The innovator, the originator, the architect of rock ‘n’ roll died of bone cancer, age 87.

Little Richard, one of the most influential performers and pioneers of rock ‘n’ roll in the 1950s, died May 9th from bone cancer. The singer, beyond the influence of his music, brought an unrivalled showmanship to the genre that neither Elvis nor Chuck Berry could compete with. With a stage persona that overshadowed the real Richard Penniman, Little Richard was instrumental in paving the way for contemporary singers and concerts.

The Life of Little Richard

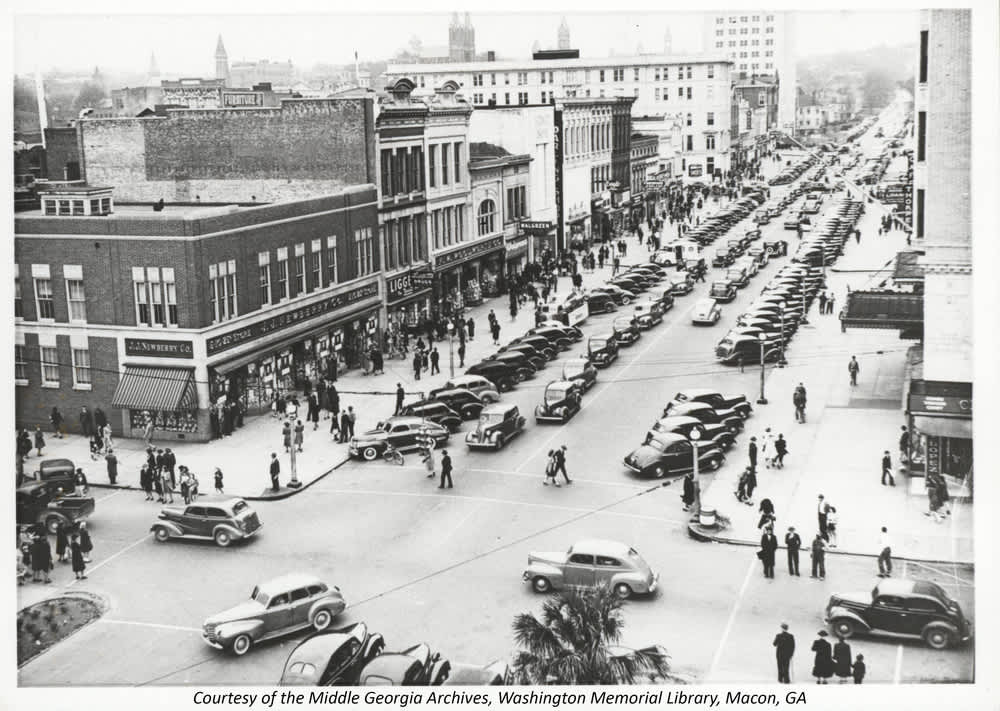

Little Richard, born as Richard Penniman on December 5th 1932 in Macon, Georgia, was the son of a deacon and moonshiner, picking up a love of singing from Pentecostal choirs and the blues and gospel pioneer Sister Rosetta Tharpe, who he opened for at the age of 14.

He joined travelling medicine shows, participating in vaudeville, minstrelsy, and midnight rambles. It was here that Penniman was introduced to R&B music, a genre his family had forbidden as the devil’s music. While on the road, Richard also began to learn the importance of costuming and stage persona, often dressing in drag and picking up his now iconic hairdo and moustache. In an interview with David Letterman in 1982, Richard explained the influence of his costuming and persona:

“Well, it was strange because didn’t nobody else have nerve enough to wear what I was wearin’. I believed a lot of people wanted to look like I looked but they didn’t know how to put it on.”

After struggling to enter the music industry, Richard finally broke through with his most well-known song ‘Tutti Frutti’ and was launched to the heights of stardom alongside fellow rock ‘n’ rollers Elvis Presley and Chuck Berry. Richard held the spotlight between 1955 and 1957 until when on tour with Gene Vincent and Eddie Cochran in Australia, his plane experienced some difficulties between Melbourne and Sydney. When he saw a fireball coming across the sky after his Sydney performance, Little Richard took it as a sign of God, an instruction to renounce secular music and return to his Christian roots.

