Fashion Industry Broadcast and Style Planet TV is proud to present its new 11-part, hour long film docuseries “Renegades”. As a teaser before the 11 films are released, we are revealing a post on THE BROADCAST each week for the next 11 weeks. This week the story is on Malcolm McLaren. He was Vivienne Westwood’s partner for a time, and whilst not a fashion designer as such like our other 10 Renegades he was in every way an icon in design, music and left a lasting imprint on the world of culture as the Godfather of punk.

Our Renegades refused to follow the laws of the “fashion rule book”. The dreamers, the rebels, the auteurs, without whom popular culture would never have been quite as interesting. Even if you hold only the most casual interest in the world of fashion, it’s hard to deny the fascinating life stories of every one of our Renegades.

Featuring the lives and legends of:

- Vivienne Westwood

- Malcolm McLaren

- Hedi Slimane

- Rei Kawakubo

- Issey Miyake

- Kenzo Takada

- Yohji Yamamoto

- Alexander McQueen

- Jeremy Scott

- Rick Owens

- John Galliano

We present to you: MALCOLM MCLAREN

Malcolm McLaren was not, by any measurable standard, a good man. He left a trail of wreckage everywhere he went, birth until death, channelling his sense of dysfunction into one of the most potent subcultures in modern history. The godfather of punk didn’t just embrace chaos – he made it fashionable.

The seeds of the McLaren dissent were sewn early. He and his parents lived in North London with grandmother Rose, an eclectic woman from a wealthy family of Portuguese Sephardic Jews.

McLaren’s mother had wed for money and found herself trapped in a loveless marriage, with a child she held little affection for.

It was, ironically, the mirror life of her mother. Rose had been forced into an unhappy marriage, rearing a child “she didn’t really like,” in the words of her grandson.

The lineage of irony was never lost on McLaren: “to be honest, I don’t blame her. I never liked my mother either.”

McLaren’s mother drifted in and out of his youth, more interested in chasing men – it was rumoured she was a prostitute – than she was in caring for her child.

Childrearing duties were left in the hands of Rose, who had already paid her son-in-law a handsome fee to abandon his wife and child.

Not that this seemed to bother McLaren. He idolised his grandmother and her fractured sense of morality: an ethos underpinned with a singular message that would eventually form the basis of punk rock: “to be bad is good.”

“My grandmother taught me, from a very early age, to disregard anybody with any air of authority.”

School became the first proving ground of this anarchistic attitude, spitting in the face of authority – yet secure in the knowledge that his grandmother would protect him when true consequence arose.

His rebellion of authority never seemed to extend to Rose however, who held an almost cult-like influence on McLaren: forbidden to associate with girls and sharing a bed with his grandmother until he was 14, McLaren was a rebel only under the strangest, and strictest, of supervision.

By the time McLaren entered art school, chaos was the dominant force in his life. He was ejected from every school he attended – one went as far as to try and have him committed into a mental institution.

And yet along with his grandmother, McLaren saw his time in art school as a formative experience in his contribution to punk. It was here he became obsessed with the French Situationists, a cultural movement promoting absurd and provocative actions as a means of social change.

“They were all geared towards thinking that it was better to be a noble failure than a vulgar success,” McLaren said of the Situationists. “It meant you were not afraid to break the rules. You wanted an adventure not a career. We saw ourselves as romantics in the tradition of Byron, Keats and Blake.”

Romantic. It’s not a word one would traditionally use to describe McLaren – especially considering his long and toxic relationship with fashion designer Vivienne Westwood.

The circumstances of their relationship differ depending on the source you choose to believe: McLaren or Westwood. McLaren met Westwood through her brother, who was studying at art school with McLaren at the time.

Westwood, six years older than McLaren, claims he took an interest in her jewellery-making skills and relentlessly pursued the 25-year-old until she eventually conceded to have sex with him out of pity.

By his own admission McLaren found Westwood supremely annoying: “she held culture on a pedestal while I was always trying to knock it down.”

And yet there was a clear chemistry between the two. Westwood had been trying to escape a mundane existence as a primary school teacher at the time and was fascinated with the radical ideals that McLaren would espouse.

