Is the youth of today fatalistic with a Charles Bronson-level death wish? Or has it all been blown out of proportion?

It would be understandable to say that today’s generation of youths have a certain fatalism. With the boom in dystopic young adult fiction like Hunger Games and Maze Runner, high suicide rates (in 2018, 38.4% of deaths in the 15-24 age group were suicide), and the ever-tightening grasp of capitalism increasing the wealth gap, we have plenty to be fatalistic about. But arguably, these are only new symptoms.

Even though the millenial generation currently graduating into adulthood appear prepared for – or even welcoming of – dark times ahead, it’s misconstrued. Rather, a new style of humour emerging from internet culture has twisted the perception of this generation.

The End of the World: Are We There Yet?

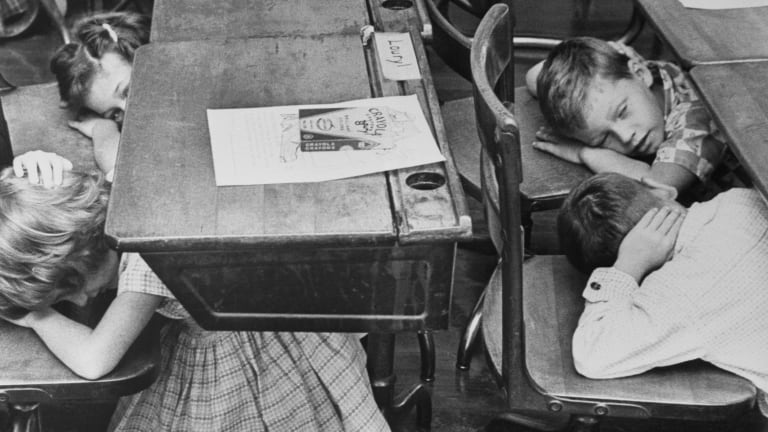

The truth is, thirty to forty years ago, the youngest generation were being indoctrinated into that same fear of nuclear war the preceding generation felt. The art of that period reflects this disposition. Remember Leonard Cohen’s ‘First We Take Manhattan’, that pseudo synth-pop manifesto of a terrorist who marries his radical beliefs to a capitalistic edge

“I’m guided by a signal in the heavens / I’m guided by this birthmark on my skin / I’m guided by the beauty of our weapons / First we take Manhattan, then we take Berlin.”

Or the John Milius war film Red Dawn, which follows a group of high school students (Patrick Swayze, C. Thomas Howell, Charlie Sheen and other 80s stars) who enter guerrilla warfare after an invasion by Cubans and Nicaraguans in their small Colorado town. A sort-of ironic twist on the Viet Cong during the Vietnam War (which Milius also famously adapted in his screenplay of Apocalypse Now), these high school children are forced by circumstance into World War III, with a good deal of them dying in battle. The film ends with a shot of the memorial for the dead, saying,

“In the early days of World War III, guerrillas – mostly children – placed the names of their lost upon this rock. They fought here alone and gave up their lives, so “that this nation shall not perish from the earth.””

With such a focus on threats from without, especially when focussing on the consumer and the student, previous generations would certainly have had a fatalistic view of the future. The 80s presented a revitalised fear of nuclear war that hadn’t been so heightened since the Cuban missile crisis, nor as socially prevalent since the days of ‘Duck and Cover’.

This empathetic understanding of the fatalism of each generation extends further, with the Vietnam War, the Kent State Massacre, and Watergate in the 70s. The decade earlier, political assassinations were rampart such as both Kennedy’s, Dr. Martin Luther King, and Malcolm X. Arguably, the youth of that era also felt somewhat despondent with the prospects of tomorrow. Paul Simon certainly was when he penned such songs as ‘He Was My Brother’, about friend and fellow college student Andrew Goodman, one of the victims in the Freedom Summer murders, or the wider feeling of detachment in ‘I Am a Rock.’

Perhaps then, describing the younger generation of today as fatalists is a misnomer. Perhaps the characterisation of youths as depressive, suicidal, anxious, nihilistic, and cynical is misattributed by media produced outside this generation’s input. Instead, these symptoms present a new form of communication.

Arguably one of the greatest evolutions of the internet is the meme. It invades nearly every corner of the internet and has defined social media. Facebook and Instagram, once envisioned as forums for personal updating à la the diary, now are predominantly a trading ground for memes. So, how can mediums such as film and literature hope to capture the nuances of the younger generation without understanding the communicative function of a meme?

That being said, misrepresentation doesn’t make these mediums obsolete. Films like Eighth Grade and Boyhood captured the culture of a generation across the past twenty years, to widespread critical and audience acclaim. Musicians of our gen also have arguably the greatest impact on audiences when compared to any other producer of art, especially those with dedicated followings such as Taylor Swift or Kanye West.

