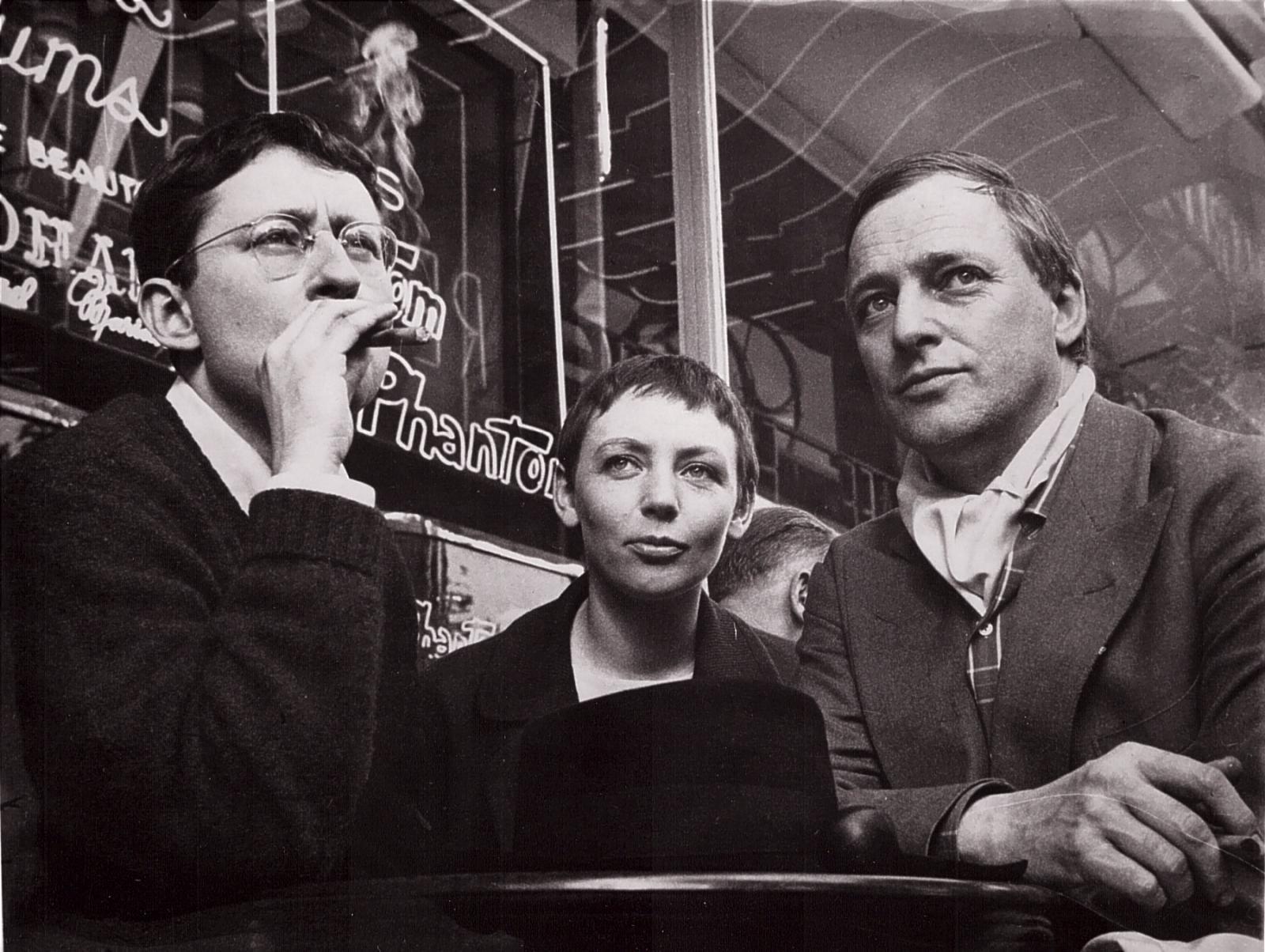

Founder of the Situationist International, Guy Debord created challenging and confronting films in line with his ultra left-wing politics and his heavily politicised views on art and cinema.

“All that was once lived has moved into representation.” French author and founder of the Situationist International wrote this line in his 1967 work ‘The Society Of The Spectacle’, which he would later adapt into a film. The statement sums up his attitude towards the world that he represented in both his written and cinematic works; a critique of the laziness of late capitalist society and the lethargy it evoked in the collective broader consciousness.

After a youth of vandalism and misbehaviour, Debord joined a group called The Letterist International when he was only 18. The group was run by a Romanian poet and artist called Isidore Isou, who established its principles in Paris during the 1940’s. Focusing on the use of symbols and letters, the artistic output of the group is fairly baffling 80 years later. However, Isou considered his written work done by 1950, and moved on to applying his artistic theories to film. With youthful ambition he announced in voiceover during his first film, “I announce the destruction of the cinema, the first apocalyptic sign of disjunction, of rupture, of this corpulent and bloated organisation which calls itself film.”