As for McLaren, “testosterone meant I couldn’t help but be attracted to her body. I found myself in bed with her one night and lost my virginity to her and suddenly she handed me the bill.”

The bill, as McLaren so charmingly put it, was pregnancy. McLaren was completely unwilling to raise a child and once again turned to his grandmother for help abandoning consequence.

Rose provided the money necessary for Westwood to have an abortion; but on the way to the appointment she had a change of heart, electing to spend it on a cashmere twinset instead.

McLaren “admired” her lack of cooperation but refused to be drawn into the responsibilities of fatherhood. “I was lost in that terrain. I’d been brought up to destroy families.”

But for the first few years, McLaren and Westwood attempted to raise a child in a conventional setting. It didn’t last: by 1971 McLaren had run out of art schools to attend and sank into depression.

To cheer himself up he began construction on a blue lamé suit and had Westwood assist him. It was then he realised the mother of his child was a “gifted seamstress.”

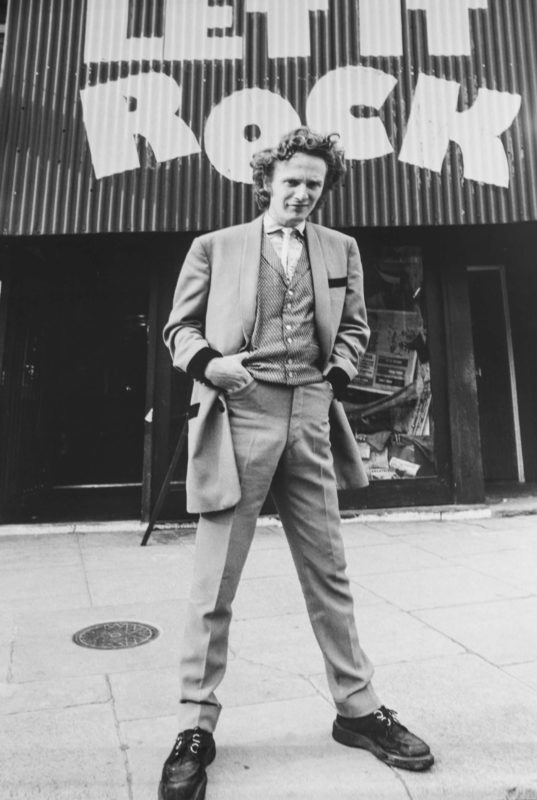

Leaving behind school for good, McLaren and Westwood opened a boutique along the now-famous King’s Road in Chelsea.

The boutique would undergo several transformations under the watchful eye of McLaren, but originally it was named Let It Rock, selling the rockabilly aesthetic of drape jackets, drainpipe trousers and brothel creeper shoes – a style popularised by the Teddy Boy subculture at the time.

By 1973 the store had been renamed – Too Fast To Live Too Young to Die – and shifted from rockabilly to the greaser fashions popularised in the 1950s.

McLaren was proving himself a shrewd promoter: each directional change drove the boutique to greater heights of success. But it wasn’t until 1974 that McLaren injected his personal mantra of dysfunction into the store and cemented his legacy as the man who brought punk to the masses.

The origins of the punk rock movement began in New York. McLaren and Westwood had been making periodic trips there since the early 1970s, exhibiting their clothes and strengthening their connection to the New York underground.

McLaren in particular had become fascinated with the anarchistic principles and radical fashion of the protopunk movement, forming relationships with trailblazing bands like the New York Dolls and Richard Hell of Television.

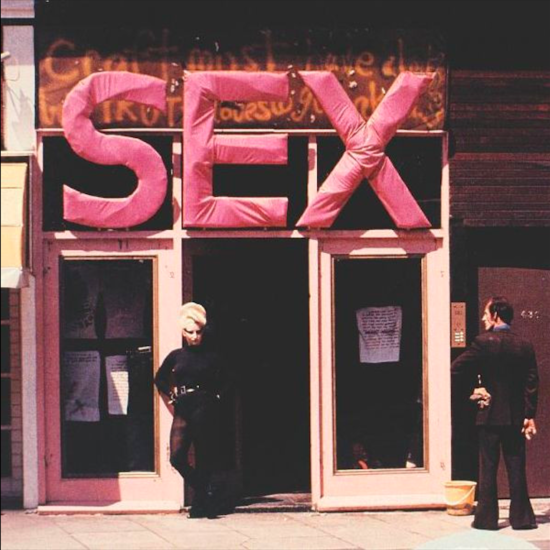

In the spring of 1974 he brought punk rock back to the UK, rebranding the boutique SEX and stocking the store with the bondage gear and socially provocative garments that would eventually become synonymous with punk culture.

