After a lengthy hiatus thanks to old mate ‘Rona, Australians can finally breathe a sigh of relief. The Footy is back! Whether your preference is NRL, AFL or Union, loving a sport with an oval shaped ball and men wearing short shorts tighter than my pony tail in year 7 is Just. Bloody. ‘Strayan.

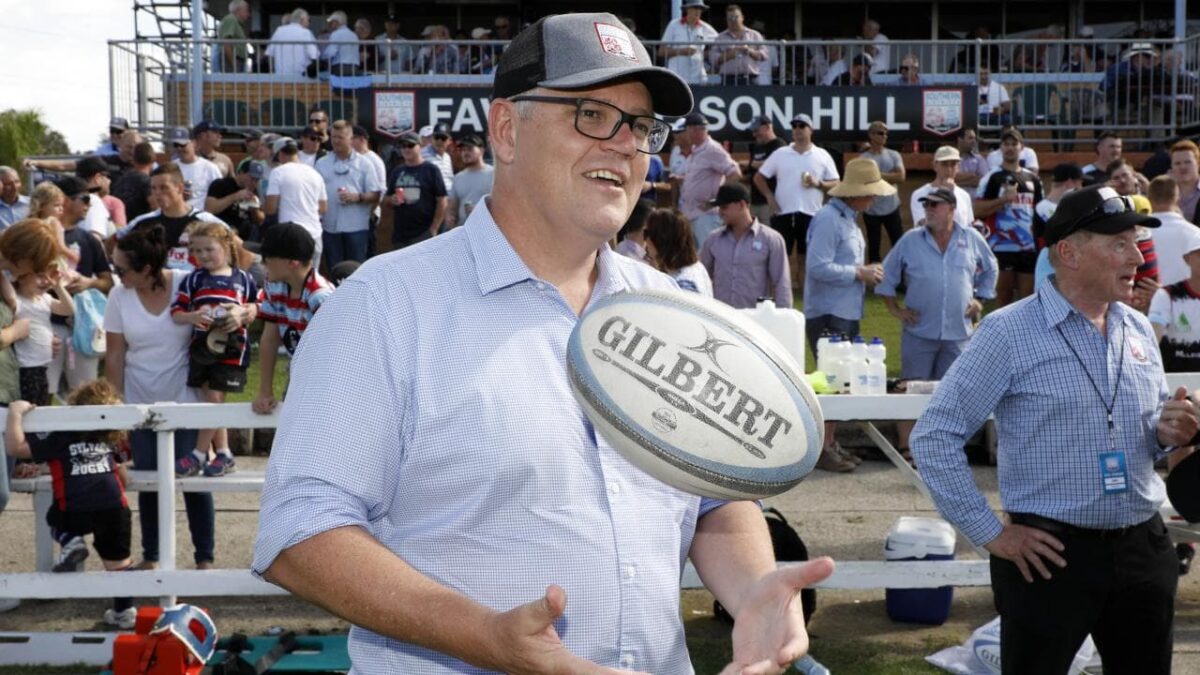

Footy is an engrained part of our culture, and if you’re not on the bandwagon, then you’re probably not on #teamAustralia. In fact, “love it or leave it” is a pretty common moniker from footy fans on Facebook. And when the Coronavirus first came knocking on our doorstep, it was a rugby league game which was the apple of our PM’s eyes. Choosing to attend an NRL match despite impeding state and federal restrictions.

“The fact that I would still be going on Saturday speaks not just to my passion for my beloved Sharks; it might be the last game I get to go to for a long time,” said Scott Morrison.

Fast forward to this month, when thousands showed up to protest for the Black Lives Matter movement, and footy fans were pissed. If protestors could exercise their democratic right to advocate for basic human rights, then why could they not attend a football match? After all, it is a rudimentary part of being Aussie.

