The last two decades have been successful but not incredible for Australian cinema, so what can we expect next and what do we have to fight against to get it?

In 1975, Gough Whitlam implemented the Australian Film Commission. A successor to the Australian Film Development Corporation established by John Gorton, the AFC aimed to promote the creation and distribution of films in Australia whilst also focusing on preserving Australia’s cinematic history.

The AFC was welcome by Australians. Jack Valentini, a motion picture distributor from America, was greeted by 200 protestors on his arrival at the Australian airport. Signs read ‘Cut the US connection’ and ‘We can make our own rubbish, Jack!’. Well and truly, Australians had grown sick of the infiltration of US and British films into our country since at least the 1920’s, and Gough Whitlam’s support for culture and the arts was the tool we needed to start making our own rubbish.

In 2008, the Australian Government merged the Australian Film Commission with Film Australia and Film Finance Corporation Australia to create what we now know as Screen Australia. Screen Australia is the key government funding body for Australian screen productions, and as of 2019 has supplied nearly $76 million in direct funding of films and television.

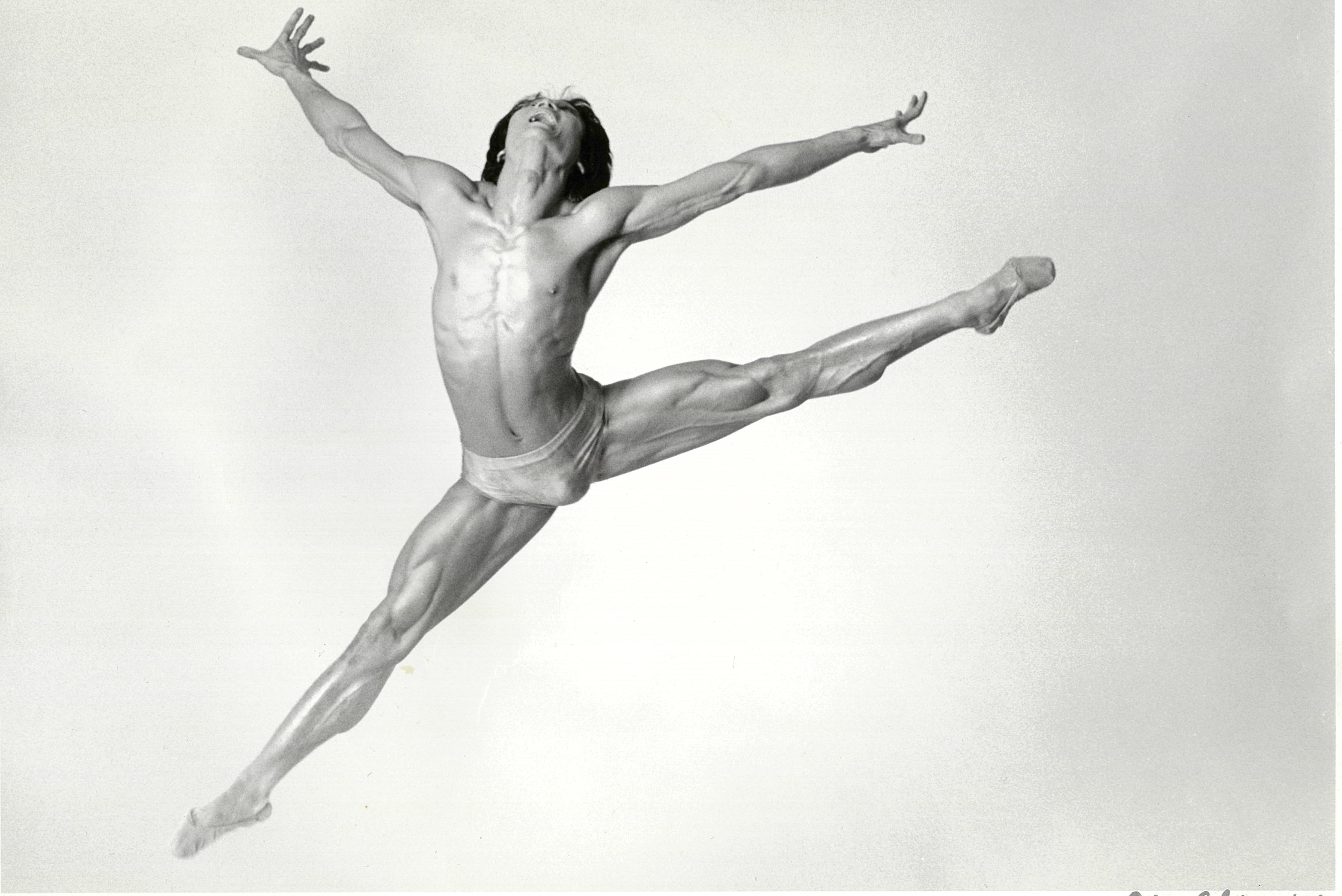

This funding has not gone to waste. From 2008 up until the present day, Australian filmmakers still work steadfastly, aided by the governments financial assistance, to ensure Australian films aren’t written off as they once were. Mao’s Last Dancer, directed by Bruce Beresford and filmed in Sydney, was internationally successful, and became the 12th highest grossing Australian film of all time. 2009 saw the release of Bran Nue Dae, an important film both in terms of Indigenous representation and in an overseas understanding of Australian culture.