When he returned to the states, Little Richard repented and left the music business, instead enrolling in Oakwood College in Alabama to study theology. During this time, Richard lost the royalties to his music when he ended his contract with his record label. During his Letterman appearance, Richard stated:

“I made a lot of money, but I was cheated, I was used, I was exploited, y’know. The fella came to Macon, Georgia and got me and told me he’d make me a star. I wanted to be a star more than I got the money. So he’s rich, I didn’t get rich from it.”

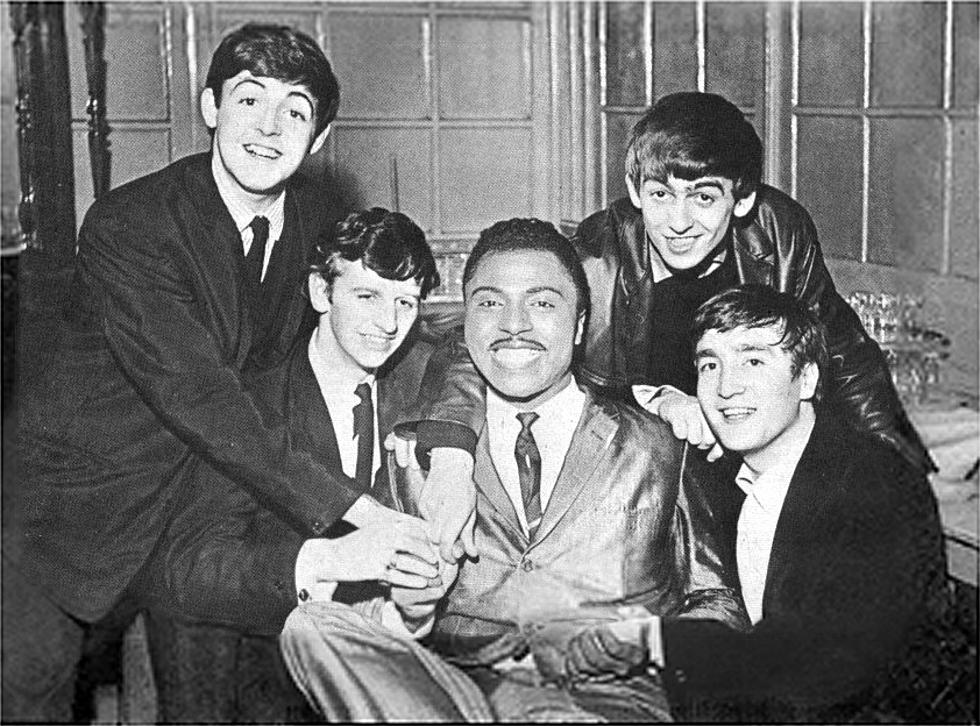

Eventually, Richard returned to music in the 1960s to further career success, working with The Rolling Stones, The Beatles, Bo Diddley, and The Everly Brothers, before returning to evangelism again by the 1980s and having another comeback by the 1990s.

By the 2000s, Little Richard’s legacy was sealed in history as one of the greats of rock music. In 2000, the television movie Little Richard, starring Leon, tracked his early life in Macon until his comeback in the early 1960s. Richard diversified his appearances in media, contributing to a Johnny Cash tribute album in 2002, advertisements for Tostitos and GEICO, as a guest judge on the reality show Celebrity Duets, and performed at the 2008 Grammys. Richard even continued touring until 2013, when he stated in an interview with Rolling Stone that due to health concerns he would cease, “I’m in pain 24 hours a day.” Little Richard performed his last concert in 2014, in Murfreesboro, TN.