Shortly after the inception of SEX, McLaren returned to the United States. It was there he met with New York Dolls guitarist Sylvain and agreed to become their personal manager.

Together they conspired on a new direction for the band, one that adopted the shock tactics of Communism: outfits inspired by the Maoist Red Guard and a host of socialist propaganda littering the stage.

Like so much of what McLaren did, the new look was designed to spark outrage. Instead, it simply caused confusion. The directional change proved the final nail in the coffin for the outfit and they disbanded not long after.

Undeterred by his failure at the helm of the Dolls, McLaren returned home with the goal of starting a new band: one he could use as “mannequins” to sell the fashion of punk.

He already had the perfect candidates. Musician Steve Jones had approached McLaren prior to his time with the Dolls about managing his band, The Strand – even convincing McLaren to pay for their rehearsal space.

Upon his return to the UK, McLaren set about moulding the band in his own personal image. Musical talent was not a prerequisite for inclusion; only those with the appropriate image needed apply.

As McLaren reiterated often throughout his life, “the fashion was much more important than the music. Punk was the sound of that fashion.”

John Lydon was a prime example of this mentality. McLaren had stumbled across Lydon in the street, sporting green hair and a tattered Pink Floyd t- shirt with the words “I HATE” handwritten across the top.

His vocal audition was so bad it drew laughter from the other members of the band but to McLaren, it was perfect: Lydon was angry, offensive and utterly malleable.

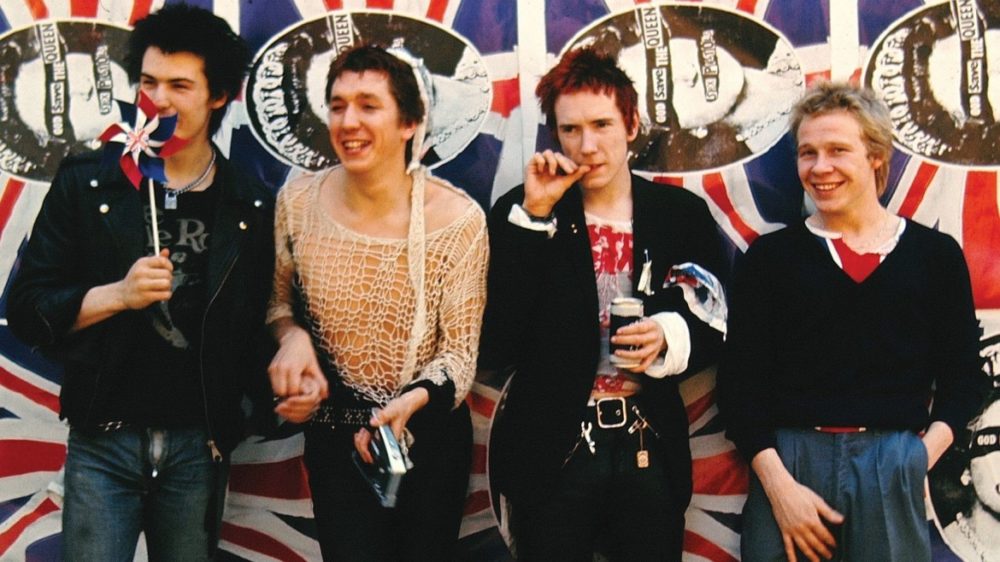

Lydon was rebranded Johnny Rotten and – along with the other band members – draped head to toe in punk garments conceptualised by McLaren and designed by Westwood. With a name change to reflect the name of the boutique, the Sex Pistols were born.

McLaren always asserted he was in the business of mismanagement, but under his guidance the Sex Pistols became the biggest and perhaps most influential punk band in the world – all in the space of three years.