Of course, there is no mention of the fact that one of the ‘strongest’ facets of our culture is one that largely sidelines women. Football players are disproportionately accused of sexual assault compared to other professions. Domestic violence rates spike on game night and gambling and binge drinking are all par of the course. Although Erin Molan’s presence apparently means that this issue is fixed.

Similarly, sledging, hazing and testosterone fuelled fights are all just ‘apart of the game’. Never mind the fact that sometimes this means that racist and homophobic language is allowed to infect a club unchecked. Think Heritier Lumumba enduring the nickname ‘Chimp’ for the entire ten years he played for Collingwood.

Of course, footy also brings a lot of good to our country. In January, the 16 NRL teams all pitched in to raise money for the bushfire relief funds. Similarly, the AFL raised $8 million dollars for the same cause. And just this month, Richmond and Collingwood took a knee in support of the Black Lives Matter movement. A massive display of progress since the Heritier Lumumbae days.

But, there there is no denying the fact that there is an underbelly of toxicity to the sport. However, it is not footy alone which has this affect on our society. Studies show that domestic violence rates rise during pretty much any televised sporting game on Australian television. And, racism and sexism are as historically intertwined with sport as they are with our culture.

In 1980, before Evonne Goolagong’s Wimbledon final, an Australian Premier actually said that he hoped she “wouldn’t go walkabout like some old boong.” And in 2006, the Australian cricket team was investigated for alleged racial slurs thrown at the black members of the South African team.

So with such a complex history, it begs the question: Why is Australia so obsessed with sport?