A Brief History of Rock ‘n’ Roll

If there’s one word to describe the music of Little Richard, it’s urgency. Looking at the compilation album The Very Best of Little Richard, all his songs are relatively short (although this was standard for the time), the longest being ‘Goin’ Home Tomorrow’ at 3:16, the shortest, ‘Tutti Frutti – Live’, at 1:47. Listening to ‘Rip It Up’ – a chart-topper from 1956 that’s been covered by everyone from Bill Haley and His Comets to Alvin and the Chipmunks – you can understand how Little Richard’s urgency elevated him into the forefront of the cultural consciousness.

Well, it’s Saturday night and I just got paid,

Fool about my money, don’t try to save,

My heart says go go, have a time,

‘Cause it’s Saturday night and I’m feelin’ fine

from ‘Rip It Up’

Verses like this encapsulate the rock ‘n’ roll experience of the 1950s. As the Cold War takes off and US citizens are reminded to “Duck and Cover” under desks and picnic blankets when Soviet bombs drop in their small towns, rock ‘n’ roll digs into this subconscious urgency to live life before a nuclear winter sets in. Drawing from traditional black music, the roots for rock were dispersed during the Second Great Migration that began in 1940 and saw the migration of 4.3 million African Americans from the South to the Northeast, Midwest, and West to escape the oppressive Jim Crow laws in the South. It saw the beginning of the end of the Black Belt, a Southern geological region characterised by fertile black soil, where plantations were often based and workers were beginning to be replaced with machinery.

But with the Second Great Migration came an integration of cultures as both black and white people began to live and work in close proximity in cities such as Los Angeles, Seattle, and Phoenix. As such, a musical crossover of styles began and radio stations began to reflect this. Many early rock ‘n’ roll groups were made of black musicians who married different styles such as blues, country, the electric blues, and jazz to create what we now know as rock ‘n’ roll. With the rising popularity of this genre, record companies began to have white musicians cover these songs to circumvent promoting and advancing black groups when established white groups already had popularity and mass appeal in the South.

Despite this, black musicians prospered in rock ‘n’ roll as many white musicians lacked the riveting performance style of their counterparts. It wasn’t until Elvis Presley, who incorporated the styles of black musicians, that white musicians could physically appeal to the crowd as other African American performers could. Other popular white musicians in rock ‘n’ roll also included Bill Haley and His Comets, whose song ‘Rock Around the Clock’ is now considered the first widely popular rock ‘n’ roll song, and Buddy Holly, whose rockabilly style was essentially rock ‘n’ roll for white audiences, combining hillbilly country with rock ‘n’ roll. Other notable rockabilly performers include Jerry Lee Lewis, Carl Perkins, and Johnny Cash.

As a Georgian native, Little Richard’s family never took part in the Second Great Migration or experienced the wide integration of musical styles that occurred in the city. Rather, Little Richard developed his rock ‘n’ roll performances from gospel music and his idols such as Sister Rosetta Tharpe. It also may explain why Little Richard believed himself to be the only true originator of rock ‘n’ roll when Tharpe, Ike Turner, and Fats Domino also have valid claims to that title.

“Talkin’ bout the midnight rambler”

A good case for why Little Richard is the originator of rock ‘n’ roll likely stems from his performances onstage. While Elvis and Chuck Berry each contributed significantly to the performance aspect of rock music, Little Richard arguably perfected it with his outrageous persona. His high-pitched singing, higher hairstyle, and a skill for scat singing that could rival Cab Calloway, Little Richard employed it all to service his own manic rhythm and lending his 1950s music that aforementioned urgency.

By the time the 1960s and 70s rolled around and Little Richard had spent some time in the ministry, his rock ‘n’ roll had become wilder, more cathartic to himself. His costumes were vibrant relics of the psychedelic era crossed with Elvis-style rhinestone jumpsuits. Whereas once dressed in suits, Richard now dressed in ways that evoked his experiences in the carnival and midnight rambles of his youth.

It’s here, in this ritualistic resurrection of musical legacy, that the success of Little Richard as a performer can be understood. The concept of the midnight ramble stemmed from the Reconstruction, the period of restoration and recovery that followed the American Civil War, when what we understand now as contemporary American culture originated from, particularly traditional folk music. Levon Helm, the drummer of Canadian-American group The Band, explained this concept thoroughly in Martin Scorsese’s rock concert film The Last Waltz.