The Sex Pistols were predicated on dysfunction – just like their manager. Chaos fuelled their quick rise to infamy even as it set fire to the foundations of the band. Behind it all was McLaren, orchestrating events that promoted the label of punk to the world, regardless of personal cost.

Within a year of forming, the band had their first record contract after generating a devoted following in the punk clubs of London.

But after a disastrous television appearance – in which a drunk Rotten verbally abused the host – sustained public and political pressure saw their contract revoked.

Bad for the band, good for McLaren; following their television appearance the Sex Pistols made the front page of every major newspaper.

Not only did it promote the culture of punk to the country; it was free advertising for the McLaren and Westwood boutique, now named Seditionaries and expanding on what punk culture could represent.

It wasn’t uncommon to find swastikas or communist badges pinned across tattered and stained punk garments. Westwood intended many of these to be delivered as political messages, but the nuance of protest was lost on most punks, who felt that causing outrage was satisfaction enough.

It was style over substance on many levels, and McLaren supported this vision of punk. In fact, when bassist Glen Matlock was fired for not fitting the image of the band McLaren opted for perhaps the single greatest instance of style over substance in rock and roll history: the hiring of Sid Vicious, a stalwart of the punk rock scene and a man with almost no musical proficiency.

“When Sid joined, he couldn’t play guitar, but his craziness fit into the structure of the band,” McLaren once recalled.

Crazy was an understatement. Vicious had been involved in a number of violent assaults – the worst of which had left an innocent girl blinded in one eye – and at 19 had already developed a substance abuse problem.

“After that, it was nothing to do with music anymore,” recalled Marco Pirroni, who played with Vicious in seminal punk band Siouxsie and the Banshees. “It would just be for the sensationalism and scandal of it all. Then it became the Malcolm McLaren story.”

McLaren secured a second record signing, but the deal fell through after the band stormed the office, destroying property and verbally abusing employees.

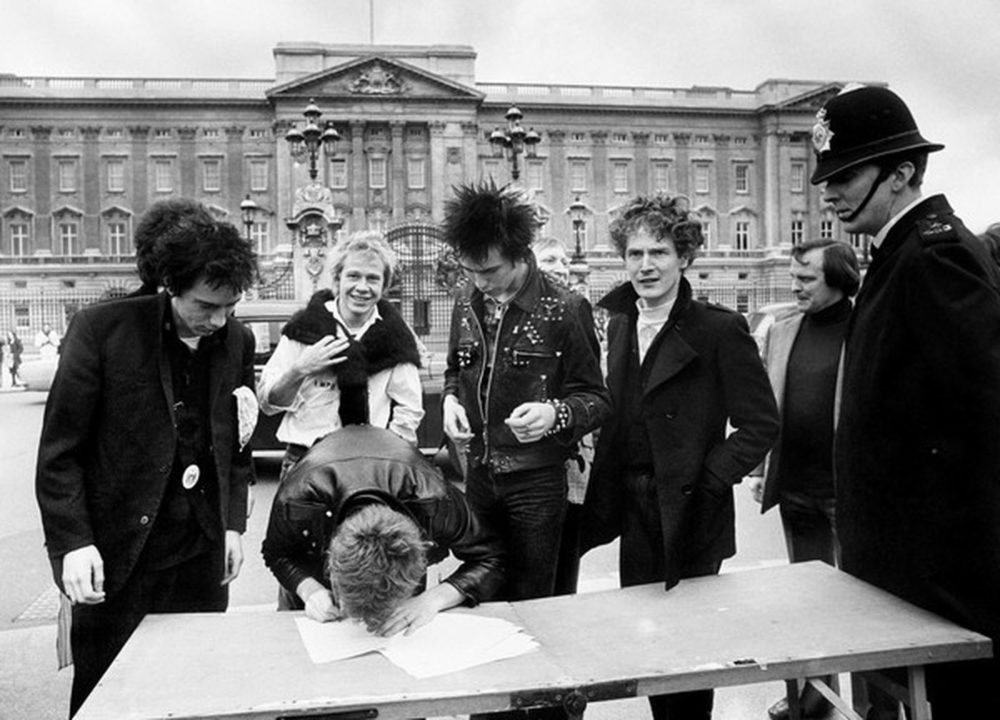

It was then a young Richard Branson signed them to his up-and-coming record label Virgin. To celebrate, McLaren orchestrated a boat trip down the Thames to coincide with the Silver Jubilee, playing their hit song God Save the Queen outside the houses of parliament. Police subsequently raided the boat and arrested McLaren, Westwood and a host of others for disturbing the peace.