“I’m Very Sorry Baby, Doesn’t Look Like Me At All”: Questioning Perspectives and Assessing Results

As part of this article, the writing staff at Fashion Industry Broadcast filled a questionnaire to evaluate their world-views. The choice of questions was to reflect on perception without being too invasive, not for fear of offence but rather to ensure more honest, less guarded answers.

Seven staff members – all millenials – were asked for their answers, a selection of which follow:

- Where do you see yourself in five years? What about in five months?

Vishaal: “In five years, I see myself at a news broadcasting corporation, working as a journalist. In five months, I will be aiming to pass all of my units to graduate uni. Also, will be preparing myself for an upcoming internship.”

- Do you see yourself as a religious individual? Is your religion a defining feature of your identity?

Alan: “I am technically Christian (been baptised and went to Catholic schools), but religion is not a defining feature of my identity as an adult. I don’t go to church, but I respect people who do.”

- Do you see yourself as a political individual? Is your politics a defining feature of your identity?

Andrew: “At times yes, it’s frustrating to learn or talk about politics because it seems so far removed from the straightforward and mostly obvious way things should be done. The pettiness in Australian politics is infuriating when we have bigger issues to take care of but we are so slow, that getting something done is an uphill battle.”

- How do you see yourself in relation to your country? Do you ever feel proud to be a citizen?

Vishaal: “Although I was ultimately raised here, I do still sometimes feel like a ‘visitor’ – despite being a citizen. Coming from Fiji, Australia provides a lot more opportunities and I do feel proud to be an Australian citizen.”

Andrew: “I have always been conflicted about the pride I have to be a citizen. On one hand yes, Australia is great, we have so many freedoms and protections that other countries only dream of. But being a white male, its shit to see other people of the same identity not embracing the real Australian way.

“Australian culture isn’t eating a lamington, it’s the fact that we have so many cultures living together sharing traditions, culture, food, music and customs that the lines get blurred… I’m waiting for Australia to become a leader in something, a nation the rest of the world looks to for. A sector of science, a leader in connectivity, something to hold for being forward thinking.”

- Do you feel as if you can represent yourself openly? Does your name, your clothes, your speech patterns, etc. accurately depict who you see yourself as or do you feel it is a performance?

Kirsta: “Yes, around the people I’m close to I can freely express myself, but with strangers I act more reserved.”

Alan: “I’m finding it easier to express myself (dressing, writing, and talking) as I get older. There’s definitely some doubt and awkwardness from time to time, but that’s life. Most of the time I act in a way that is true to myself, except when I’m overwhelmed.”

- How do you view art? Is it an escapist entertainment, an important form of expression, or a mixture of the two? Does it differ between mediums, e.g. music, film, paintings, literature?

Grace: “Art is an escape and a form of expression. Music is a form of expression and film; literature are the best forms of escapism. I also learn a lot from literature, films, television etc.”

Gabriel: “I enjoy all art, and I feel like each medium is different but has the same purpose. The purpose of expression to help us express ourselves and others.”

- What kind of entertainment do you like best, e.g. genres, musicians, directors, writers?

Alan: “I watch a lot of movies and shows (film is the earliest passion of mine) and enjoy reading all sorts of books. I also listen to music and play guitar.”

- Do you often find yourself reading the news, or do you prefer to minimize your news media intake to just headlines and word-of-mouth?

Vishaal: “I find myself reading the news in order to gain a personal perspective on the happenings. Word of mouth can sometimes be unreliable in the day of social media.”

Annika: “I do… but I also try to minimise and consume things that nourish me more.”

- How do you stay optimistic about the future? Are there certain quotes you hold close, your relationships to others, career aspirations, etc.?

Kirsta: “Yes, I try to enjoy the little things in life and acknowledge that I can only control some things in my life. Life is about perseverance.”

… The answers for these questions hardly present a fatalistic perspective amongst my generation. Rather, they display a worldview that is primarily optimistic. Possessing a critical lens doesn’t define an individual’s perspective as overtly fatalistic, nihilistic, or cynical. It shows a well-rounded sense of self, a desire for identity and agency.

I’d argue instead that these labels are applied incorrectly, with certain behaviours and mannerisms inflated by an out-of-touch older generation. Remember, even though dystopic franchises like Hunger Games and Maze Runner had strong success among their target audience, their authors were ages 46 and 37 respectively. Books and films depicting dystopic societies with strong class systems are the classic melodramatic representations of schooling that the entertainment industry gravitates to.

I’d also argue that this label doesn’t overly bother the intended recipients, because those who assign the label assign it so incorrectly that we have to wonder, “Why take them seriously?”

Subscribe to FIB’s Weekly Alchemy Report for your weekly dose of music, fashion and pop culture news!