“Most of the show stuff though was like traveling shows, like tent shows. One was Walcott’s Rabbit’s Foot Minstrels… you know, they used to have the show start, right, and have the singers and the players and the different parts of the show and the master of ceremonies would come out, y’know, just before the finale and explain that after the finale, after the kids go home, they’d have the midnight ramble, right?… And the songs would get a little bit juicier, the jokes would get a little funnier, and prettiest dancer would really get down and shake it a few times. Lot of the rock ‘n’ roll duck walks and steps and moves came from a lot of that.”

Little Richard in his youth, after being kicked out by his father due to his femininity, joined many traveling shows. In the biography The Life and Times of Little Richard: The Authorized Press, author Charles White recounts through Richard’s own testimony his experiences touring with these shows.

“When I started getting into all this trouble at home, I left and joined up with Dr. Hudson’s Medicine Show. I didn’t tell anybody I was going. I just went. Doc Hudson was out of Macon, and he used to sell snake oil… He had a stage out in the open, and a feller by the name of James would play piano. I would sing “Cal’donia, Cal’donia, what makes your big head so hard?””

From there, Little Richard joined B. Brown and his Orchestra, “I started traveling with them. We went all over Georgia, playing in white clubs, and I would sing ‘Goodnight Irene’ and ‘Mona Lisa’, and all those different kinds of ballads.” Richard also joined other traveling shows like Sugarfoot Sam from Alabam, where Little Richard first began to dress in drag, King Brothers Circus, Tidy Jolly Steppers, L. J. Heath Show, Broadway Follies. It was with the Broadway Follies that Little Richard first met Billy Wright.

“Billy Wright was an entertainer that wore very loud-coloured clothin’, and shoethin’ to match is clothin’, and he wore his hair curled. He influenced me a lot. He really enthused my whole life. I thought he was the most fantastic performer I had ever seen… His makeup was really something. I found out what it was and started using it myself.”

When Little Richard finally left the traveling carnivals and roadshows, he took decades-worth of American performance tradition with him into the mainstream. He revealed the hidden America that rock journalist Greil Marcus would term as “The Old, Weird America” and exposed it to generations of future performers. In this sense, Little Richard truly is the innovator, the originator, the architect of rock ‘n’ roll.

A Legacy of Influence

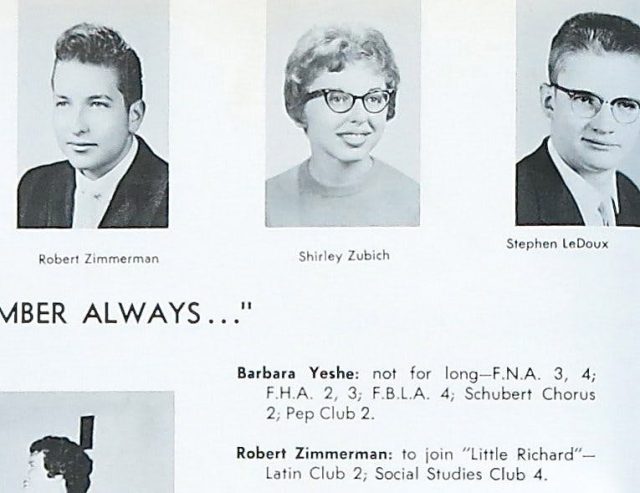

Since arriving on the radio waves with ‘Tutti Frutti’, Little Richard inspired countless musicians in singing style, performance style, and onstage persona. One of the biggest of these musicians is Bob Dylan. In Dylan’s high school yearbook, he had written that he aspired “To join Little Richard.” Before becoming an icon of folk music, Dylan was an ardent fan of rock ‘n’ roll artists like Little Richard, Elvis, and Buddy Holly, even seeing Holly in concert only a few days before he died.