It was a spectacular piece of anarchy-by-design that saw McLaren precisely where he wanted to be: in the spotlight. By this time the wider public were beginning to acknowledge that McLaren was the true force of the Sex Pistols.

When a reporter observed to Steve Jones that many people considered the band the brainchild of McLaren, Jones replied that McLaren was their manager and nothing else: “He’s got nothing to do with the music or image.”

It was an obvious fiction. Not only had their style been sculpted by the boutique of McLaren and Westwood, but Westwood had been filtering French Situationist philosophy through the lyrics of Lydon since their first single, Anarchy in the UK.

The band released their first and only album, Never Mind the Bollocks, in November of 1977. Despite a number of chain stores refusing to stock the album, it debuted at number one.

The cultural proliferation of punk had reached a zenith, and the mainstream was fighting back. Punk-related violence had skyrocketed in London; a number of people close to the band – including Johnny Rotten – had been viciously assaulted by conservative groups who viewed punk rock as a blight on society.

In front of Seditionaries punks went to war with rockabilly culture, assaulting the Teddy Boys that McLaren and Westwood catered to only a few short years ago.

The chaos of punk had grown beyond control, and it was no different inside the Sex Pistols. Vicious had become hopelessly addicted to heroin and splintered allegiances in the band. Rotten had grown increasingly sullen, incensed by continued accusations both he and the Sex Pistols were little more than marketing tactics designed by McLaren.

As his band stood on the precipice of collapse, McLaren used them for a final, sensational act of publicity; he organised a tour of America’s Deep South, confident their conservative values would clash with the anarchism of his band.

The results were beyond imagination. Vicious, completely unhinged on heroin, lived up to his namesake; assaulting several men and women on the first leg of the tour, attacking his own bodyguard and spitting blood on a woman who stormed the stage to punch him in the face.

Rotten had become disgusted with the actions of Vicious and the farce the band had devolved into, placing the blame of their fallout squarely on McLaren:

“[Malcolm] would not discuss anything with me. But then he would turn around and tell Paul and Steve that the tension was all my fault because I wouldn’t agree to anything.”

The band split in January of 1978. McLaren retained the rights to Never Mind the Bollocks, starting an incredibly public spat between Rotten and his former manager that resulted in the band suing for rights to their music, along with a million dollars in damages.