Where it began

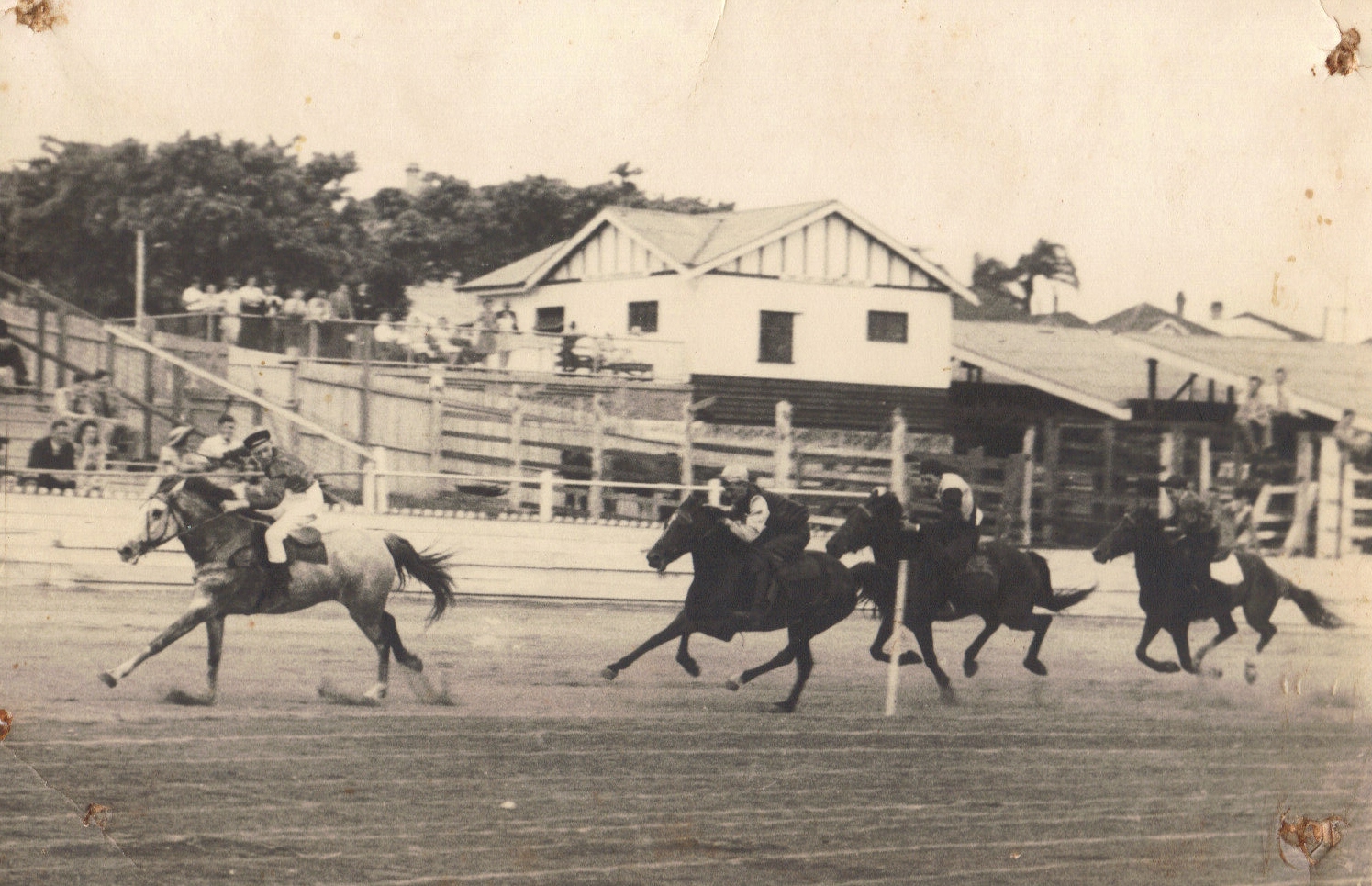

Competitive sport first came to Australia in 1810 when the first athletics tournament was held. Soon afterwards, cricket games, horse racing and sailing competitions followed. Three sports that are joined by one common thread; aristocracy.

So while the upper class could participate in these activities, the working class were encouraged to participate in a sport of their own, gambling.

Horse racing especially became a hub where the different classes could interact across class-lines, except that while one faction was profiting from the event, the other was losing their hard-earned (at below minimum wage) cash. And you can bet (Try Sportsbet) that women or people of colour at the races were few and far between.

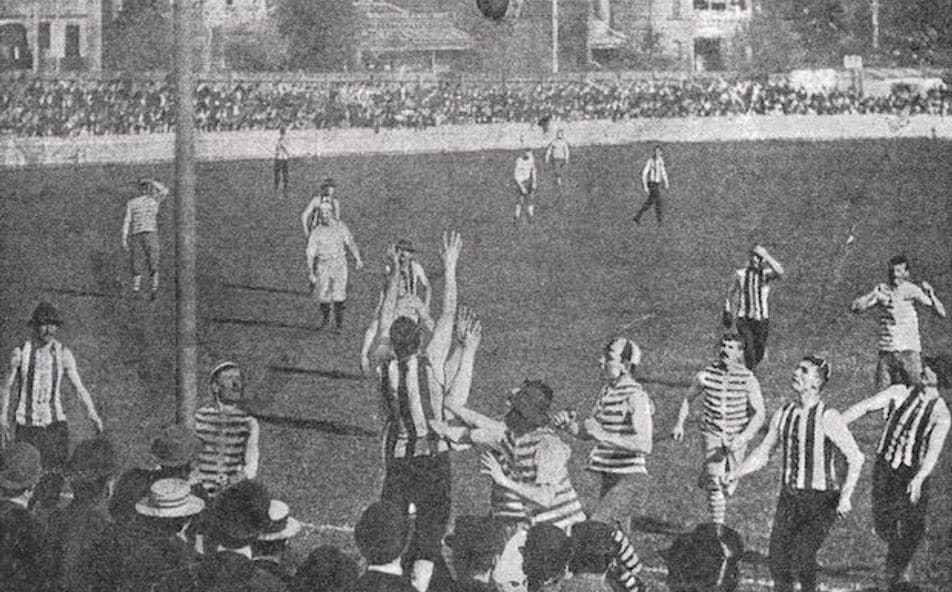

Early forms of rugby and AFL emerged in the 1850’s, and because they only required a roundish ball and a small patch of grass, they quickly became the game of the every-man. Eventually official games progressed, and Australians soon realised that football was an agent of equalisation. On the field, wealth, privilege and sometimes even race no longer mattered. Your team mattered. Winning mattered.

