First Nations fashion and streetwear is on the rise with an influx of new, developing firms. Following years of underrepresentation, First Nations designers are creating fresh business opportunities in Australia’s fashion sector.

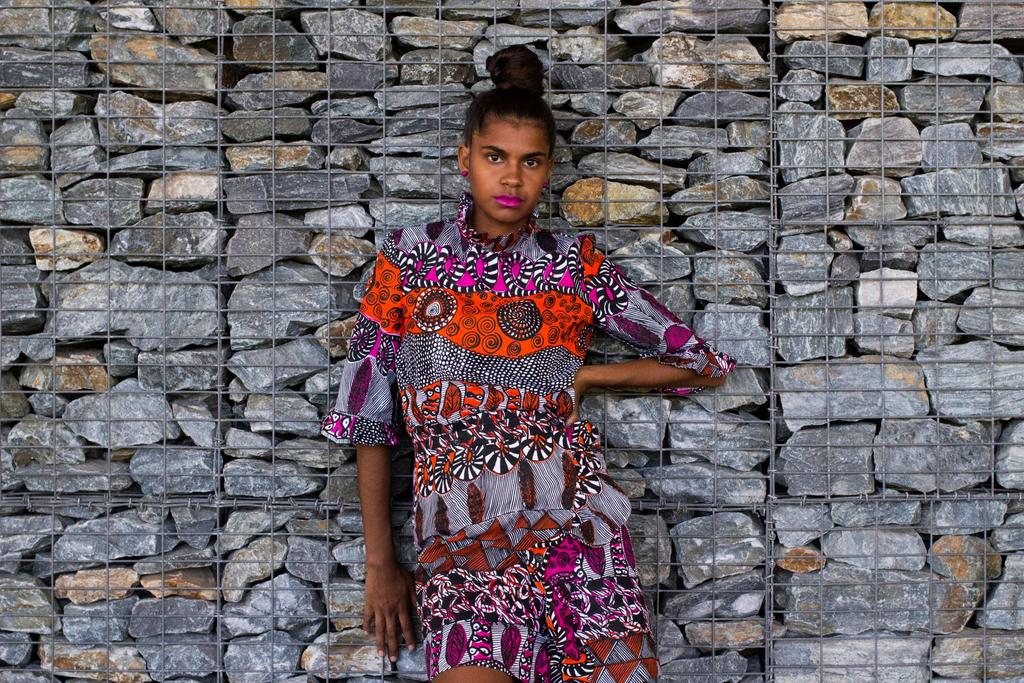

Afterpay Australian Fashion Week in 2021 is a reflection of the vast, boundary-pushing skill of local First Nations designers.

From Grace Lillian Lee’s psychedelic designs to Ngali’s silk-printed shapes, there’s a new wave of Australian designers emerging. These individuals hail from across Australia, including remote areas of rural Queensland, the Northern Territory, and country Victoria.

First Nations artists and designers are redefining what Australian fashion looks like, culminating in an expansive and innovative range of designs. Experts in sustainable apparel, traditional crafts such as painting, dyeing, and weaving have been passed down through generations.

First Nations designers are redefining what it means to produce an Australian-made item, blending mainstream trends with a sense of home.

These emerging designers pour their culture into hoodies, graphic tees, and more. The modern landscape of First Nation fashion is diverse, ranging from rural villages and art centres to young designers working in city centres. The resulting designs pay homage to both their ancestors and their homeland.

A Diverse Scope

The rising popularity of First Peoples runways proves that First Nations fashion is quickly becoming a permanent fixture. Increasingly, First Nations people are shaping fashion design at every level.

Scott McCartney, CEO of Kinaway Chamber of Commerce Victoria, recalls one show that got him thinking about the future. The proud Wotjobaluk man explains to Creative Victoria,

“It was a fashion show, sold as indigenous, but most of the designers were actually non-aboriginal,”

he recalls.

“It set off alarm bells. The common (business) model was a non-aboriginal designer acquiring rights to aboriginal artwork, then applying it to their garments…”

The Black Lives Matter movement in the United States and Australia recently taught buyers to support African American and Indigenous-owned businesses.

Now, the future leans towards more ethical production methods and inclusive expressions of style. First Nations fashion is capturing the imagination of the industry – and it’s safe to assume it isn’t a passing fad.

A strong highlight of the First Nations design process is its low impact, sustainable practices. Plant-based dyes and fabrics from locally grown and sourced textiles are two of the style’s mainstays.

An emphasis on mainstream designers is rebuked by First Nations fashion. It’s built on broad community engagement. It questions conventional concepts of the fashion designer as solo, instead drawing on the stories and experiences of a greater culture. The employment of garments to enhance awareness of First Nations peoples and their history, lessons, and hardships is a significant recurring thread.

Illuminating Pathways

At a Magpie Goose pop-up shop in Sydney’s Redfern, colourful clothing fills the racks. The label is a profit-for-purpose/social organisation that assists Aboriginal people living in outback Australia by illuminating options and pathways.