Had Dylan not been as enigmatic as he was, and still is, perhaps Dylan ‘going electric’ would have been an easier transition for his audience with this context in mind. But it’s precisely from Little Richard’s talent for self-mythologising and an engaging stage presence that so inspired Dylan to create his own enigmatic persona.

Dylan’s admiration for Little Richard was so constant that he released a rare statement on social media, commemorating the late legend.

I just heard the news about Little Richard and I’m so grieved. He was my shining star and guiding light back when I was only a little boy. His was the original spirit that moved me to do everything I would do.

— Bob Dylan (@bobdylan) May 9, 2020

In his presence he was always the same Little Richard that I first heard and was awed by growing up and I always was the same little boy. Of course he’ll live forever. But it’s like a part of your life is gone.

— Bob Dylan (@bobdylan) May 9, 2020

The Beatles were also strongly influenced by Little Richard’s music. In White’s biography of Little Richard, Paul McCartney opens with a foreword, saying:

“I have these fantastic memories from an early age, singing ‘Tutti Frutti’ at school – it was a big rave at the time. The first song I ever sang in public was ‘Long Tall Sally,’ in a Butlins holiday talent competition! When the Beatles were first starting we performed with Richard in Liverpool and Hamburg, and we became close friends. Richard is one of the greatest kings of Rock ‘n’ Roll. He’s a great guy and he’s my friend today.”

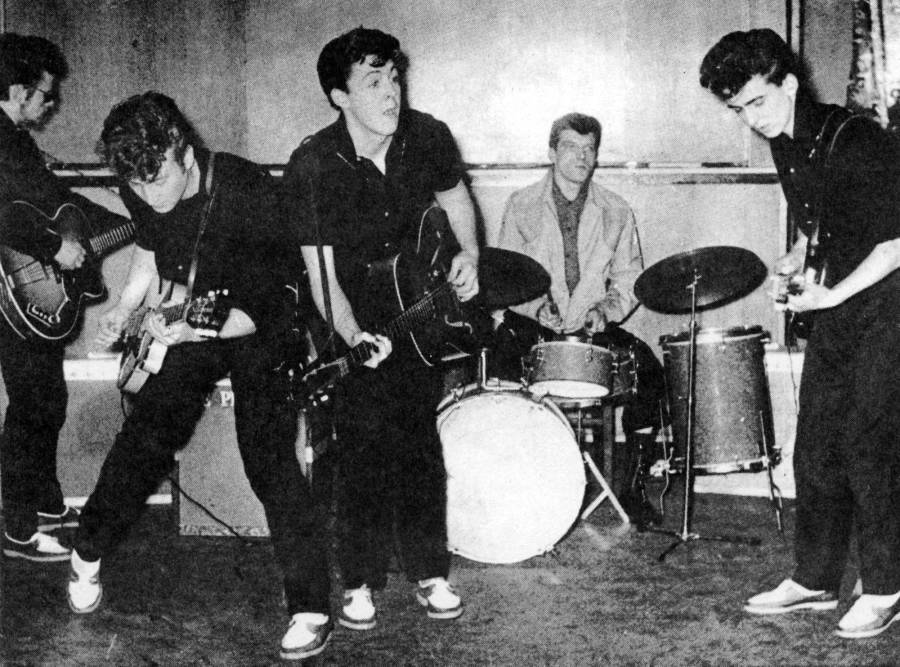

Richard was indeed a strong influence on the musical choices of the early Beatles setlists. Back when the Beatles had a residency in Hamburg with German club owner Bruno Koschmider, when the Beatles included Stuart Sutcliffe on bass and Pete Best on drums, adopting Richard’s style only improved them. Little Richard’s eccentricity and sexuality was a valuable addition to their Hamburg performances in the red-light district.

The Beatles also adopted a similar hairstyle to Richard’s popular in Hamburg known as the ‘exi’ style (short for existentialist) that was introduced to them by friend and frequent photographer Astrid Kirchherr, cutting their hair similarly to the Liverpool Teddy Boy style and to evoke an existentialist, rebel subculture. While their dress style was not as obviously flamboyant as Little Richard’s, their dark leather and jeans were an attempt to distance themselves from their oppressive high school culture.