To many, football represented more than just a game, and so began the long history of Australians tying their identity to a sport.

Women On The Sideline

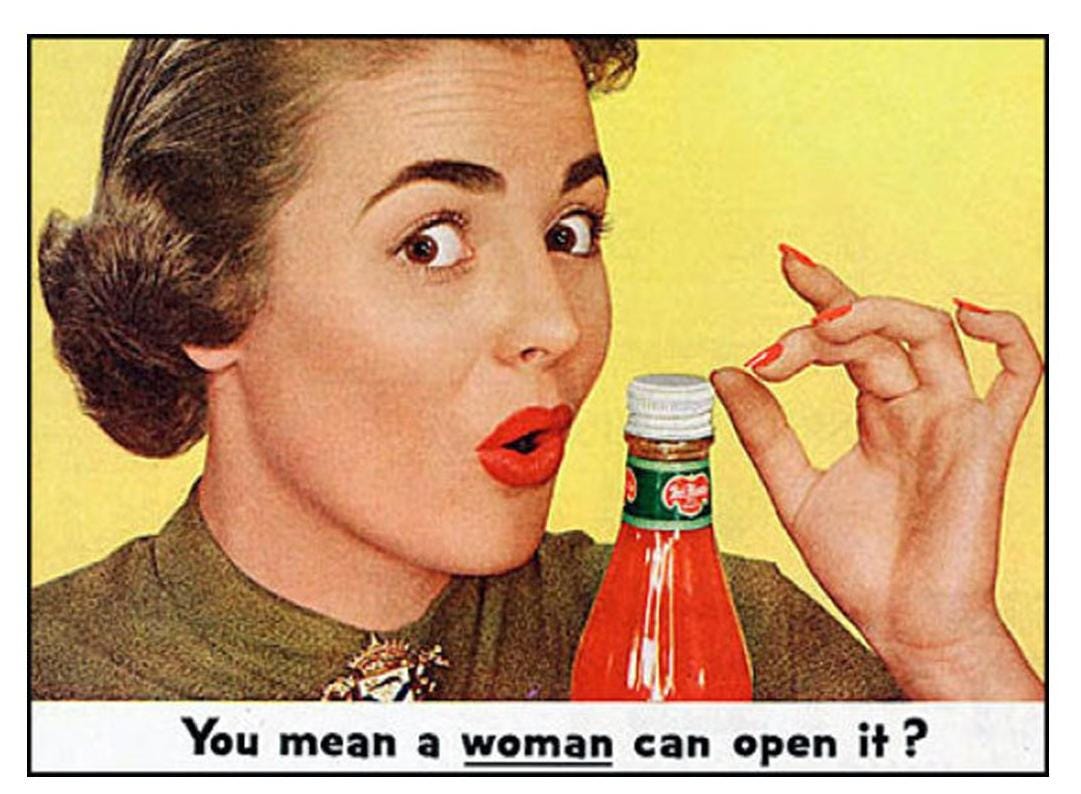

The fact that sport has the power to erase social hierarchies is part of what makes it so great. Except that when I say the ‘every-man game’, I mean it. In 1922 an Australian committee decided that football was “completely medically inappropriate for girls to play”. Sports that women were allowed to participate in included swimming, rowing, cycling and horseback riding. As long as they were not done in an overly competitive manner.

It wasn’t until post world war two that womens sport really began to gain traction as a valid outlet. During the war, Australia was one of the few countries where womens sport organisations held competitions. This structure survived the post-war period and is the foundation for the competitions we have today.

