than an expansive, interchangeable wardrobe.

There is an air of contradiction surrounding Westwood in this sense. She decries the fashion industry as she profits from it, and bemoans the influence of advertising while creating celebrated campaigns with some of the highest profile photographers in the world.

Westwood rails against the establishment while at the same time instilling herself as an essential component, socialising with billionaires like Richard Branson and appearing on talk shows in ludicrously expensive silk dresses while complaining about the wasteful state of the bourgeois.

And yet it doesn’t feel hypocritical. Westwood believes everything she says with passion and fervor; she manages to hold contradictory sentiments and still deliver them in the most honest, confident manner she knows how.

“What I’m doing now, it still is punk — it’s still about shouting about injustice and making people think, even if it’s uncomfortable. I’ll always be a punk in that sense.”

Perhaps that is the key to Westwood’s success. Long after the chaos-inducing punks have burned out to their ineffectual ends, Vivienne Westwood is still standing strong. She made a conscious decision to move from the sneering outcasts to a member of the social elite, using her social stature to challenge the status quo and find people willing to rail against the barricades with her.

She has moved from putting a spoke in the system to being a spoke in the system, earning the mantle of Britain’s most inspirational designer along the way.

And for those who consider Westwood too far removed from her early days of punk, consider this: when the woman who dressed the band famous for God Save the Queen received her dame hood in 2006, she did so wearing a beautifully tailored dress – and no knickers. A true symbol of her anarchic character.

From the Pirate Collection of 1981 alongside McLaren right up to the Spring Summer 19 Show presented by Andreas Kronthaler, the brand continues to deliver all the theatrical and absurdist high notes we have come to expect of a Vivienne Westwood runway with antics that stem from it’s activist roots. Kronthaler’s vision transformed a Parisian garage into an installation of creative chaos for the latest unveiling. A cloud-like structure sat at its centre like the eye of the storm, whilst men on ladders painted the air and body builders whizzed nonsensically by. Critics are quick to point out the distraction it poses, yet despite all the chaos “those distractions” continue to cut through and have a positive financial impact on the brand, with Vivienne Westwood remaining one of the houses to ride out the economic storm with the bulk of it’s sales concentrated in the UK.

This Westwood affect is certainly not lost on Riccardo Tisci. The current creative director for Burberry courted a Westwood collaboration, wanting to inject “her unique representation of British Style” into re-imagined works from the Burberry archive. The collection will feature Burberry’s signature check print together with the punk sensibilities of Westwood and will fall under a new logo created for the limited edition line, that merges the signature branding of Burberry and Westwood. In line with the philanthropy of the houses, the profits from the unique capsule collection will go towards the Cool Earth organisations fight against deforestation.

A dedicated patron of Cool Earth, Westwood recently attended the new location launch of Cool Earth affiliate, restaurant Sushi Samba. Aside from furthering her causes, the 77 year old’s continued presence on the British social scene helps to keep her connected with a younger audience.

Not that she needs to in order to stay relevant, the Westwood brand continues to speak to the British people who are disenfranchised by the current age of the global financial crisis, climate change, terrorism and political upheaval. Her clothes and brand by association, offer the youth of today the same outlet for provocation and rebellion as it gave to the punk rebellion of the late 60s and 70s. For this reason, Westwood caught the attention of documentary film maker Lorna Tucker. Her recent film Westwood: Punk, Icon and Activist aired at the DocLisboa annual film festival and was an intimate portrait of the woman and designer behind the iconic brand. Tucker states “punk is once again the global style trend of discontent. People worldwide are unhappy – about everything from Brexit to right-wing politics, and punk is once again turning into the visual language of their grievances”.

The genius of Vivienne Westwood is in her ability to identify that undertone and present it on a unified platform. Even to the point of creating her own army of freedom fighters. For her Autumn Winter 18 campaign, Vivienne pulled together a collective of conceptual artists and activists to continue her work. Instead of a runway, a short film of street-cast models talk empowerment and rebellion. A sentiment of war permeated the collection, a sort of “call to arms” for those wishing to use clothes as a tool for change and free expression. Shot in a London between the studio and the neighbourhood of Parsons Green, Vivienne garbed her muses in deconstructed tailoring, camouflage and regimental details, set amongst the prayer flags she designed not just as a message or artistic point, but as a strategy to save the world. In the latter stages of her life, blunt tactics are the way forward for Vivienne’s vision. “Don’t Get Killed” is just the start of her awakening tactics to a life where climate change and mass extinction are no longer on the cards.

Beyond the film, Six of “Vivienne’s Creatives” from the Autumn Winter army have contributed to some of the unique perspectives on offer through the brands main site, sharing their artistic projects and social agendas for the next generation. The UK has a history steeped in revolution, change that was ignited by trailblazers like Westwood herself, whom whilst still actively charging against injustice is ensuring that her legacy that will extend beyond her own years.

It is this dedication to a cause, her natural authenticity, that has made Westwood the voice for not just any one generation nor institution for that matter. Whether designing for the Royals or the “pirate commoners”, Vivienne makes ideas accessible by transforming the fashion world into a discourse for those very ideas, symbols that just happen to be great clothes. She has fulfilled her own prophecy as a young girl becoming the hero – nay – Queen of the fashion world, that British renegade who defined the rebellion behind the punk movement and gave us originality in spades – the one and only, Dame – Vivienne – Westwood.

Check back every Friday for the latest teaser for FIB and Style Planet TV’s newest docuseries, Renegades.

Written by: Charlie O’Brien

Edited by: Jess Bregenhoj