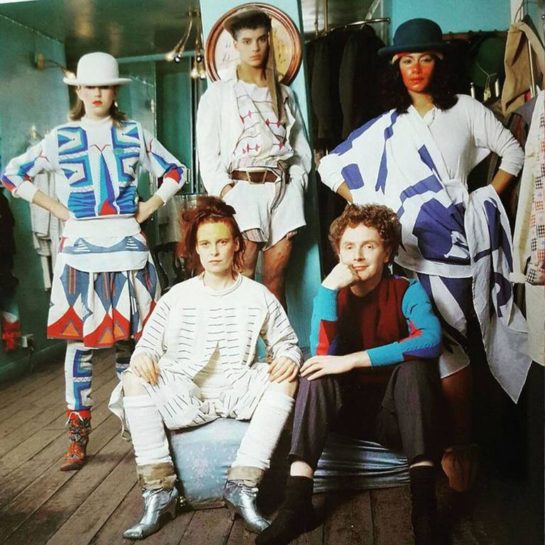

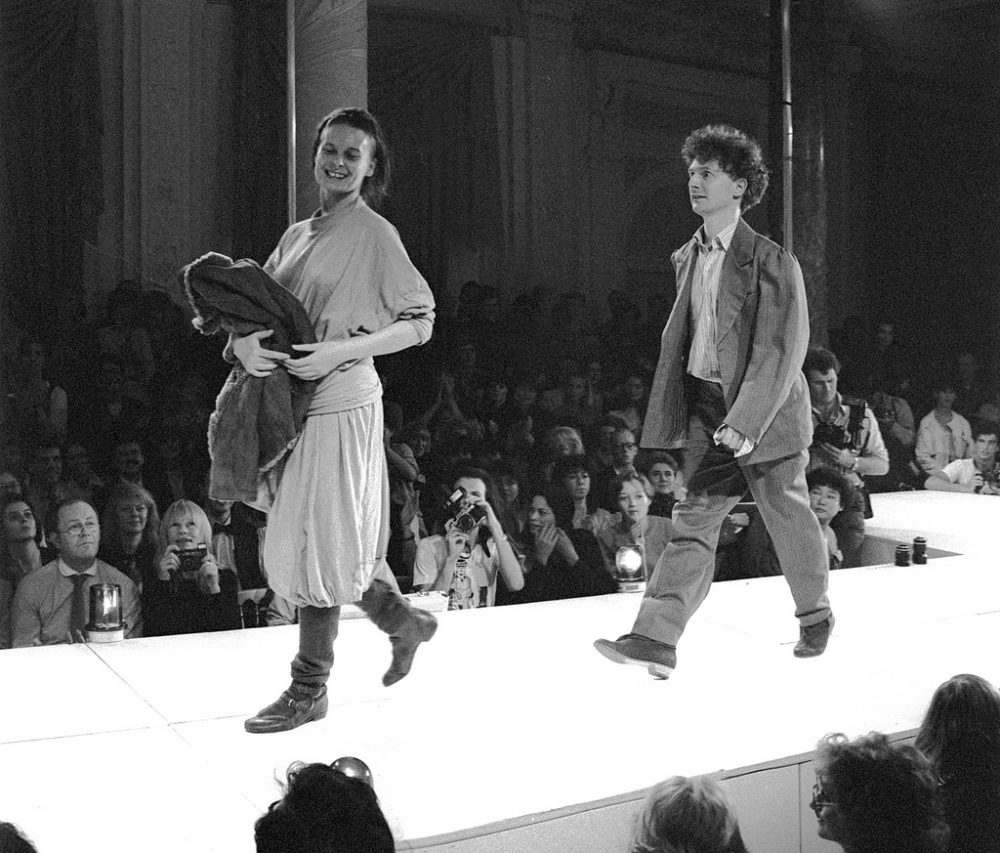

McLaren continued to work with Westwood following the dissolution of the Sex Pistols, changing the name of the boutique one final time – to World’s End – and collaborating on their first fashion collection, Pirates, in 1981.

Despite her monumental role as designer of punk fashion, McLaren only ever saw Westwood as his seamstress. But as she embraced her career as a professional designer it became increasingly clear where the talent for fashion lay in their relationship.

Together they created a number of collections under the McLaren and Westwood label, including Savages (1982), Punkature (1982) and Witches (1983).

In early 1984 their relationship dissolved and Westwood, having established herself as a prized designer, struck out on her own to open her own fashion label.

Decades after their relationship ended, Westwood spoke of the emotional and physical abuse she endured during their time together:

“He behaved incredibly cruelly. Professionally, personally, in every way… He had this thing where he couldn’t leave the flat until he made me cry. He wanted to feel bad or something – he was trying to draw blood.”

It’s a sentiment echoed by their son Joe Corre, with whom McLaren held a bitter and tumultuous relationship with, well into adulthood. Corre described McLaren as a “horrible bully,” and said the relationship between his parents was a “textbook case of a dysfunctional, toxic thing.”

And yet, McLaren claimed in his final years the only woman he ever truly loved – apart from his grandmother – was Westwood.

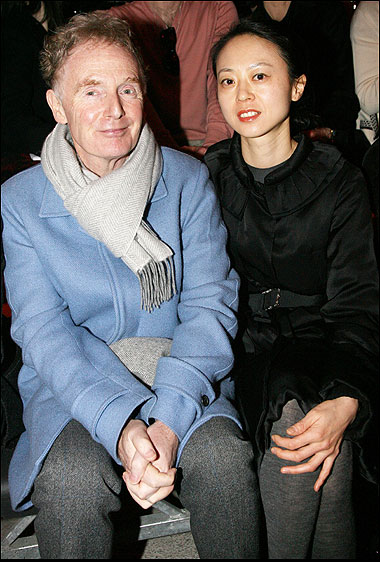

Even Young Kim, the woman with whom he spent his final 12 years, meant less to him than the shadow of a tormented and fractured relationship with the woman he lost his virginity to.