A black mark on our history

As much as we like to think that we, as a country, have moved on from the marginalised origins of sport in Australia, sometimes it is all to clear that we haven’t. And no, I’m not talking about the ball tampering scandal which seemed to induce an identity crisis amongst so many Aussies. I’m talking about Adam Goodes.

Goodes in an indigenous Australian AFL player who holds an elite place in the sports history. He is a Brownlow Medallist, dual premiership player and a four-time All-Australian. He was also the target of sustained racial abuse during his tenure as a player.

The barrage of abuse began when a 13-year-old Collingwood supporter called Goodes an ‘ape’ at the AFL’s annual indigenous round. Upon hearing the comment, Goodes indicated for security to remove the fan. In the days following, Goodes revealed that the comments had left him “gutted” and that he had “never been more hurt”. Regardless, he asked the public to show the fan kindness, rather than attack her.

However, Goodes move to remove the girl unlocked a reaction from the Australian public that has, in hindsight, been categorically defined as racist. Goodes was repeatedly and loudly booed by opposition fans at most matches. Which only intensified during a match in 2015, when Goodes celebrated a goal by performing an indigenous war dance in which he mimed throwing a spear in the direction of the Carlton cheer squad.

Goodes retired at the end of the 2015 season, owing to the stress of the booing and attention. Four years later, on the eve of the documentary ‘The Australian Dream’, the AFL and all of it’s 18 clubs released an unreserved apology for the sustained racism Goodes endured.

“Adam, who represents so much that is good and unique about our game, was subject to treatment that drove him from football. The game did not do enough to stand with him, and call it out. Failure to call out racism and not standing up for one of our own let down all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander players, past and present. Our game is about belonging. We want all Australians to feel they belong and that they have a stake in the game. We will not achieve this while racism and discrimination exists in our game… We will stand strongly with all in the football community who experience racism or discrimination. We are unified on this, and never want to see the mistakes of the past repeated”.

The treatment of Goodes speaks to a greater problem with sport, race and Australian culture. In 1995, sports historian Colin Tatz said “they’re Australians when they’re winning, and Aborigines at other times”. This sentiment is still true today.

Goodes overstepped the expectations outlined for him as an indigenous sports star. He was not suppose to have autonomy, but rather be grateful for the opportunities he was given. For having the audacity to be offended, he was punished.

If This Is Our Identity, Then Where Is It Leading Us?

The good news is, things are getting better. Because sport is so closely entwined with our national image, it means that it is often a reflection of our society.

If there’s anything the Me Too Movement and the Black Lives Matter Movement have taught us in the last five years, it is that there is still systematic oppression within Western society, and that marginalised groups are not experiencing equality. But, thanks to these movements, things are changing.

In 2017, the AFL introduced a premier womens competition, which has now grown from eight teams to 10. In 2018, the NRL followed with four teams. Both competitions are televised on free-to-air TV and Fox.

After years of scrutiny, in 2019 Football Federation Australia and Professional Footballers Australia put in place a system to ensure that the Matilda’s will receive the same pay as the Socceroos. They will also experience the same off-field benefits such as business class flights, training facilities and specialist performance support staff. Considering the fact that the Matilda’s have been far more successful than the Socceroos in recent times, these developments are a very welcome injunction.

And now, following the remarkable social change in response to the BLM protests across the world, our sporting clubs are following suit. This season, The AFL has a new footy show called ‘Yokayi Footy’. An indigenous footy show championing young, diverse players and perspectives. This is hugely significant as it gives young indigenous players a safe place for their voice to be heard.

Clubs across the NRL have followed the AFL’s lead, and have also taken a knee.

Whether you like it or not, it looks like Australia’s national narrative will always be synonymous with sport. At least now, we are moving towards a more inclusive landscape, where everyone can revel in this national past-time. Not just the ‘every-man’.

Subscribe to FIB’s Weekly Alchemy Report for your weekly dose of music, fashion and pop culture news!