The clothing’s fabric is meticulously screen-printed on yards of fabric at locations such as large, airy sheds on the Tiwi Islands. Artist Mario Munkara explains the design elements of the ceremonial prints. He tells the ABC that it represents various styles of body painting and scarification used during funeral ceremonies.

“They used to have the scars around their chests, and the ladies used to have it on their breasts and shoulder,” he says.

The fabric, telling a very old cultural story, transforms into vibrant clothing for the First Nations label.

The pieces are all created by local artisans. Sphinx, an Ethical Clothing Australia-accredited manufacturer, goes on to manufacture the Magpie Goose garments in Australia.

Each purchase comes with a card explaining the story behind the print and the Aboriginal artist who created it. The brand’s managing director, Troy Casey, a proud Aboriginal man from Kamilaroi Country, has big ambitions. He Tells the ABC, “It’d be great for this to be an international brand, and iconic Australian brand.”

Until March, the social enterprise behind these clothes had been run by two non-Indigenous women. Now, Magpie Goose has transitioned to Indigenous ownership.

This change comes at a time where brands in Australia are seeing a rise in consumer awareness about ownership. Pull Up for Change founder Sharon Chuter tells the ABC,

“You cannot be preaching to other people about racism if your board is whiter than snow”.

Anti-exploitation

Jarin Baigent is the brains behind TradingBlak’s newest outlet, Jarin Street. Baigent says she’s inspired by ongoing tales of legitimate First Nations artists being exploited by non-Indigenous owned businesses.

She tells SBS,

“Without our culture and our art there was no product, there was no business. So, really, we were the most important part of those business models. And to be honest I was just sick of us not being in control in the driver’s seat in those relationships”.

Located in the heart of one of Sydney’s most popular retail malls, the Warringah Westfield boutique bursts with vibrant colours. The store only stocks Aboriginal owned and designed products.

Baigent is also the Managing Director of TradingBlak. Per the website, it’s “a platform which promotes transparency and ethical practices among businesses trading in Aboriginal culture to combat ‘exploitative’ operators”.

Baigent explains,

“TradingBLAK is a space for Aboriginal business to stand firm as leaders in a space rightfully ours.”

Bagent drives herself with a desire to see more TradingBlak companies in mainstream areas. The fitness wear designer encourages First Nations entrepreneurs to venture into trading authentic goods and services. Not only does the space sell grassroots brands, but it’s also known as a meeting area for youths and young people.

Inclusive Principles

First Nations apparel is more than just a fashion statement. It also emphasises connection and community. Indigenous pride sits at the heart of every business, a celebration of First Nations Australian tradition and heritage.

Kristy Dickinson is the founder of Indigenous Australian business Haus of Dizzy. The Wiradjuri designer recalls being bullied as a child for being Aboriginal. These days, Dickinson is self-dubbed as the “queen of bling”.

She tells the the ABC,

“I just wish I could go back and shake that little girl and go, ‘Be proud of who you are and make your mum proud. Don’t ever be ashamed of who you are.’”

Dickinson expresses her voice via the artistic medium of jewellery. Her creations, both acrylic and fine metal-crafted, brandish a number of meaningful phrases.

It’s a stylised form of statement-making to honour the First Nations people. This bright, on-trend jewellery embraces Indigenous culture, giving wearers a sense of confidence and joy.

On the streets of Newtown, West End, and Fitzroy, at the demonstration, at the club, on the red carpet. This jewellery is activism meets art.

Indigenous Pride

In the designer’s mind, there’s plenty of room for treaty, trans pride flags, 90s hip-hop, dinosaurs, teen fashion dolls and smashing the patriarchy.

Dickinson tells The Guardian, “My friends always say Haus of Dizzy is just Kristy spewed up in earring form”. Her slogan pieces rep environmental campaigns (“Stop Adani”), feminism (“The Future is Intersectional”), gay rights (“Love is Love”) and sweary mantras (“Fancy as Fuck”).

Her Indigenous Pride range includes “Faboriginal” hoops and “Deadly” necklaces.

“I just want to give pride to my people,” Dickinson says. “But in a cool, shiny way.”

Each Haus of Dizzy sculpture is laser-cut, with hand painting and construction via the company’s studio in Fitzroy, Melbourne/Naarm. The jewellery often displays potent political and social statements.

Haus of Dizzy also continues to promote, support, and contribute to Indigenous culture. This happens thru behind-the-scenes fundraising and collaboration activities.

Whether it’s the neon “Cool Aunty” earrings, sparkly Aboriginal flag hairpins, glossy Bamboo Hoops, Sunflowers, Spaceships, Lightning Bolts or other radiant designs, Haus of Dizzy products facilitate conversations and attract attention for the right reasons.

Check out Kristy Dickinson’s interview with “Faces of Small Business” below:

Subscribe to FIB’s Weekly Breaking News Report for your weekly dose of music, fashion and pop culture news!