Letterist filmmaking focused largely on the film stock itself, with filmmakers scratching images into the stock or painting over it. Furthermore, many of the films abandoned images all together, or stole from other films. The screenings were made into live performances and debates, with the filmmakers confronting the audience and cajoling them into discussion. While Debord was with the group, he created a film called Howlings for Sade. The film features no images, only a white screen when the narrator quotes from written works, and a black screen when there is silence. Gaps between narration become increasingly longer until finally the film ends with a full 24 minutes of silence and darkness.

Howlings for Sade premiered in Paris in June of 1952, and was stopped after twenty minutes when the audience started to walk out or expressed their discontent. This, of course, was the kind of reaction that would have delighted Debord; immediate, hostile and intense.

Debord, as the new head of the Letterist International by 1957, met with the International Movement For An Imaginative Bauhaus and the London Psychogeographical Association in Italy to found a new group. This group, with Debord as their leader, were to be called the Situationist International, and would have an immense impact on art, life and politics over the next twenty years and through to today.

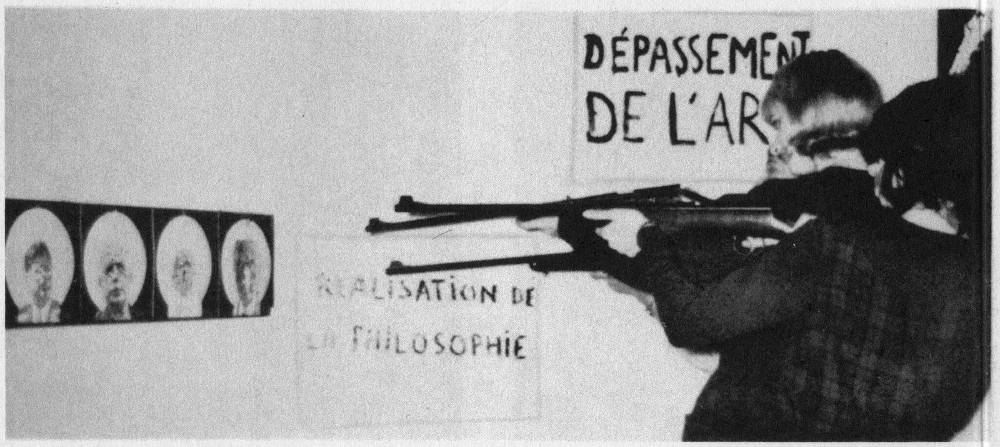

The Situationist International focused on the artistic world at their inception, and was composed mainly of revolutionary artists and writers. They caused havoc in the art world, disrupting gallery exhibitions, dropping pamphlets and getting arrested on a regular basis. They would also create reproductions of famous and expensive works in order to drop the value of the original. Most importantly, however, was that Debord never stopped writing theoretical treatises on the meaning behind their actions.

Following Debord’s decision to expel many of the more artistically driven members of the group in the 1960’s, the Situationist International turned their focus to politics. This decade saw a number of works and treatises criticising capitalist society, taking influence from Communist political thinker and author Karl Marx. Debord’s 1967 book, The Society of The Spectacle, summed up his views in concise and fragmentary prose. Debord believed society was kept under lock and key through our reception of information, history and art through constructed ‘spectacles’, as opposed to ever experiencing anything for ourselves. It was this book that contributed to the uprising in France in May 1968, with many protestors penning slogans and billboards using quotes from the work.

As a logical progression of his ideas on the ‘spectacle’, Debord turned his attention back to filmmaking after disbanding the Situationist International in 1972. Despite creating some short films during his time with group, it was his adaptation of his most famous work in 1973 for which he is remembered. The Society Of The Spectacle was his first feature-length film, and utilised most of his artistic ideas and practices to deliver a critique of both mass marketing and individual alienation in a capitalist society. The film is a compilation of footage from other popular films such as The Battleship Potemkin and For Whom The Bell Tolls with footage of historical events such the Spanish Civil War and the May 1968 riots as well as still photographs and glossy magazine ads. Debord reads from his own and others political works in voiceover or uses intertitles, demonstrating his détournement technique in which the artist hijacks and misquotes another work.

Because of the negative press over this film, as well as being offended at his incrimination in the murder of his producer, Debord withdrew this and other films, only agreeing to re-release them after his death. His last film, His Art And His Times, was unreleased, and was largely autobiographical in nature summing up Debord’s views on life, art and politics. Many consider the films a sort of suicide note, as Debord took his own life in November of 1994.

Though largely forgotten today, Debord’s films stand as visual testaments of his unique and scintillating attitude towards life and society. Inspiring in their uniqueness and just as violently energetic and boundary pushing as his written works, Debord’s cinematic output, while not prolific, certainly stands as one of the most fascinating collections in a time of revolution, revolt and poetry.

Subscribe to FIB’s Weekly Alchemy Report for your weekly dose of music, fashion and pop culture news!