David Bowie and Prince were also clearly influenced by the singer. Bowie, an icon of glam rock, imparted a lot of Richard’s predilection for costuming and stage persona in his own performances, likening the rock ‘n’ roll singer’s talents to like hearing “the voice of God.” In an interview with Rolling Stone, Bowie stated “Little Richard was just unreal. Unreal. Man, we’d never seen anything like that.” Prince was the inheritor to Little Richard’s persona, with his own pencil-thin moustache, heightened hairstyle, and androgynous appearance. It was a comparison that Richard himself made, telling Joan Rivers in 1989, “Prince is the Little Richard of his generation.”

Other musical icons also were strongly inspired by Little Richard. James Brown, the Godfather of Soul, befriended Richard during the mid-50s when they shared the same manager, where Brown likely learned the value of flamboyance through his onstage impersonations of the rock ‘n’ roll singer. Jimi Hendrix had a short-lived stint in Richard’s band playing guitar, until the clash of personalities between him and Richard ended with Hendrix’s firing. Mick Jagger learnt his strut from watching Little Richard’s performances when touring in the early 1960s. Elton John also employed a similar reliance on costuming to enhance his concerts.

A Legacy of Controversy

Another aspect to Little Richard that separated him from his peers was his controversial personal life. Richard, a self-confessed homosexual, had a complex relationship to his sexual preferences. He stated to Letterman:

“I’m not gay now, but y’know I was gay all my life. I believe I was one of the first gay people to come out. But God let me know he made Adam to be with Eve, not Steve.”

In his youth, Richard became involved in voyeurism with a female friend, eventually leading to a three day stay in jail. Even after becoming born again, Richard’s voyeurism persisted, exposing himself to a fellow student while attending Oakwood College that forced him to leave. He was also caught spying on men urinating in a bus station in Long Beach, California.

Richard has called himself heterosexual, homosexual, and omnisexual throughout his career. After becoming born again a second time in the 1980s, Richard denounced homosexuality as an affliction, saying in White’s biography “Homosexuality is contagious. It’s not something you’re born with. It’s contagious.” To contextualise this dissenting perception of homosexuality, it’s worth looking at how Richard discussed the culture of sex in Macon growing up.

Richard recounted to White how older women would sleep with him, how another hung around school grounds by night and had sexual relations with several boys at a time, including Richard. He described his first homosexual experiences with family friends’ who would pay him for sexual services. How white men would prowl African American neighborhoods, including Richard’s, picking up young black men and taking them to the woods for sexual services. How friends who underwent similar abuse pressured Richard into normalizing this behaviour.

His story of sexual abuse isn’t unique to a localized region or time period. The systematic abuse of young black men continues to be prevalent today, a fact that is predominantly ignored by the mainstream media. While Richard’s personal history is no excuse for the severity of his comments against the gay and transgender community, the abuse he suffered does provide valuable context to a behaviour of discrimination against marginalized communities.

A Legacy of Individualism

Little Richard was a complex figure in contemporary music history. He was egocentric and discriminatory, but he was also charismatic and captivating. On-stage, he was an unrivalled performer of rock ‘n’ roll that inspired countless singers and musicians with his eccentricity, persona, and vocal skill. Off-stage, he could be homophobic with a problematic relationship to alcohol and drugs.

But at the core of Little Richard, his long-standing relationship to religion guided his morality for decades, despite Christianity’s denouncement of homosexuality. He preached to both small-town churches and filled auditoriums, seeking to unite all races under God’s love. Richard also officiated weddings, preached at funerals, and helped raise funds to rebuild playgrounds after Hurricane Katrina.

Little Richard’s death marks the end of an era, the last of a generation of classic rock ‘n’ roll artists who revolutionized music in the mid-20th century. But his work will live on through the music and performance of his successors and followers.

Subscribe to FIB’s Weekly Alchemy Report for your weekly dose of music, fashion and pop culture news!