Bran Nue Dae, a musical comedy starring such acclaimed actors as Geoffrey Rush, Ernie Dingo and Deborah Mailman as well as musicians Jessica Mauboy, Missy Higgins and Dan Sultan, follows a boy who runs away from his boarding school in Perth and attempts to win back his girlfriend. This simplistic plot is made entertaining not only due to the outstanding musical performances but due to the inherently Australian characteristics of the journey. The open roads and sparse outback, intimidating rural shop owners, long journeys by car through dusty roads; these were once things laughed at by international audiences and treated as basic and boring, yet in Bran Nue Dae they are celebrated as beautiful.

However, not all Australian films depict rural life, as much as overseas audiences like to think this is representative of all Australia. The gritty underbelly of Australian suburbia masked by extravagant homes and lavish living was exposed in the 2010 crime drama Animal Kingdom. Set in Melbourne and based on actual events, the film stars Ben Mendelsohn, Guy Pearce and Jacki Weaver amongst others as members of a wealthy and murderous crime family. Relentless in its brutality and featuring spectacular performances from the cast, Animal Kingdom is a suburban drama that frightens audiences with its portrayal of dangerous suburban living, and is refreshing against so much of the outback driven films released in Australia at the time. The film received universal acclaim both for the performances and the storytelling, and proved to the world Australia still had the motivation to release films just as brilliant as any seen overseas.

In the past ten years these kinds of films, whether they be drama or crime based, have become increasingly popular. Australians enjoy seeing Australian life portrayed accurately and interestingly on screen, and the advancement of technology along with increased funding opportunities has made this possible with growingly creative ventures. Justin Kerzel’s directorial debut Snowtown in 2011 is potentially one of the most shocking Australian films ever made.

Based on a real series of murders in Adelaide during the 1990’s, the film, funded by Screen Australia, featured locals from the area instead of actors. This, along with the bleak landscape of semi-isolated suburbs and an atmospheric, dark cinematography, created a film so brutal it was described by critics as an ‘endurance test’. However, Kerzel’s storytelling shifts in such a way as to portray what can happen to people living in disadvantaged communities rather than being a straightforward crime film. This is what made it a hit amongst sympathetic viewers.

The trend of social realism continued albeit on a lighter note with 2012’s The Sapphires. The Sapphires tells the story of four Indigenous women who travel to Vietnam as a singing group to perform for the troops. Shot in various parts of New South Wales the film had a strong release and received positive reviews, and took a fresh look at the lives of Indigenous Australians in a modern setting. Social themes of a more melancholy note featured in 2015’s Last Cab To Darwin in which a taxi driver travels 3000 kilometres seeking euthanasia.

Another major release of 2015 was Mad Max: Fury Road, the fourth installment in George Miller’s series. Set in a post-apocalyptic world and now starring Tom Hardy as Max, the film depicts a lengthy road battle in a desert wasteland with scarce water and petrol. Without abandoning his Australian roots in terms of environment, Miller introduced Hollywood stars and high action fast-paced themes into the film, with some critics naming it one of the best action films ever made.

Though not prolific by any means nor exceptional for the most part, the fact remains that from the early 2000’s up until now Australian films have been in production. Baz Luhrmann’s 2008 film Australia, starring numerous homegrown stars and depicting issues of European colonisation as well as life in the outback, is the third highest grossing Australian film of all time, demonstrating that if overseas audiences may not like all we have to offer, they are at least interested in our country.

The major question to ask is; what’s next? As we fully embrace the period of streaming services, where Hollywood films are even more readily available in the long lists of choices on Netflix, how will Australia adapt? In conjunction with Gough Whitlam’s 1975 Australian Film Commission, the Australian Film, Television and Radio School (AFTRS) opened in August of 1975. Featuring state of the art equipment as well as having projection equipment donated by the Motion Picture Distributors Association, this school, along with others such as the Academy of Australian Film, Theatre and Television (AFTT) and the Sydney Film School, house much young talent eager to make marks in the Australian film industry.

In terms of funding, Screen Australia still stands as the most important and prolific in output. Therefore, the main issue facing Australian cinema is not funding nor lack of ambition, but competition with American film. Many Australian actors are eager to abandon their lives in Australia for a career in Hollywood, while many films shot in Australia do not touch on uniquely Australian themes, making them, to international audiences, American. Combine these issues with the American and British productions both past and present that have become available on streaming services and it is easy to understand why Australian cinema continues to slip through the cracks, unnoticed and unrecognised regardless of quality.

With the issues that plague the world, many write off cinema as unimportant. Especially in Australia, quite a lot of the population would argue funding is unimportant and unnecessary and that such large sums of money could be put to better use, perhaps another ugly stadium or a new bridge to bounce fireworks off. But one only has to briefly learn of the history of Australian cinema, from The Story Of The Kelly Gang through to Mad Max and The New Wave movement and into the modern era, to appreciate the impact these films have had on Australian culture both in terms of identity and in solidarity as a nation. Film helps us to realise that, as Indigenous screen icon David Gulpilil says, ”We are all one blood. No matter where we are from, we are all one blood, the same”.

Subscribe to FIB’s Weekly Alchemy Report for your weekly dose of music, fashion and pop culture news!