It was a testament to his legacy of familial dysfunction, the comfort he found in disorder – even as it resulted in a broke home and the broken hearts of his partner and child.

When McLaren died in 2010 of a rare form of cancer, he left one final twist of the knife through the words of his will:

“I hereby appoint as my sole heir and executor of my will Ms Young Kim… I exclude my son from any inheritance.”

A devastated Joe challenged the will in court but failed to overturn the decision, ensuring the dysfunction McLaren so savoured would linger long after his death.

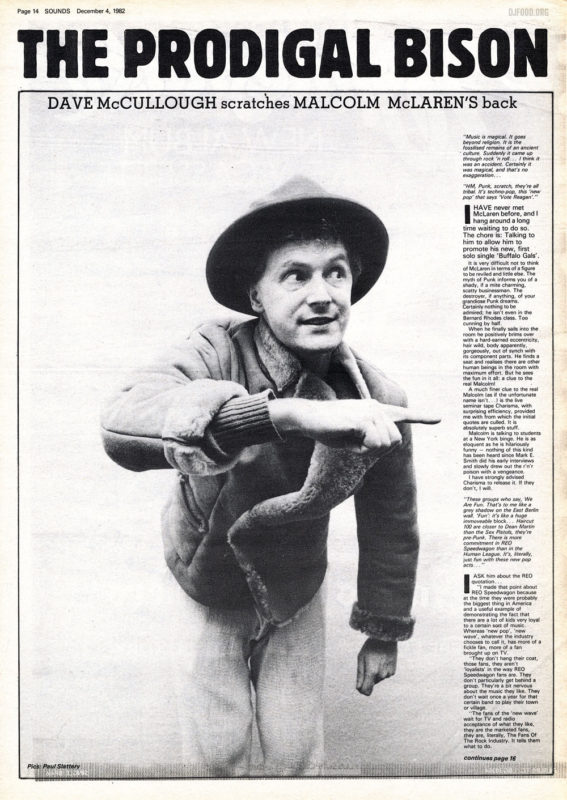

And yet there is poetic justice in the life of McLaren, who found little professional success after separating from Westwood: he managed bands Adam Ant and Bow Wow Wow, helped to pioneer scratch and hip-hop through hit singles with group Buffalo Girls, but after that… nothing.

It should hardly be surprising that a man who embraced chaos and dysfunction could never aspire to anything more than the sum of his parts.

Artists must continuously evolve in some form to maintain relevancy, but the core of McLaren’s punk rock ethos is the antithesis – more concerned with tearing down than building up or evolving.

While contemporaries like Vivienne Westwood have found continued success in their exploration of what punk can represent – a social force for change rather than a battle cry for chaos – McLaren remained myopic for decades, unable to escape a subculture predicated on continued destruction.

The man who founded punk rock to “get rich,” in his own words, left a vicious feud between his family and partner for an estate worth a little over $250,000.

By contrast, Vivienne Westwood has a net worth of hundreds of millions of dollars. Even Joe – who endured the most determined and gleeful of absentee parenting – rose to greater heights of success than his father: after founding lingerie brand Agent Provocateur, the son of McLaren and Westwood is worth tens of millions of dollars himself.

Still, if his only legacy to the world was marketing punk to mainstream culture, it remains a more important feat than countless billions can claim.

Punk is a subculture that will continue to exist for decades. It has become a staple of fashion and culture: an ideology unafraid to stick a thumb in the eye of the established order, shaking the status quo or defying authority for the simple thrill of rebellion.

And like all great self-promoters, McLaren knew his genius would only be appreciated after he was gone. As it reads on his headstone, “better to be a spectacular failure than a benign success.”

“People are beginning to learn the truth about punk, and how instrumental I was in the development of it. That will change the way people will think of me. That will be in the obituaries.”

Check back every Tuesday for the latest teaser for FIB and Style Planet TV’s newest docuseries, Renegades.

Written by: Charlie O’Brien

Edited by: Jess Bregenhoj